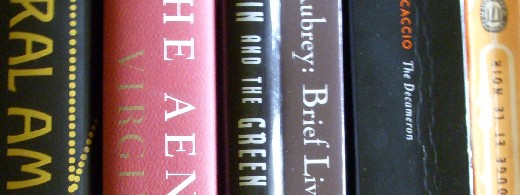

Thursday Morning Read

Reading the rest of Fitt III of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, I see that Fitt IV (the conclusion of the poem) is only seventeen pages long, if you ignore the facing original; so I shall read all of on Monday. On the following Monday, I’ll dip into James Merrill.

¶ The Decameron, VII, iii: the very off-color story of Friar Rinaldo and the worms. Off-color not so much because of what happens as because of Boccaccio’s language, which once again exploits a blasphemous misuse of sacred terms. (Guess what “Teaching the Our Father” stands for.) And before the story even gets going, Boccaccio lets rip a tirade against monks who, far from observing their astringent vows, live like coddled milords. His heart doesn’t seem to be in the wife’s-trickery angle.

A quibble with the translation. McWilliam has Boccaccio accusing the monks of “effeminate” behavior, but there is no real support in the original for this pungent slur. “Mincing” — for which there would be only slightly more justification — would have been vastly preferable. The problem with “effeminate,” and the thinking behind the use of the word, is that it insults, with the sloppiest imprecision, people of both sexes. Banish the term from your vocabulary to the attic, alongside “meticulous.”

¶ In the Aeneid, tears before gore.

percusse mente dedere

Dardanidae lacrimas, ante omnis pulcher Iulus,

atque animum patriae strinxit pietatis imago.

Such virtue as this verse possesses is sewn up tight within its Latin. And, as for this:

simul ense superbum

Rhamnetem adgreditur, qui forte tapetibus altia

exstructus toto proflabat pectore somnum,

rex idem et regi Turno gratissimus augur;

sed non augurio potuit depellere pestem.

tris iuxta famulos temere inter tela iacentis

armigerumque Remi premit aurigamque sub ipsis

nactus equis ferroque secat pendentia colla;

tum caput ipsi aufert domino truncumque relinquit

sanguine singultantem; atro tepefacta cruore

terra torique madent.

the elegance of the presentation is the only thing that renders the mayhem supportable.

¶ In Aubrey, the last of the Bs: Bushell, Butler (Samuel), Butler (William), Bysshe. From the crabbed delights of Aubrey’s style, I choose the following, from the life of Dr William Butler — a physician of many eccentric cures:

He kept an old maid whose name was Nell. Dr Butler would many times go to the tavern but drink by himself. About 9 or 10 at night old Nell comes for him with candle and lanthorn and says: “Come you home, you drunken beast.” By and by Nell would stumble; then her master calls her “drunken beast,” and so they did drunken beast one another all the way till they came home.

Just imagine a worthy medical man behaving like that when Victoria was Empress of India!

¶ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: On the third day of Gawain’s “ordeal,” while the master is out hunting a fox — and it’s clear that the pursuit of this rather useless prey (compared to the deer and boar of the previous days) strikes the poet and his listeners as much greater sporting fun. In any case, it means that the master doesn’t have much of a haul to hand over to Gawain, in exchange for, this time, three kisses.

What are we to make of the fact that Gawain keeps the lady’s girdle, which she has pressed upon the knight as anti-smiting protection, in contravention of his agreement with the master? The poet does not comment at this time. That’s another reason for finishing this off tomorrow: I want to see how it comes out!

¶ If Le rouge et le noir were an opera — the second part of the novel, anyway — it would be an opera about people being operatic. I’ll give the following delicious scene, in which Julien responds preposterously to a slight from Mathilde, as they converse for the second time since their assignation (after their first encounter, “ils en furent bientôt à se déclarer nettement qu’ils se brouillaient à jamais”) in Roger Gard’s translation:

Transported by misery, dazed by surprise, Julien had the weakness to bring out, in the tenderest and most heartfelt manner — Then you don’t love me any more?

— I’m horrified at having given myself to the first comer, answered Mathilde, weeping tears of rage against herself.

— To the first comer! exclaimed Julien, and he sprung to an antique medieval sword which was kept in the library as a curiosity.

His pain — which he had thought extreme when he spoke to Mlle de La Mole — had now been increased a hundredfold by the tears of shame he saw her shed. He would have been most happy to have had the power to kill her.

Just as he succeeded, with some difficulty, in drawing the sword from its ancient scabbard, Mathilde, delighted at so novel a sensation, advanced proudly towards him; her tears had dried up.

The image of the Marquis de La Mole, his benefactor, came vividly to Julien’s minds. And I am about to kill his daughter! he cried to himself — How appalling! He made as if to throw the sword from him. Certainly, he thought, she is going to burst out laughing at the sight of this melodramatic gesture — and the thought helped him regain complete possession of himself. He examined the ancient blade attentively, as though looking for a speck of rust, then put it back in its scabbard with the greatest of calmness, hung it up again on its gilded brass nail.

The whole of this episode, much drawn out toward the end, had lasted a good minute; Mlle de La Mole stared at him in astonishment. I have just been on the point of being slain by my lover! she said to herself.   Â

The idea carried her off to the finest days of the age of Charles IX and Henri III.

The only way to conceive of justice being done to this material is to imagine Mozart living into a ripe old age, settling in Paris, and collaborating with the young Berlioz — nay, prodding him on, firing him with the glories of da Ponte’s verses. And this idea is every bit as funny as Julien’s swordplay.

¶ Clive James is at his very best with Waugh. His preface, written for Cultural Amnesia, leads with the greatest piquancy to a quotation from Waugh that the ensuing brief essay, which is actually on the near-challenge that democracy poses to grammar, holds up for roasting.

Having praised Waugh in a rescuing sort of way, beating down his detractors, James introduces a plaint of his own:

His apparent conviction that only those with a public school (i e private school) education in classics could write accurate English was a flagrant example of the very snobbery he was attacked for. It also happened to be factually wrong, on the evidence that he himself inadvertently provided.

Well, after that setup, who can fail to miss what’s wrong with this, from Waugh’s A Little Learning (“Tony” is Anthony Powell):

A little later, very hard up and seeking a commission to write a book, it was Tony who introduced me to my first publisher.

James lets this solecism dangle in the wind for the entire length, not short, of the opening paragraph of the essay proper. Then he lowers the boom.

Only a few pages away from that claim, he wrote the cited sentence, which is about incorrect as it could be, because he ends up talking about the wrong person. He meant to say that it was he, Evelyn Waugh, who was very hard up, and not Anthony Powell. To make this lapse more delicious, Powell himself was the arch-perpetrator of the dangling modifier.

I’m not so sure that I’d have signed off on that second sentence; for, if there is no dangler, there is the ghost of one. Powell hardly “perpetrated” this most shibboleth-y of English grammatical errors in order “to make [Waugh’s] lapse more delicious.” But the ghost smiles, and makes my reading pleasure, at any rate, more exquisite still.