Wednesday Morning Read

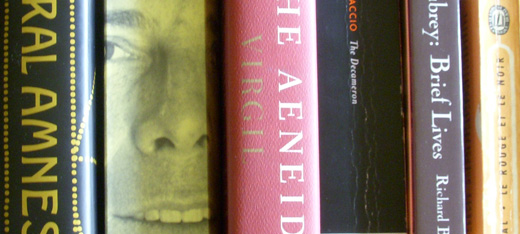

¶ In the Decameron (IX, vii), a shrewish wife ignores her husband’s foreboding dream, takes a walk in the woods, and is disfigured by an attacking wolf. The moral of the story, although coated with misogyny, is sound: don’t go out of your way not to take good advice. Although it can’t be easy to take advice that begins:

“Donna, ancora che la tua ritrosia non abbia mai sofferto che io abbia potuto avere un buon dì con teco…“

“Woman, your cussedness has been the bane of my life since the day we were married…”

¶ In Aubrey: Milton and Monck. The famous general, later Duke of Albemarle, did not invade England in 1660 with a view to restoring the Stuarts, but that is what happened, in what seems like a classic case of English muddling through. Aubrey, ever a royalist, delights in describing maypoles and other festivities proscribed durng “the hypocritical times.”

As for Milton, Aubrey gives us a sheaf of notes, including the draft of a letter requesting further information about the learned man and poet, “much more admired abroad than at home.” Aubrey provides this surprising detail: “His harmonical and ingenious soul did lodge in a beautiful and well-proportioned body.” There is no hint of the terrible sourpuss who roars from every page of Paradise Lost.

Typical Aubrey:

His eyesight was decaying about twenty years before his death: enquire, when stark blind? His father read without spectacles at 84. His mother had very weak eyes, and used spectacles as soon as she was thirty years old.

But this tops everything:

He was scarce so tall as I am — question, how many feet I am high: answer, of middle stature.

¶ In Merrill, a poem for this electoral season: “Snow Jobs.”

Where’s Teapot Dome? Where’s the Iran

Contra Affair? Where’s Watergate —

Liddy — Magruder — Ehrlichman?

Their shoes squeaked down the Halls of State

Whoe networks groaned beneath their weight,

Till spinster Clotho darted near

To shroud in white a running mate.

Ah, where’s the slush of yesteryear?

¶ I cannot even think about Clive James’s tangent on the Italian philologist Gianfranco Contini (whom I’d never heard of) without sighing very heavily. In these decayed times, I find, to my dismay, that I pass for educated. James gets right to the heart of how and why I am not, causing me to gnash my teeth at the recollection of how clever I thought I was not to have to study Latin and not to have to memories great swaths of poetry. By the time I got to college, it was too late. Now, instead of Dante and Shakespeare, my head is full of Firesign Theatre, Fawlty Towers, and Ruth Draper: a true child of the LP am I.

On one of my most treasured recordings, Wallace Stevens reads his long poem, “Credences of Summer.” I have not attempted to commit this poem to memory, and I have no idea what it’s about, but I do love it, and lines from it pop into my head all the time.

This is the barrenness

Of the fertile thing that can attain no more.

As if twelve princes sat before a king.

Listening to the recording many, many times has imprinted the rhythm of the poem on my mind (although, whenever I read the lines aloud, I don’t follow Stevens’s manner at all). It is almost as good a thing to listen to poetry (a lot) as it is to memorize it.