6, 7 and 8 February

Tuesday 6th

“Everybody knew,” he says in a disgusted whisper about Harvey Weinstein. “Everybody knew.”

That’s actor Tim Robbins in the Times. The same can be said about the case of James Levine: here in New York, everyone interested in serious music “knew” about the great conductor’s irregular sex life. Well, of course there were only a few people who actually knew — relative to the overall population, anyway. But most people had heard tell. And what happens, when everybody knows, is that nobody does anything. Offenses already committed go unpunished, while further offenses go unstopped.

Something beyond knowing is required. In the old days, that something was religious sanctions, often backed up by the power of law. We don’t want to go back to that. We don’t want to give anyone the power to forbid Harvey Weinstein to do things, because that power necessarily includes the power to decide what to forbid.

Back in the days when religious officials had secular clout, there was also a social institution that protected women from the Weinsteins of the world. This was called respectability, and, like religious sanctions, it had many harsh side effects. In the name of protecting women, women punished women, whenever women disregarded respectable scruples. Nineteenth-century novels are full of the heartbreaking tales of fallen women, whose shame so often seems to lead, however mysteriously, to poverty and illness, and ultimately to death. A few women braved this treatment. George Eliot (née Mary Ann Evans) lived openly with a married man for years, and although the men of literary London were not ashamed to be seen at her receptions, their wives stayed away. But then, she was a very famous and successful novelist. Few women had her resources. Outside metropolitan areas, women deemed to be not respectable risked being hounded out of town. We don’t want to go back to that, either.

My wife, Kathleen, a lawyer in her mid-sixties, has never attended a meeting in a man’s hotel room. She doesn’t believe that she has ever been asked to do so, but she knows that she would have refused, or, even more likely, headed off an invitation before it was made. She says that she cannot understand why a woman would do such a thing, but then she is a graduate of Brearley, Smith, and, did I mention, a lawyer. Let’s throw in the Convent of the Sacred Heart while we’re at it: everything about Kathleen’s upbringing instilled an almost militant self-respect, a powerful deterrent to unwanted advances. Like George Eliot, she has had unusual resources. What about ordinary girls? What about girls who are naïve, or starstruck, or very ambitious, girls whose judgment, for whatever reason, is a bit faulty? What about girls who are lonely or needy, whose imperfections may make them somewhat complicit in abuses of power by those who employ them? We appear to have arrived at a new unwillingness to dismiss the bad things that happen to these girls as just desserts or business as usual. That’s great. But how do we prevent them in the first place?

And how about men? It seems to me to be absolutely typical of Anglophone culture that here’s the deal: boys will be boys, but if you get caught, we’re gonna shoot you. Viva Las Vegas! Play your cards right, you can grab at will. Miss a trick, and you lose your job, possibly forever. So far, the #MeToo conversation has not sprouted a #NotI correlative.

***

As usual, liberalism is at the heart of the problem. (Cue mordant laughter.) Although the Founders piously believed that separating Church and State would allow churches to flourish, in mutual toleration, it wound up killing them, because a tolerant church is not a religious church. That’s to say that a religion that doesn’t frighten its observers into compliance loses observers, and a church that is complacent about the noncompliant folks who attend the church across the street isn’t very frightening. The Fear of God is something that, in the secular West, only observant Jews appear to have internalized, and even in that case, life in self-segregating neighborhoods entails frightening social pressures.

Most of us don’t want to go back to that. We’re happy with the liberal convention: in exchange for observing the public laws of society, we are granted the quiet enjoyment of our privacy. The problem with this social contract is that it is still rooted in the vision of a world of benign men who are the only parties to it — the dream of Enlightenment Europe. Women have fought successfully for participatory rights, but only to find that arrangements made by roughly equal males do not easily accommodate peculiarly female difficulties. Liberal society has always presupposed a membership of men who can take care of themselves, so that it doesn’t have to. This is why liberal society has been so bad at protecting the weak, aiding the poor, and, most notoriously, freeing the enslaved.

I want to pause here to address the widespread misconception that protecting the weak and aiding the poor are “liberal values.” They are not. That is why liberals have had to pass specific laws to deal with egregious social problems; left to itself, liberal society was prepared to go on living with them. As indeed it did, even after “liberal” laws were enacted. As we are finally openly admitting, it was one thing to enact laws that granted equal access to voting booths and decent schools, and other thing to enforce them. The liberal solution to social problems is to pass a law and hope for the best. Anything more invasive would disturb that quiet enjoyment — which in awful cases involve wife-beating, and in worse ones, children locked up in basements.

