“It was a tough week.” That’s how I put it to myself. But I can’t put it that way here, without the quotation marks, because there was nothing objectively tough about it all. I was unaccountably tired at the beginning, and also worried about something that it took a while to clear up. By Wednesday afternoon, I was celebrating Fossil Darling’s birthday, and very much in the mood. Thursday was not unproductive but somewhat strange, because it dawned on me at about five o’clock that I was going to have to think hard about what I was doing if I was going to get myself into bed at ten. Which I did, although I did not fall asleep at once. Friday morning, I was up at six: success at last.

But it’s tough to be tired, for whatever reason. Fatigue takes on an existential dimension with age: it becomes awfully easy to imagine that you’re never going to shake it. Regular life doesn’t seem worth the effort. Little household tasks seem too tedious and trivial to consider, which is another way of saying that they become disproportionately momentous. (Why even think about putting the laundry away?) There’s an element of clinical depression that would be more than merely elemental if the fatigue were allowed to become chronic. For me, the source of fatigue is very simple: it comes from staying up too late and drinking too much wine. These vices go together; for decades, they were the only route to sleep. Now that I’ve been taking Lunesta for a year, I’m beginning to believe in a healthier routine, but at least thirty years of habit have to be ripped up, and a very attractive part of the habit is the pleasure of talking with Kathleen at and after dinner — dinner which, owing to her hours, rarely occurs before nine o’clock, and never before seven-thirty.  Â

***

At long last, I figured out how to cook chicken breasts. Why it took so long — well, it took so long because, as with so many little things in life, I tend to believe, like the nitwits in Molière’s Précieuses ridicules, that “Les gens de qualité savent tout sans avoir jamais rien appris.” Use your head, in other words — but, sometimes, using a recipe is better, and it this case it wasn’t even a recipe, just a Mark Bittman sketch about things to do with chicken breasts that appeared in the Times Magazine a few months ago.

I knew that I’d figured out how to cook chicken breasts this time because they were tender and moist and slightly spongy — and full of flavor. Yes, I used curry, but there was a delicious chicken taste underneath it.

Here’s what you do: Heat two tablespoons of butter and a half teaspoon of curry powder in a gratin dish, in a 400º oven, for about six minutes. Take the dish out of the oven, and roll the chicken cutlets in the melted butter. Pop back into the oven, cooking the chicken for six minutes on a side. Then turn the oven off and open the oven door a bit. You can leave the chicken in the oven for up to five minutes.

The trick is to find out what the times for your oven will be.

***

While tidying the flat on Saturday, I found myself in a mood to listen to speaking, not singing, so I rifled through my small collection of audiobooks and came upon a treat: Ben Kingsley reading Sherlock Holmes stories. It has been decades since I last read Conan Doyle. I do not believe that he wrote for adults, and his detective adventures are larded with the most preposterous nonsense. When the incognito “king of Bohemia” refers to his upcoming nuptials, and the reason for his anxiety about a photograph of himself in the company of Irene Adler, for example, I can only burst into hysterics.

“To Clotilde Lothman von Saxe-Meiningen, second daughter of the King of Scandinavia. You may know the strict principles of her family. She is herself the very soul of delicacy. A shadow of a doubt as to my conduct would bring the matter to an end.”

It’s not the “king of Scandinavia” bit that tickles me. It’s the idea that doubts about a prince’s private love-life would interfere with a dynastic marriage. (In the real world, they just might — if he didn’t have one!) Such passages let all the air out of the tire for me. I wonder what Princess Alexandra (as she then was) made of this one.

I remember taking especial delight, when reading this stuff in my twenties, in the formal tics, my favorite being Holmes’s heralding the arrival of the client in Baker Street.

“Precisely. And the man who wrote the note is a German. Do you note the peculiar construction of the sentence — ‘This account of you we have from all quarters received.’ A Frenchman or Russian could not have written that. It is the German who is so uncourteous to his verbs. It only remains, therefore, to discover what is wanted by this German who writes upon Bohemian paper and prefers wearing a mask to showing his face. And here he comes, if I am not mistaken, to resolve all our doubts.”

As he spoke there was the sharp sound of horses’ hoofs and grating wheels against the curb, followed by a sharp pull at the bell.

