Friday

After a bit of a relapse on Thursday, I rallied yesterday afternoon, at least enough to run across the street to the movies, to see Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Although it’s full of very fine performances, I’m not sure why it was made. Was the miniseries with Alec Guinness out of date? Was it thought prudent to provide younger viewers with a sexy reminder of the Cold War?

Sunday

All of a sudden, it is the middle of the afternoon, about to start getting dark. I slept in a bit — not as late as I’ve been doing, but ruinously nonetheless for my dreams of getting things done. By “getting things done,” however, I no longer mean working my way down a to-do list. I mean finding the rhythms that will make it more likely than not that to-do lists won’t grown to inordinate lengths. This entry is part of the experiment; never, in fact, has blogging felt anything like so experimental to me. In part, I’m using the blog as a scratch pad for more or less literate notes. But I’m also cultivating it as a place that I can drop in on without a great deal of self-conscious fuss. Maybe sleeping in wasn’t so ruinous, after all.

I’ve spent an hour grappling with Marilynne Robinson’s Absense of Mind: The Dispelling of Inwardness From the Modern Myth of the Self. Presented as a series of lectures, the fabric of Robinson’s thought is uncommonly dense, and not always as lucid as at first appears. The gist, to far, seems to be: Not so fast! She objects to the modern penchant for assuming the humanity has crossed a threshold, beyond which old assumptions and habits of thought — most notably, belief in God — are no longer valid and must be discarded. I agree with her, that the habit is gross; terms remain undefined, the location of the threshold shifts from argument to argument, and the past is almost always misread with condescending simplification. Beyond that, however, I haven’t been able to advance.

I do believe that a threshold has been crossed, and that things are different on this side of the passage. For me, the threshold was the repudiation of Papal authority by many bands of self-styled Christians during what we call, quite misleadingly, the Reformation. Papal authority was repudiated not in favor of some other insitutional authority (however many intermediate steps marked any denomination’s departure from orthodoxy), but in recognition of something newly felt to be pressing by many European minds in the early Sixteenth Century — it had been felt earlier, but now it was felt by many — and I call this something the sacrosanct nature of every soul’s individual relationship with its Creator. I think that we’re still getting used to this remarkable idea, that each and every one of us is equally special in the eys of God — that is to say, equally distinct. Appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, I am not significantly like you. Most of us probably don’t really accept this, especially if we’re unusually gifted, in which case it seems obvious that the talented few stand out from the crowd of ordinary people. But there is really no way to argue the protestant claim — in today’s terms, I would say that no other human being has the right to govern my understanding of and honor for the world I live in — without allowing it to every man and woman on earth, everywhere.

In the terms that Isaiah Berlin would use, establishing the paramountcy of the personal relationship with God was a freedom from. We have been looking for the corresponding freedom(s) to ever since. Many people, some of them quite gifted thinkers, have found the task of filling the space once occupied by ecclesiastical pronunciamento to be extremely taxing; many have felt despair. Is it true that, without God, everything is permitted? What kinds of truths can be admitted, if we see ourselves as accidental productions of impersonal evolutionary forces?

I would add this question: what is vital and interesting about the autonomous self? My hunch is that the answer involves the multiplicity of relationships that we forge with each other. I believe that “society” is the result of all of these relationships, something of which we all have a strong but inexorably imprecise understanding. These are notions that I will keep to the fore as I read Marilynne Robinson’s demanding book.

Also interesting, if nowhere near so taxing, was Garth Risk Hallberg’s essay in the Times Magazine, “Why Write Novels At All?” At the heart of his argument lies a book that came along “after my time,” Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction. I bought a copy recently and found the book to be mercilessly cynical. Its governing idea, I gather, is to apply truisms that have always been made about pretensions of social status to the hitherto “transcendant” world of art, so that a taste for Jane Austen is morally equivalent to a taste for Jimmy Choos. I reject this idea, because I believe that a taste for Jane Austen will significantly influence the kinds of relationships that I forge with other people; to the extent that my taste for Jane Austen is a good taste — as opposed to the obviously sentimentalizing taste that “allowed” some Germans to venerate Beethoven and Goethe while herding Jews into death camps — my relationships will be better, healthier relationships: I’m not ashamed to say that I believe that. The fact that I’ve been permitted by good fortunate to develop a taste for Jane Austen in no way diminishes its virtue; nor do I derive any conscious satisfaction from the suggestion that my taste for Jane Austen is uncommon, that it makes me stand out among men. I derive only sadness from that observation. I wish that everyone shared my good fortune. Meanwhile, I’m trying to make the best of it.

