Gotham Diary:

East and West

13 January 2014

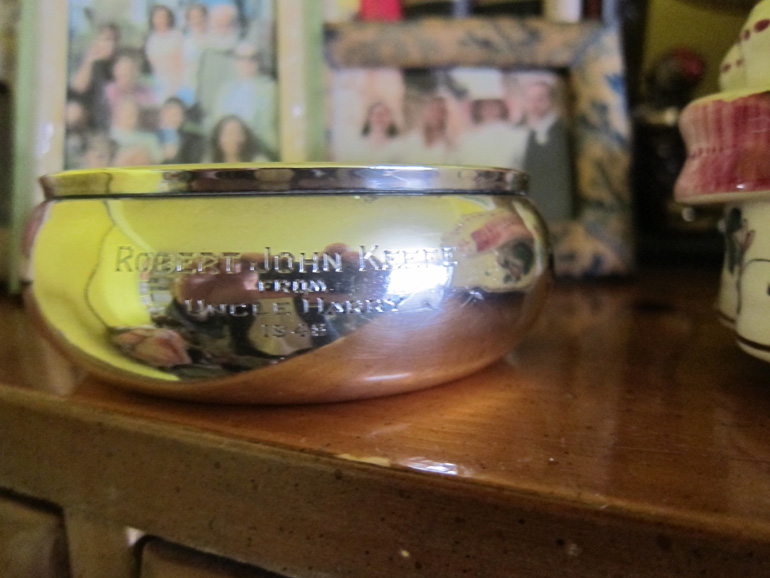

This weather will be the death of us all. Last week, it was either too cold to venture outdoors or wet, as shown above. I dearly wished to stay home today, but it was sunny and mild — just for the moment, with more wet on the way — so I had to take advantage of favorable winds and run a round of errands. Before lunch with Ray Soleil, I got a haircut, and stopped by Crawford Doyle. Also William Greenberg for cookies and Venture Stationery for Post-Its. After lunch, I bought a Le Creuset Dutch oven at Williams-Sonoma, to replace one that had cracked after decades of use, and made a quick stop at the bank. Back at home, Ray and I had a cup of tea — with some cookies. Then I went out again, to pick up prescriptions for Kathleen and to buy a couple of bratwurst at Schaller & Weber. Fairway turned out to be not too much of a zoo.

Now I don’t have to go out for a couple of days. (Gristede’s runs don’t count.) Tomorrow, I can continue some domestic maneuvers.

***

On Sunday, I read an item in the Times about the dueling matriarchs of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia. The first lady was recently re-elected as prime minister; the second instructed her followers to boycott the election, which it seems they did. This superficially amusing but basically depressing story would not have meant much to me if I had not finished reading, the day before, a book about the troubled country at the mouth of the great rivers, Srinath Raghavan’s 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh. I can’t remember why I bought it, but I’m pretty sure that somebody in one of the reviews gave it a strong notice. The book was hard going at first. Well, not at first; the first two chapters read briskly enough, as Raghavan relates the events leading up to the show-down between Agha Yahya Khan, the military president (dictator) of Pakistan from 1969, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, leader of the East Pakistani Awami League and winner of the 1970 parliamentary elections. Spurred on by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (who would replace him after the debacle), Yahya failed to yield power to Mujib. East Pakistan rose in revolt in early 1971. West Pakistani forces suppressed the disorder, but at the cost of inducing nearly a tenth of the local population to seek refuge in India.

Just when you are ready to read about chaos in what would become Bangladesh by the end of 1971, Raghavan turns his back on the scene, the better to survey the response of the rest of the world to the situation; that’s what his subtitle means. This is where the difficulty began. It was hard to adjust to the fact that I would be reading a diplomatic history, in which communiqués and ambassadorial conversations would take the place of events. The structure of the book was initally off-putting as well. In each of the six central chapters, the crisis is reviewed from the perspective of one of the following points of view: the Indian government of Indira Gandhi, the White House of Nixon and Kissinger (a point of view in sharp conflict with that of the US State Department), the Kremlin, the United Nations and the growing humanitarian movements, the other international players, and, finally the China of Mao and Zhou En-lai. Each of these chapters begins at some point in the Sixties and advances tortuously through 1971, usually ending just a bit further into the year than did the preceding chapter. At first, this recurrence was annoying, but by the time I got to China, I was mesmerized. It was clear that Raghavan was telling his story in the most suitable way, and the cumulative pile-up of detail demonstrated the ingenuity of his sequence.