Ben Kingsley is, needless to say, divine. As I dust the knickknacks and wipe the bibelots, I couldn’t feel more like Mrs Turner.

***

For breakfast on Sunday morning, I made a pot of cofee the old-fashioned way, with a stove-top percolator. I filled the pot with four cups of water, and then I put four tablespoons of reasonably good, appropriately ground coffee from Fairway in the basket. I set the pot over high heat. The moment a jet of water erupted into the glass dome, I turned down the heat, and kept turning it down, over the course of a minute, to rather low. Once the pot was spouting along nicely, I let it go for ten minutes. The result is very satisfying! It’s certainly nothing like the Kona that I brew in the Chemex, but that’s a weekend specialty for the two of us. Also, I’ve never figured out how to make small amounts of coffee with a Chemex, even with a little Chemex. Now I can start the day with a couple of cups of good-enough coffee.

Also a reminder of childhood. The percolator was the first item of kitchen appliance that I ever noticed, or perhaps the second, after the eggbeater. Did I tell you that Ray Soleil gave me his grandmother’s eggbeater? You can’t get them anymore. I’m talking about the hand-cranked type, of course. It’s really the only way to beat eggs for scrambling. (Because of its wooden handle, this eggbeater cannot be run through the dishwasher, so I soak the blades in warm water once I’ve poured the eggs into the skillet. A little soap, a little beating, a quick rinse — done.)

The soft percussion of a bubbling percolator says “breakfast” like nothing else in the world.

***

By Friday, I was strong enough to do a bit of running around, but not quite strong enough not to feel it. I began with a burger at the Shake Shack — I hadn’t been there in a while. Then I marched to the Museum, where I attended to a dereliction in our membership. The word for my membership renewal policy has been, for several years, “drift.” Originally, probably like a lot of people, we renewed at the end of the year. This is a terrible time for that sort of thing, given all the other expenses of the holiday season. So I took to renewing a day or two after our membership expired, which effectively postponed the following year’s expiration by a month. (Membership is YYMM, not YYMMDD.) This year, I had things just where I wanted them: I was set to renew on the first of June. But June went by without my making it over to the Museum, and so did most of July.

You may wonder why I didn’t simply return the renewal form supplied by the Musem, why I had to renew in person. That’s because of the other drift, which has been upwards through the ranks of membership. We have found the limit, I think; the gulf between our membership and the next rung up is a multiple of what we’re paying now — which is already enough for me to think it better to divide the weight between two credit cards, much easier to do in person. As I did on Friday.