Hallberg argues that what he calls the “Conversazioni group” of novelists — Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides, and others — have only intermittently succeeded at making the case that “there are other people besides ourselves in the world, whole mysterious inner universes.” I don’t know why the exercise of imagining someone else’s inner universe is laudable or even desirable. Wouldn’t the hermeneutics of postmodernism suggest that the mere having of an idea of what it’s like to be someone else is probably a delusion, and certainly an appropriation, and imposition of yourself upon that someone else? And isn’t it simplistic to imagine that “whole mysterious universes” could be intelligibly grasped? What I want to know about other people is not what they’re “really feeling” — I’ve learned that the sense of what I’m “really feeling” is usually no more informative than a fun-house mirror — but what they’re really prepared to bring to any relationship. I’ve also learned that, if someone else doesn’t wish to have a relationship with me in the first place, I will probably never understand why.

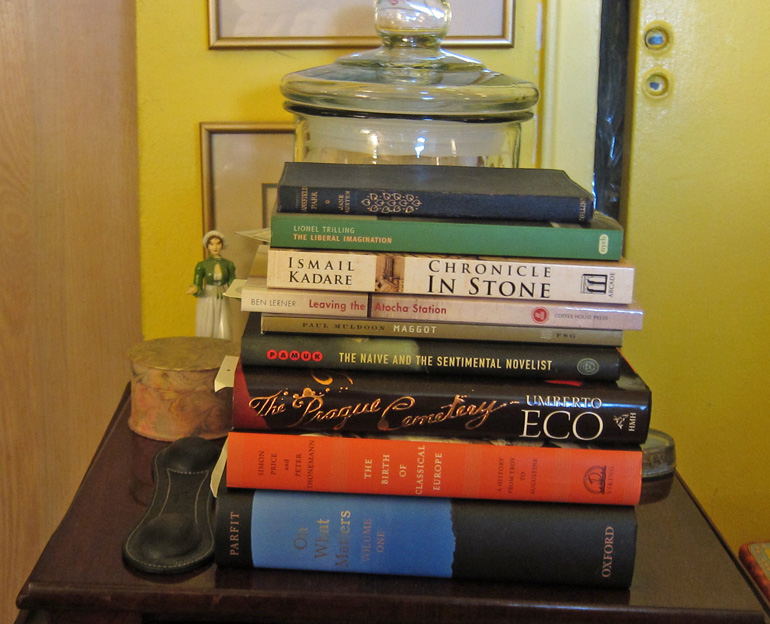

Meanwhile, I’m wondering, in light of all of this, why I think that Chris Bachelder’s Abbott Awaits and Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station are really good novels that everyone ought to read, even though they are so focused on individual male points of view that it’s hard to imagine Garth Risk Hallberg giving either of them the time of day. Is it just that they’re both superbly well-written? And what would that mean?

Monday

How nice to have a three-day weekend in the middle of January, especially as one is able to appreciate it now that one has recovered a bit from holiday colds! I made a bacon breakfast, which is to say that I put a pan of thick-sliced bacon in a hot oven for an hour, turning every twenty minutes. For the first twenty minutes, I sat in the bedroom and did not read the Times. No! The best way to start the day is by writing, but the second-best is by reading anything but the New York Times — the writing just gets worse and worse. I picked up instead Peter Conrad’s Verdi and/or Wagner and read a lot of blather (I thought) about the nationalist backgrounds (or not) of the two great opera composers. There are a lot of Wagner quotes, because Wagner was a prolific writer of tracts and treatises — a genuine windbag. In contrast, Verdi, left to himself, would, I think, have gone in for sheer muteness, contributing nothing but his scores to the general conversation (and all those letters to his librettists). As a remarkable side-effect of the morning’s reading, I may have nailed the difference between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines once and for all. The original Guelphs were Braunschweiger notables who supported papal claims to imperium as a way of centralizing power in a distant city and letting geography neuter it. Later, they became the Hanoverian kings of England, and did not support the Pope in any way. Don’t take my word for any of this.