In the last two chapters, Raghavan picks up the crisis itself where he set it down at the end of the first two chapters, and, if you’ve been paying attention, the narrative is as rewarding as a great stew is tasty. After months of restraint, war finally broke out between India and Pakistan in December 1971. It lasted for twelve days, after which Pakistan surrendered and withdrew its claims upon the eastern wing of the country. No other country interfered — except, of course, the United States. The United States sent a fleet from Vietnam, which, happily, did not arrive in the Bay of Bengal in time to do anything stupid.

It would be a mistake to accuse Raghavan of an anti-American slant, but he does make almost gleeful use of White House tapes to illustrate the dickheadedness of the two guys in the Oval Office. The president and his national security adviser had only one big thing in mind, but it was a very big thing: the world itself, as rearranged by a rapprochement between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China. In order to keep this matter of global strategic significance top secret, Nixon and Kissinger needed a supremo as their emissary, and the supremo they picked was — Yahya Khan. He did the job so well that the American plotters completely lost the ability to see the subcontinental crisis at all objectively. Yahya was great, therefore Pakistan was great. India was — ruled by a woman of whom the two men had nothing nice to say. (“That bitch played us,” Nixon would bay.) To be sure, Nixon and Kissinger are at a great disadvantage here. It is perfectly possible that that the chanceries of the world echoed with the same kind of pompous nonsense as passed for realpolitik in the Oval Office. But, if so, those inanities were not recorded. Americans aside, Raghavan is largely confined to the measured statements of governments. Everybody seems cautious — except the reckless, raucous Americans. “Pissing contest” is too polite a term for the kind of challenge Nixon and Kissinger imagined themselves to be faced with.

The United States was the odd man out in this game for another reason as well, the very simple one of geography. India and Pakistan are very far away from the US. They are very close to Russia and China, however, and the Russian and Chinese leaders acted as though this fact bore heavily on their thinking, as indeed it ought. Nixon and Kissinger were incapable of thinking on a sub-global level. Their grandiosity was ridiculous.

As government after government came to the same conclusion — the West Pakistani oppression of East Pakistan was regrettable and almost certainly bound to recoil upon the oppressors, but Pakistan’s sovereignty must be respected by other nations — I found myself more and more disgusted with the notion of “sovereignty,” at least outside of Western Europe and the English-speaking powers. As applied to the Pakistan of 1970, it made no sense at all. The borders were not yet twenty-five years old, and they had been drawn by outsiders. All that bound the people of East and West Pakistan was Islam and a history with the Raj. They shared neither culture nor economic outlook. Smaller by far in land area, East Pakistan was considerably larger than West Pakistan in population. That was the problem: after Pakistan’s first free and fair election, the parliamentary majority would have been held by a party that represented only East Pakistan.

Long before I reached the final paragraph of 1971, I was of the same mind.

The 1971 crisis also has a contemporary resonance well beyond the the confines of South Asia. For it proved to be a precursor of more recent conflicts in the Balkans, Africa, and the Middle East. The Bangladesh crisis prefigured many of the characteristic features of contemporary conflicts: the tension between the principles of sovereignty and human rights and the competing considerations of interests and norms; the virtues of unilateralism versus multilateralism; national lineups that blur the international divides of West and East, North and South; and the importance of international media and NGOs, diasporas and transnational public opinion. The Bangladesh crisis may have occurred during a watereshed moment in the Cold War, but it was a harbinger of the post-Cold War world. Inasmuch as it turns the spotlight on these dilemmas and debates, the history of the 1971 crisis is not merely a narrative of the past but a tract for our times.

Sheikh Hasina is Mujibur Rahman’s daughter. She survived the massacre of her entire family, in 1975, only by virtue of studying abroad. Begum Khaleda Zia is the widow of a president assassinated in 1981. Independence has not been kind to these ladies, nor to their country. We have a lot to learn.