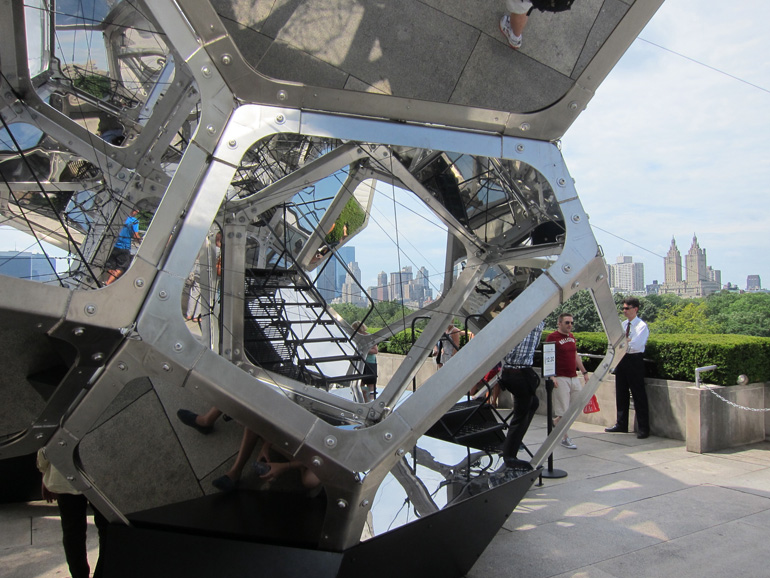

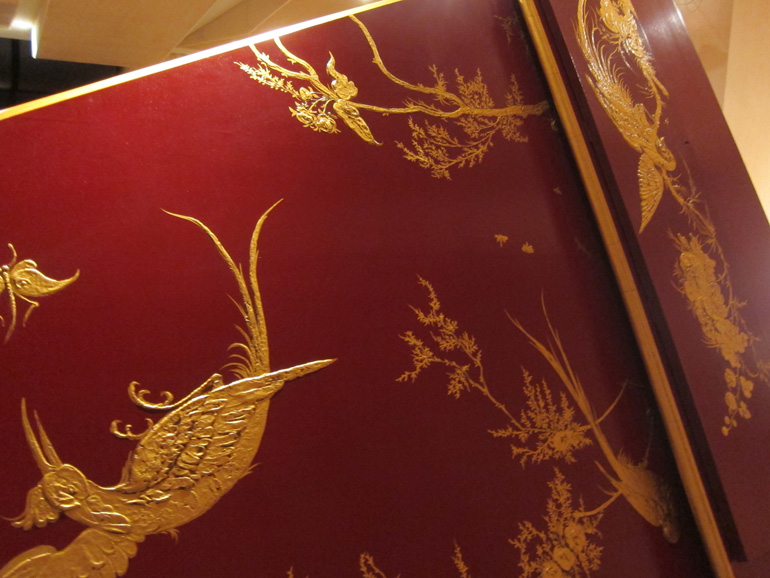

Then, since I was already there, I took in the Schiaparelli/Prada show, which I must drag Kathleen to, since I’ve never seen so many clothes that looked designed just for her. Then I went up onto the roof, really just to take pictures. There is something odd about the Roof Garden; it has, rather, a seaside air, and not in the just the nice ways. So many fagged tourists looking exhausted on the benches! So much sun, or other intense weather, beating down! Instead of sand, the treetops, and, instead of the sea, the skyscrapers. Two kinds of wilderness: the forest that is Central Park, and the riot of development beyond it. Until 150 years ago or so, civilized people anywhere would have found the juxtapositions bizarre and somewhat barbaric.

On my way to the egress, I thought of my knees which are still a bit swollen from my climb-down a few weeks ago (thinking that I’d be late for a movie if I waited for the only elevator in service, I took the stairs almost all the way down to the ground, something that I will Never Do Again except in case of fire), and decided to spare myself the descent from the main entrance. I walked instead to the elevators in Greece and Rome, and went down to the group/Children’s Museum/handicapped entrance. This put me out at 81st Street, which was fine, since I was heading for Crawford Doyle. I’d forgotten, though, that this route would take me alongisde Frank Campbell — not just the front, which is for the living, but alongside, where two staffers were doing something with an empty gurney. Such sights stir one’s mind. Â

***

There seems to be something cooking at Crawford Doyle. Whatever it is, it makes me read the books that I buy there right away. It happened with three books a few weeks ago; now it’s just happened with two. Two of the books that I bought on Friday were read by Saturday afternoon. And I loved them both.

The first was J R Ackerley’s We Think the World of You, which I would call a novella, even though NYRB has published it unaccompanied by other material. It appears to be Ackerley’s only work of fiction. Although it is very well put together, and you’re aware of that as you read it, the book feels as wild as the animal at its center — which is either a large sheepdog of some kind called Evie, or a condescending gay twit, depending on your point of view. The twit speaks English of a sort, and holds down a government job in a building “in the neighbourhood of Regent’s Park” (why not just say “Marylebone Road”?), but is as lacking in self-awareness as any beast — as, say, Humbert Humbert, or one of Patricia Highsmith’s more demented characters. That’s where the thrill comes from: Frank, the narrator, is so dangerously presumptuous about the ground that he walks on that he can’t imagine it giving away beneath him, which it very nearly does several times. It’s the danger looming all round him that makes Frank bearable — as a potential human sacrifice. I kept longing for him to be crushed. The book’s ending, according to P N Furbank, is “minatory,” and certainly far from happy, but I wanted blood, which was very shaming.