What would a liberal society look like of women undertook to re-imagine it?

***

Wednesday 7th

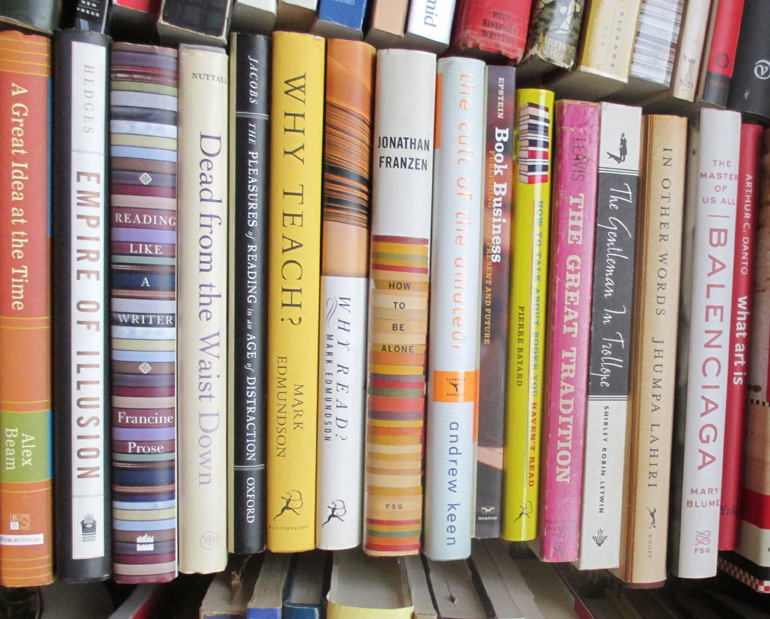

It’s time to get back to work on my writing project, an intellectual memoir in which I try to account for the way I think. My first draft, while readable enough, was encrusted with a great deal of biographical material that wasn’t relevant to my thinking life. That this material was also incomplete and even evasive annoyed one reader.

I’m having trouble deciding what do to with this second paragraph. Should it touch on the inspiration that I’m getting from Elizabeth David’s writing about food? From re-reading two biographies of David, both of which stress her proud and insistent privacy, which rejected all attempts to elicit information that she did not deem suitable for publication? The biographies are stuffed with such information, much of it unflattering. The result, however, is that the character of Elizabeth David that emerges from the pages of her own work seems to be the real, the important woman, while the subject of the biographies is an accident of human frailty. My own life story is full of mortifying incident. Tall, glib, and headstrong, I was a grossly presumptuous young man, usually unconscious of my manipulations, but inexcusably so. I ought to have known better. The only interesting thing about my catalogue of errors is that it seems to have come to an end, perhaps for no better reason than that I outgrew it. Or, perhaps, I finally figured out what I was trying to make of my life, and stopped thrashing around in dead ends.

In the alternative, my second paragraph might have jumped ahead to what’s on my mind today, which is three aspects of my intellect that seem to have been firmly in place by the time I got to college.

First, I regarded “academic success” as just that, a notion that must be buffered with scare quotes. It did not seem to me that, sciences aside (and I was never interested in science except as a subject of intellectual inquiry with a fascinating history), anybody was the wiser for having performed well on an examination. At boarding school, examinations dropped out of the picture during my senior year, in my favorite subject, English History. Tests were replaced by “papers,” an apparently unending stream of essays of six or seven pages in which I analyzed and discussed historical issues as well as I could. These papers were not about questions and answers but about me, about how well I not only understood something but could write about it persuasively. All that I remember of that year, at least so far as schoolwork was concerned, is typing those papers, week after week.

It was obvious to me that writing essays was the heart and soul of an education. It was hard work, because, probably as a consequence of being headstrong, I always seemed to know too much about some things and not enough about others. But there was tremendous satisfaction in typing up what I’d learned in my own words.

It was also obvious that there was no connection between the work that I was putting into my papers and the practical matter of getting a job some day, unless I wanted to teach English History, which wasn’t very likely, regardless of my own inclinations, because overall “academic success” eluded me. Studying for tests was inherently pointless and boring. It wasn’t always necessary for me, but when it was, the results were disappointing.

