Gotham Diary:

Do Not Disturb!

14 November 2011

Monday, November 14th, 2011

A few hours’ of imprudent hankie-sharing with runny-nosed Will, on Friday, obliged me to swallow a dose of NyQuil last night, enabling me to regret my lack of backbone this morning. Worse, aside from a few hours spent on housework, on Saturday, I did absolutely nothing this weekend but read Alan Hollinghurst’s very beautiful book, The Stranger’s Child; so, not only am I spineless but I find myself swaddled in a dream of that green and sceptered isle. Â

***

I’ve read two frowning reviews of The Stranger’s Child, by James Wood and Daniel Mendelsohn. Both reviewers, it seems to me, want Alan Hollinghurst to do something that he’s clearly, on the evidence of the novel that he has actually written, not interested in doing. To be sure, they come to the book from opposite perspectives. To Wood, who is English but who works in the United States, the novel flirts with sentimental preciosity; it is too prettily English. To Mendelsohn, an American, the novel lacks a sympathetic core; what he doesn’t get is precisely what Wood’s afraid of: that The Stranger’s Child is about England. But the two critics unite is in a demand that the novel take a moral position on something, anything. Wood, complaining about what, to him, are stylistic curlicues:

These flecks of aspic are scarcely heinous, but cumulatively they suggest an overindulgent hospitality toward the material. Hollinghurst seems too ready to perpetuate a fond English elegy that he should, instead, be scrutinizing.

Among Mendelssohn’s numerous expressions of discontent, here’s the baldest:

You have to wonder what is being critiqued in the new book.

Do you? I thought that scrutiny and critique were critics’ tools, not novelists’. The critical habit of finding social criticism in novels is as easy to explain as the connection between the generosity of the Marshall Plan and trumped-up fears of communism in postwar America: it justifies the reading of fiction/the spending of millions. That’s to say that it appeases an anxiety about the “uselessness” of fiction — and of art generally.

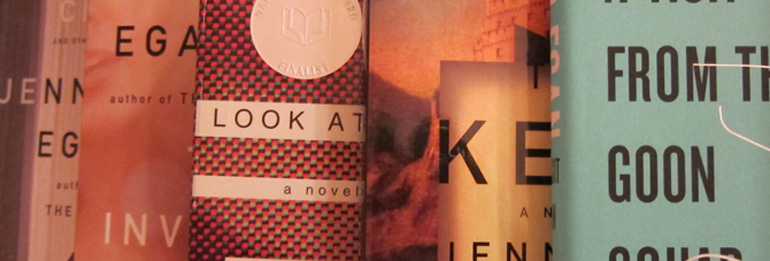

But what Hollinghurst wants to do, it seems to me, is to tell a story, a particular kind of story, possibly a new kind of story — the only other example of such a story that I can think of is Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad. It is the kind of story in which a very great deal of material is omitted. One of the characters in The Stranger’s Child, Jennifer Ralph, has an interesting parentage; her father was the child of Daphne Sawle Valance Ralph (the central character if not — and she definitely is not — the novel’s protagonist). But who was his father? That’s a question that the book chews over for moments at a time. But the man himself, this child of dubious provenance, this father of a woman whom we meet as a girl and then as an Oxford don — this man never has a name. All we know about him is that he was “in rubber” in colonial Malaysia. I don’t regard Jenny’s father’s namelessness as a negligence. I think that Hollinghurst wants us to note it, and to take it as a reminder that every story involves the back ends of countless other stories. His story has lots of such holes.

The point of a novel such as The Stranger’s Child is to work a novel out of a story full of holes; to put it more “artistically,” we might speak of a narrative that weaves content with lacuna. I don’t want to carry this idea too far; the point is never that what’s left out is as or more important than what’s put in. In Egan’s book as well as Hollinghurst’s, though, the reader is unavoidably aware of making the calculations that impose coherence on the narrative. Egan’s calculations are a little more demanding than Hollinghurst’s, possibly because her book is frankly prospective, whereas The Stranger’s Child is “all about” the past. But the work is always pleasant and intriguing, never onerous. There is nothing new, of course, about readers’ completing stories in their minds; our minds flesh out the verbal content of every sentence that we hear. This new kind of novel that Egan and Hollinghurst have explored simply makes us aware of something that we do all the time. The very old-fashioned term for it is “leaving something to the imagination.” It’s what popular bad writers make their fortunes by avoiding.

***

It seems impossible — I must be mistaken — but I clearly remember a day, in the summer of 1977, when my father and I were driven from London to Stratford-on-Avon. This was a sentimental journey for my father; he had visited what he called “Shakespeare Country” several times with my mother, who had just died, and even though I never heard either of my parents so much as speak the name of any of Shakespeare’s works, they liked the countryside. (A similar fondness for “Sound of Music Country” remained stoutly disconnected from any interest in Mozart.) I know that you can make a day trip out of Stratford, but can you also see Blenheim, walk around Oxford, and have a leisurely lunch at a country hotel not too far from Birmingham? Yes, if you were traveling with my father, you could.

That drive is my total experience of the English countryside. It differs at no point from anything that I’ve seen in the movies. (Toss-up question: have more films been shot in Manhattan or the Home Counties?) And when I read about the English countryside, even though I can’t tell a spinney from a combe, I feel that I’m on very familiar ground. (The ground that I actually grew up on, which is the same here in Manhattan, especially at the north end of the island, as it is in Westchester County, is rather more exotic, a great deal rockier, beneath all the roads and buildings, and wilder.) This is not just because I know what England looks like, however; it’s because I’ve spent so much of my life in the heads of characters who’ve spent so much of their lives walking around in it. From Forster and Woolf to Ishiguro and McEwan, I’ve walked hundreds of English miles.

The Stranger’s Child is certainly a novel of the countryside. London is a grimmish offtstage anti-presence until very near the end of the book, by which time the city has swallowed up the village in which the story begins. London may be about pomp, but it’s the country that speaks of English power.

The High Ground was an immense lawn beyond the formal gardens, from which, though the climb to it seemed slight, you got “a remarkable view of nothing,” as Dudley put it: the house itself, of course, and the slowly dropping expense of farmland towards the villages of Bampton and Brize Norton. It was an easy uncalculating view, with no undue excitement, small woods of beech and poplar greening up across the pasture-land. Somewhere a few miles off flowed the Thames, already wideish and winding, though from here you would never have guessed it. Today the High Ground was being mown, the first time of the year, the donkey in its queer rubber overshoes pulling the clattering mower, steered from behind by one of the men [it’s 1926], who took off his cap to them as he approached. Really you didn’t mow at weekends, but Dudley had ordered it, doubtless so as to annoy his guests. George and Madeleine were strolling on the far side, avoiding the mowing, heads down in talk, perhaps enjoying themselves intheir own way.

This passage serves very well as a skeleton-key to Hollinghurst’s cabinet of wonders: England is very beautiful precisely because of ownership arrangements that, from time to time (if not more often) throw up monsters like Dudley. And on flows the Thames, unseen. Â