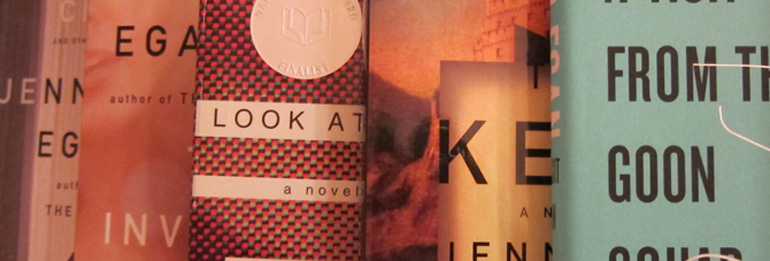

Reading Jennifer Egan:

Wrong and Bad and Exactly Right

10 February 2011

“It was wrong and bad and exactly right.” This sentence appears in “Sacred Heart,” the second story in Jennifer Egan’s collection, Emerald City — also her first book. The narrator, Sarah, a fourteen year-old schoolgirl, is on the verge of befriending an oddly attractive classmate named Amanda.

She wore silver bracelets embedded with chunks of turquoise, and would cross her legs and stare into space in a way that suggested she lived a dark and troubled life. We were the same, I thought, though Amanda didn’t know it.

Sarah comes upon Amanda in the girls’ lavatory one day. Amanda is trying to cut herself, but she doesn’t have anything sharp enough. Sarah offers a pin that she is wearing. the pin was a gift from her step-father, whom she dislikes, but without real conviction, “as if my not like him had been decided beforehand by somebody else, and I were following orders.”Â

The offer of the pin is not enough; Amanda asks Sarah to do the cutting. Convinced that Amanda will never be her friend otherwise, Sarah overcomes her revulsion and complies. But Amanda does not quite become her friend. If she and Sarah are “the same,” then Amanda still doesn’t know it. When Sarah confesses that, if she had only one wish in the world, it would be to be Amanda, Amanda pulls away with incredulous laughter: she’s not even going to try to understand Sarah.Â

Later, Amanda runs off with her brother (to Hawaii, it turns out), leaving Sarah in despair at having been left behind: her school now becomes the place that Amanda has rejected. This is a theme that runs through Egan’s fiction: home is the place that you leave because you have so literally outgrown it, like a shell that must be sloughed off, that it simply ceases to exist. What’s left is a dull but irritating simulacrum that must be escaped.Â

One night, Sarah cuts her arm deeply with a razor blade. It is something between an accident and a suicide;Â it’s as though she’s offering herself as a sacrifice to Jesus (whom she imagines Amanda’s brother to resemble). The ecstasy is too fast and frightening. She summons her stepfather, who rushes her to the hospital. They make peace. Later, she encounters Amanda, who is now selling shoes in a department store. After a brief, almost desultory conversation, Amanda walks Sarah to the door of the store and gives her a kiss. Sarah treasures the scent of Amanda, only gradually realizing that what she smells is herself.Â

You feel that Sarah has negotiated a tricky passage in her life, but you can’t be sure.

In Look at Me, the escapes are recursive. The principal character, Charlotte Swenson, leads a life of escapes that, finally, she escapes once and for all. A rough schematic of her career would have her escaping her childhood home, Rockford, Illinois, at the earliest possible moment, for a life of modelling in New York, where she is happily married for a few years only to find, on assignment in Paris, that she must escape that life. She continues to be a successful model, but she escapes New York at last, on an impromptu road trip with a mysterious foreigner whom she hardly knows. Their destination? Rockport! The foreigner wants to see the heartland. But the road trip turns into something that Charlotte has to escape — which she very nearly kills herself doing. After a long recuperation (and this is where the novel begins), Charlotte returns to New York to try to resurrect her career, but her reconstructed face is not what it was, and she winds up participating in a bizarre docu-drama about her own (failed) life. In the act of playing herself, Charlotte finally finds resolution — by selling her identity to an Internet outfit that has weirdly prefigures the social network.Â

The three other important characters, Charlotte Hauser, her uncle, “Moose” Metcalf,  and the mysterious foreigner, are also engaged in escapes. What is omitted is the reason, the cause, the emergency, the whatever-it-is that makes Egan’s characters believe that they must escape. But it would not be wrong to say that their maneuvers often begin with something that feels wrong and bad and exactly right.

Reading A Visit From the Goon Squad last year was a revelation, but it remains one that I don’t quite understand, and in a series of entries here I want to come to terms with that. I have read Look at Me and The Keep twice; I shall re-read Visit as I work on this project. I don’t mean to slight The Invisible Circus, Egan’s first novel; it’s a great read, not least because it contains the most sustained (but not prolonged) incidents of sexual surrender that I’ve encountered between the covers of a novel. But it did not leave me with the unsettling uncertainty with which I came to the end of the two middle novels, both of which are virtuoso performances as well as ripping yarns.Â