Catching up with Facebook yesterday, I learned that a friend became the father of twins on Friday. Very good news indeed! It took me back to a conversation that we had, not all that many years ago, over drinks on the terrace at the New Leaf Café, after a tour of the Cloisters. My friend talked about wanting children, and I talked about wanting grandchildren. Our difficulties were similar: neither he nor my daughter was in a relationship at the time. All that has since changed. My wish was granted two years ago, and now my friend is equally fortunate. I wish him all the best, &c — but what I really would give him if I could is the concentrated somatic supplement for all the sleep that he is going to miss in the next few years. And I hope that one of his children will make him a grandfather before he is too very ancient. Â

***

I can tell you exactly why it took me forever to get round to seeing The Descendants: Hawai’i. I have only one good thing to say about Hawai’i: I hope that we give it back. On the basis of a few days in Waikiki and at the Howard Johnson motel near the airport, I can say that, given the ultimatum, I would rather live in New Jersey, and I can’t think of anything worse to say about anywhere.

We went to see the movie late this afternoon, thinking schizophrenically that the showing would be deserted because it has been at the East 85th Stree Theatre for weeks and weeks, and also that it would be crowded because of the Golden Globes. I said to Kathleen: we must leave at ten past four. We left at twenty past, and bitter recriminations, if not an outright divorce, might have been in the offing if it hadn’t been for a miraculously empty pair of seats by the aisle in the last row right as we entered the theatre.

Alexander Payne’s production values back me up about Hawai’i: everything manmade in out there is a monstrosity, or else a sad old fading stucoo villa, like the house, not very imposing, in which Matt King (George Clooney), trustee of an enormous settler windfall, has parked his family. He insists on living on the interest, not the principal, of his family’s wealth, and makes a mortal enemy of his cheating wife’s father-in-law. Given the shabbiness of his maison, it’s rich to hear his father-in-law, played by Robert Forster, complain about his cheapness, his stinginess, his refusal to spend his money. Money that Matt King, a proper New Englander however trasnplanted, doesn’t believe is his own. The miracle, of course, is that the movie makes you care, deeply, about Robert Forster’s daddy’s-girl dad. He’s a shit and a chimp, but you weep for his sorrow.

As in all Alexander Payne movies, we are treated to the way in which Americans actually behave, particularly our penchant for the crashing juxtaposition of high-mindedness and comic relief. Americans are the most professionally nice people to adorn the homo sapiens family tree, but their sweetness and patience have definite limits, and The Descendants is a kind of catalogue raisoné of closure. As in all the best George Clooney movies, we’re treated to a few moments of crazy George, stalking his wife’s lover with the autonomatic intensity of Charlie Chaplin. Matt King is a good guy, really; never once does he yield to the misery of discvoering his wife’s infidelity; never once does he seize high ground as the honorable partner. His workaholism, if that’s what it is, may have made him inattentive to his wife and daughters’ life at home; equally, you think that this is a guy who ought to have had sons — the advice that his older daughter’s marvelously cloudy boyfriend, Sid, offers when Matt asks how to deal with his girls now that their mother is in a coma and dying. (“I’d trade them in for sons, I don’t know.”) But sons are not essential. At a key moment, it’s Matt’s older daughter, played with aplomb by Shailene Woodley, who nudges her father with “Don’t be a pussy.” That’s a line that only underscores what you’re already thinking, which is that only Cary Grant could have played this role, until Clooney that is.

Only Cary Grant. The moment in the Kaui’i restaurant, after Matt has just discovered that his wife’s lover will hit it rich as the realtor connected to the development of his family’s property, when you realize that Matt just wants to throw up but must somehow sit through a family meal. Much of the excitement of The Descendants consists in Clooney’s beein joyfully less violent than you think he might be. His big tantrum involves throwing a stuffed bear across a room. The rest of the time, he is a model to us all. He hits no one and is unfailingly decent. Payne knows how to make this restraint look as heroic as it ought to do, and we are deeply in their gift.

We’ll save our talk about developers for another time.

Â

Â

Â