I outgrew this fussiness later, when, seven years after graduating from Notre Dame, I went back as a law student. I studied for tests; I studied hard. And even though the examinations all took the form of essay questions, I did not necessarily do very well, because by now I had a somewhat idiosyncratic prose style, with a Jamesian distaste for straightforward writing. Nevertheless, I got through it, and subsequently passed the New York State bar exam. But although I did learn to buckle down to the weary work of of evaluating proximate causes, my conviction that there was something bogus about American education was as firm as ever. American education was not about education, but about staffing a meritocracy.

Second, I was never a “person of faith.” I never believed in God. Walking down the aisle in my white First Communion suit, I worried about being struck down by lightning, my fraudulence exposed. But even my faith in a god who would punish me for not believing in him was wobbly. Looking back from early middle age, I thought I must have been a materialist from the beginning, incapable of believing in anything I couldn’t see or touch, but now that I’m an old man I have to confess that I believe, and have always believed, in a lot of things for which there is little or no positive evidence. I believe that a society in which people treat each other reasonably well is a functional and reliable as well a happy society (or happy enough). I believe that learning is important. But I can’t even imagine believing in a supreme being of some kind. Which is to say that, if it could be somehow demonstrated to me that there is such a being, I would still dismiss the news as meaningless, because I cannot comprehend such immensity.

As a consequence, I believed that human beings are the most intelligent and capable beings in the known universe. Existence must be its own significance.

Third, I was sure that nobody knew what was going on. I am about to try to explain what I meant, just now, by saying that existence must be its own significance. What was going on, really going on, way back in, say, 1960, was an almost but not quite chaotic cascade of the consequences of the great revolutions in human life that were launched in Western Europe at the end of the Eighteenth Century. As Zhou Enlai was said to have said, it was still much too early to assess the implications of these upheavals. The meaning of life, which is to say the meaning of my life in a Westchester suburb during the Eisenhower Administrations, was nothing but the unfolding of contingencies triggered less than two hundred years earlier. Now, I didn’t know at the time that this was what was really going on. I knew that I didn’t know what was going on, either. But I was sure that people were wrong to think, as so many people seemed to do, that the world had been recreated in 1945, that the wonders of technology and the horrors of the Cold War were unprecedented novelties. Now I understand why they thought this: what adult wouldn’t have wanted to forget everything that had happened since — pick a date — 1848? 1860? 1870? 1914? 1929? 1933?

How, you may ask, can a little boy of nine or ten, no matter how smart or clever, see the emperor’s new clothes for what they are? As the Sixties would demonstrate, lots of kids had noticed the embarrassing nakedness. I never claimed to be unique.

***

Thursday 8th

It took a little while for me to order Justin Spring’s new book, The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and the Birth of a New Gastronomy; eventually, I bought it for comic relief — which it amply provided. The comedy is intentional, I hasten to say, and confined largely to two chapters, one of which I’ve re-read with great glee; but more about that in a minute. I have been, as I’ve reported, reading about Elizabeth David, and it was getting to be too intense, as was reading her books themselves. I mentioned yesterday the connection that I feel between her story and mine (which has nothing to do with content or achievement); this only made the immersion more suffocating. Justin Spring provided marvelous respite. I’m not sure that this amounts to a recommendation, because reading Gourmands’ Way deepened many of the misgivings that I’d had about it before reading it. Nevertheless, it was a great treat.

My question going in was what, really, Spring’s six food writers had in common. Not even food, really, for Alexis Lichine, one of the three outliers in my view, wrote exclusively about wine, and he would have written more if he hadn’t been so busy marketing and selling it. The other two oddballs are A J Liebling, who doesn’t seem to have boiled an egg in his life, and Alice B Toklas, whose famous cookbook is a notoriously unreliable literary relic, written in conditions of dire financial distress. This leaves three figures who do form a group of sorts, Julia Child, Richard Olney, and MFK Fisher. But Fisher really doesn’t belong in such company; she has more in common, as a writer, with Toklas. Only Child and Olney can be regarded as developers of a “New Gastronomy,” although even that seems wrong, since both were students of traditional fare. The novelty, of course, was their persuading Americans to give it a try.

And this is where the “Americans in Paris” theme goes flat. Child and Olney were part of a larger Anglophone movement to respond to some social changes, most notably the disappearance of household servants, while resisting others, primarily the industrialization of food. And nobody expressed this movement’s mission better than the ultra-English Elizabeth David.

