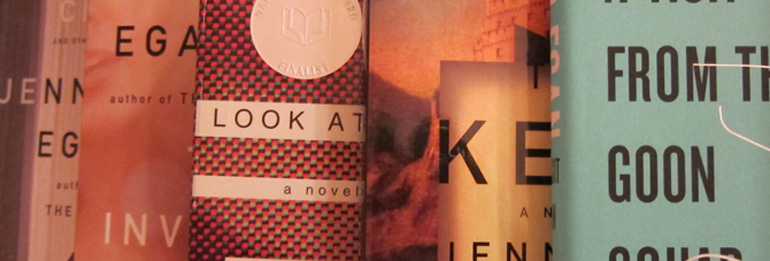

Reading Jennifer Egan:

Rapturous Images

14 March 2011

Since my last entry on A Visit From the Goon Squad, we’ve had the good news that the book has won the National Book Critics Circle award for its author. News of the award usually mention that the novel is “set in” or “about” the “music business,” a connection also announced by the drawing of a guitar’s headstock on the (American edition’s) dust jacket. “Music business” is, obviously, an unstable term; serious participation in any of the activities associated with one of those nouns generally precludes awareness of the other. But the sale of beauty, the commercialization of aesthetic experience, is a problem throughout Egan’s work. (In “Puerto Vallarta,” a story from Emerald City, the cheating father sells franchises to a lobster restaurant that uses “real butter.”) If this is a kind of prostitution, Egan’s businessmen are pimps who long for more than a percentage of the transaction. And if music — popular music — is the business, then what’s longed for includes the impossibility of youth regained.Â

“The Gold Cure,” Goon Squad‘s second chapter, belongs to Bennie Salazar, who, like Sasha from the first chapter, is one of the novel’s recurring characters. Now in his mid-forties, Bennie is afflicted by shames — powerfully unpleasant memories for which he may or may not have been actually responsible but which leave him feeling humiliated — as well as by a flagging libido. Bennie is a successful music producer; although he sold his label, Sow’s Ear, to a multinational oil company five years ago, he still runs the operation. But he can’t shake the conviction that the music that he is promoting is “bloodless.” The old songs that Bennie prefers to listen to are the ones that, in contrast, inspire “rapturous images of sixteen-year-old-ness” and remind him of his high-school band — a scene that we will visit, through other eyes, in the third chapter. The chapter title refers to Bennie’s costly faith in the efficacy of gold flakes, which he drops into his coffee; so far, however, the gold cure has failed to ignite his engines. Bennie is, in short, one of Egan’s trademark desperate characters. He may not want for funds or health or occupation, but without youth these boons mean little. Meaning is leaking out of Bennie’s life with a fairly audible hiss.Â

In “Found Objects,” Sasha and her date, Alex, had drinks at the Lassimo Hotel, which Sasha chose “out of habit; it was near Sow’s Ear Recods, where she’d worked for twelve years as Bennie Salazar’s assistant.” In “The Gold Cure,” Sasha is still Bennie’s assistant; what’s more, Egan throws us an anchor by which to date the chapter: five years have passed since 9/11. So we have moved at least a year or two before the “present” of the novel’s opening, but not too much more than that, because Sasha has been working for Bennie for a long time — so long that he no longer sees any part of her but her breasts, which serve as a “litmus test” of his randiness. Sasha’s ability to bear up under this wolfishness without embarrassing her boss is only the lesser half of her expertise; she also understands the running of his business better than he does. (As Bennie puts it, Sasha is always finding the things that he has misplaced.) At the end of the story, when Bennie collapses into a lustless longing for Sasha, she demurs: “We need each other.” Sasha and Bennie can be together only on the business side of the music business.Â

There is no sign in this sad scene of the personal damage that (as we saw in the previous chapter) goaded/will goad Sasha to steal things; we not only see Sasha from the outside but from Bennie’s sporadic and largely inattentive point of view, which allows her to become little more than what Bennie wants her to be: someone with whom he can feel the “safety and closeness” that he knew with his ex-wife, Stephanie, “before he’d let her down so many times she couldn’t stop being mad.” One might evince a cliché about the unknowableness of other people from the contrasting perspectives of these opening chapters, but the richness of the portraits (together with the deft shift in time) serves an opposite effect. Even more than in “Found Objects,” “The Gold Bug” richly studs familiar types and situations with peculiar details. It is set on a day in which Bennie decides to do something unusual, as if on a whim but in fact to escape the oppression of his painful memories, which, the opening sentence tells us, “began early that day.” The unusual thing will be to pay a visit to the sisters who front for a failing band that he signed a few years ago. He’s got to drive up to Westchester anyway, to spend the afternoon with his nine year-old son, Christopher.

This earlier appointment would be dreary and depressing for both father and son, we’re assured, if it were not for Bennie’s carelessness, which leads him to take out his little box of gold flakes in front of Christopher, who of course instantly wants to taste one. We are thus distracted from the low-grade ordeal of a divorced father trying to pass a few hours in the company of a boy with whom he no longer lives — but we never forget that we’re being distracted. Nothing happens to suggest that the gold flakes have brought Christopher closer to his father. He’s just taking an ordinary boy’s delight in doing something different and probably improper.Â

A further distraction supervenes in the basement of the sisters’ Mount Vernon house, where the simple live-ness of the music awakens Bennie’s “rapturous images,” he he joins in the jam session by whacking a cowbell. We have seen this sort of thing before, too, but Egan doesn’t let it go on for more than a moment. “And from this zenith of lusty, devouring joy, he recalled opening an e-mail he’d been inadvertently cpied ion between two colleagues and finding himself referred to as a ‘hairball’.” There is simply no escaping these humiliations! For someone who dwells on lost youth, no present happiness is ever strong enough to defeat the insinuation of an old shame. Bennie’s attempt to escape into the heedless orgies of the past is of course doomed, but Egan gives it a particularity that makes us dream for a moment that it might succeed. We feel with and for Bennie even though we know that he’s just another jerk who liked life better with “the half hard-on that had been his constant companion since the age of thirteen.”Â

The curious thing, the special thing about Jennifer Egan is that her interest in shame — a force of which she has an engineer’s understanding — is uncoupled to any sense of alienation. Nothing is more private, more personally difference-making than shame, but if Egan gives us characters who feel this wretchedness acutely, the very fact that they feel it creates a common ground. Not for them, perhaps, but for us. Sahsa and Bennie are like two beautifully sketched trees that, we’re told, stand not far apart in a forest somewhere. What we do, effortlessly, is to sketch the ground between them. The sketch may lack detail, but it shows the ground to be firm. Alienation is just another feeling, just another shame, that establishes a shared humanity. The awfulness of life lies not in the fact that we’re unknowable to each other, interesting as that fact might be, but that it’s carrying us inexorably away from a youthfulness that we never knew, either, until it began to slip away from us.