At the beginning of the book, Frank’s lover, or “lover,” Johnny — a feckless cockney charmer loaded with short-term shrewdness but utterly devoid of long-term intelligence, and also, by the way, saddled with a wife, a son, and a baby on the way — asks Frank to take care of his dog while he’s in prison. Johnny has botched an experiment in housebreaking and will be spending a year behind bars. Frank refuses to help out, which is very typical of Frank, who thinks that he’s very generous but who measures out his gifts in shillings. Only later, when he’s visiting Johnny’s mother, Millie (who used to be his char), does Frank meet, and fall in love with, Evie, a very large dog who is not being properly exercised, not, at least, by Frank’s Country Life lights. Without being aware of what he’s doing, Frank transforms Evie into a substitute for Johnny. That’s to say that he’s too worldly and established to imagine that he can engage in a custody fight for Johnny with HM Prisons, so he takes up instead against Millie and her husband and Johnny’s wife, and even the wife’s daughter by a previous engagement, in a contest for possession of Evie. And the issue, not very thinly disguised, is class. Just as Frank thought that Johnny’s family ought to have yielded Johnny up to him, as the far better companion for their son and husband, before the incarceration, so now he insists that he is the only one who can provide Evie with lots of space for galloping about and being unruly to strangers.

It’s almost impossible to believe that this book came out in 1960, when homosexual practices were still sanctioned in Britain.

I’ve probably made it sound gruesome and sordid, but We Think the World of You is a sparkler that it’s impossible to put down. Here is Frank, after his one and only visit to Johnny in prison, near the end of the sentence, expressing the bipolar contrition that swells up in him after he has indulged his “well-bred” contempt for Johnny’s family:

This interview, when the emotional pleasure of seeing Johnny had worn off, left me feeling unaccountably tired and flat, and as my thoughts, in the succeeding days, reverted to it and wandered dully among its shoals and shallows, I found myself afflicted by a despondency which had nothing to do with the perception that I had been put, to a large extent, in the wrong. Say what one might against these people, their foolish frames could not bear the weight of iniquity I had piled upon them, they were, in fact, perfectly ordinary people behavving in a perfectly ordinary way, and practically all the information they had given me about themselves and each other had been true, had been real, and not romance, or prevarication, or the senseless antics of some incomprehensible insect, which were the alternating lights in which, since it had not happened to suit me, I had preferred to regard it. They simply had not wished to worry Johnny, and, it was plain enough, he had had much to worry him already; he had cared about the fate of his dismal wife and family, as Millie had cared about Dickie, and, for all I knew, Tom about Evie; the tears Johnny had shed over his dog had been real tears and, there was no doubt of it, he had terribly missed his smokes.

(I roared with laughter.)

Their problems, in short, had been real problems, and the worlds they so frequently said they thought of each other apparently seemed less flimsy to them than they had appeared to me when I tried to sweep them all away. It was difficult to escape the conclusion, indeed, that, on the whole, I had been a tiresome and troublesome fellow who, for one reason or another, had acted in a manner so intemperate that he might truly be said to have lost his head; but if this sober reflection had upon me any effect at all, it produced no feeling that could remotely be called repentence,

(See what I mean?)

but only a kind of listlessness as though some prop that had supported me hitherto had been withdrawn. Yet Johnny had been perfectly nice; what better proof of his affection could I have than the thought that had come to him in the solitude of his cell of calling his new child by my name? And I could have his dog. And soon I should have him…. Indeed, I had everything, except the sense of richness, and when the phrase “I ‘ad to do me best to please everyone” recurred to my mind, I wondered why so admirable a sentiment made me feel so cross. Beneath such a general smear of mild good nature, I asked myself, could any true value survive? Where everything mattered, nothing mattered, and I recollected that it had passed through my mind while I spoke to him that if the eyes that looked into mine took me in at all, they seemed to take me for granted.

Now, that’s what I call “Foney Baloney.” I will leave it to you to encounter Evie for yourself; I encourage you to do so! Â

About Harriet Lane’s debut novel, Alys, Always, I can say nothing for the time being, because the book is much too exciting to permit discussions that might betray its plot. I shall content myself, for the moment, with observing that, while I agree with whoever wrote passage blurbed from the Independent on Sunday, that the book is “in classic Ruth Rendell territory,” I must insist that it is a great deal more sophisticated in tone than the worthy baroness’s fictions, even the best of them. Alys, Always in in fact well-enough crafted to pass as something that Ian McEwan might have produced. The book is smashingly good, and, as a plus, it was for me a very interesting (and totally serendipitous) counterweight to We Think the World of You, because its narrator is an outsider who weighs and considers her every move and every word. The youngsters of our fair city will profit mightily from the study of this elegant handbook of ambitious restraint.