Good food is always trouble….Even more than long hours in the kitchen, fine meals require ingenious organization and experience which is a pleasure to acquire.

Lisa Chaney, who quotes this remark on page 264 of Elizabeth David, does not provide a source, but I’ll be on the lookout for it. In her television shows, Julia Child liked to assert that what she was doing was really pretty simple, but of course it would be simple only to someone who had done what she was doing — a lot. The idea that good food can be tossed off in ten minutes is irresistible, but it’s at best a gross deception, rather as it would be to say that it take only a little over a minute to play Chopin’s “Minute” Waltz. Chaney italicizes the last phrase in David’s comment, which is a pleasure to acquire. If acquiring experience in the kitchen is not a pleasure, then cooking is not for you. What surprised almost everybody during the Fifties and early Sixties was that the people who found it a pleasure constituted a substantial market.

In many ways, David spearheaded the movement, and was regarded, by Child and Olney along with everybody else, as having done so. And when we look at how and why David spearheaded it, we encounter a third element of change: travel. There had always been journalism for rich people looking for good restaurants, but David was a more serious, older kind of traveler. She actually lived on the shores of the Mediterranean, spending most of World War II in Alexandria and Cairo. She wrote her first book, A Book of Mediterranean Food, in a kind of despair. It was partly the same despair that motivated Alice Toklas (money), but much more than that it was revolting against the deprivations of food-rationed postwar Britain. David famously wrote that merely writing words like “apricot” provided “assuagement.” Child and Olney also did more than just tour Paris and Provence. They lived there, Child for a time and Olney for most of his life. A great part of the appeal of following the recipes of these writers was and is to feed either memories of visits past or dreams of visits to come — visits that included or would include a kitchen in a foreign land.

Then — to return to Gourmands’ Way — there are the fascinating people whom Spring leaves on the sidelines, like Dione Lucas and “Philippe of the Waldorf,” the latter an extraordinary operator who controlled a $2.5 million food and wine budget (in the Forties!) and who was arrested for extortion and tax evasion — a most interesting character. There’s Philippe’s sometime wife, the extraordinary Poppy Cannon, a major perpetrator of processed food. There are Craig Claiborne and Pierre Franey. There’s James Beard, who did for American food what Spring’s crowd did for French. There’s Simone Beck, without whom Child’s career would not have launched. These characters rumble beneath Spring’s narrative like lumps under a carpet. I wanted them in the big picture. Needless to say, Elizabeth David languishes on the sidelines as well.

Spring aims for balance, but a bias very much in favor of Richard Olney and slightly against Julia Child is evident. Olney gets the lion’s share of the narrative, creating a suspicion that Spring felt that he didn’t have enough for a stand-alone book, or that, even if he had, Olney lacked the star power to carry one. There is something strangely muted and humorless, something almost overly decent, really, about Olney; his devotion to his siblings was, to me at least, unusual. Only an American could have had his career, which combined a refined palate and knowledge of food and wine, the worldly sophistication that goes with being a painter in Paris, and a knack for building construction and renovation. While many French men combine two of these qualities, the French educational process more or less assures that few will have all three.

The fun chapter is the fourteenth, “MFK Fisher and The Cooking of Provincial France.” I am not going to quote more than a single quip. When this Time-Life production was translated into French, in 1969, it was annotated by a very conservative man who larded it with footnotes contradicting Fisher’s many mistakes and misjudgments. The book was published before anyone in New York vetted the commentary, leading to great embarrassment. Times writer John Hess wrote that The Cooking of Provincial France was “self-roasting.” Spring’s account of the whole fiasco, which sprang from the buzz that accompanied the rediscovery of Fisher’s books and the associated assumption that she knew what she was talking about, is hugely entertaining. Also as much fun is the chapter about Alice Toklas second cookbook, in which Poppy Cannon provided breezy alternatives to Toklas’s laborious recipes, right on the same page.

On page 444 of her biography, Lisa Chaney wonders why Elizabeth David never met MFK Fisher on one of the many visits that she paid to San Francisco in her later years. On page 319 of her biography, Artemis Cooper ventures an answer. But once you’ve read Justin Spring, you’ll see that it’s ridiculous even to ask the question.

Bon week-end à tous!