Intellectual Note:

Having My Own Way

14 January 2015

In this morning’s Times, I read the obituary of Carl Degler, a Stanford historian who died at a great age. I was assigned his book, Out of Our Past: The Forces That Shaped Modern America, at prep school, fifty years ago. I did not read it then or afterward, but I carted it around with me for decades. I doubt that I still have it, but I can’t be sure without checking the shelves here and in storage. I was faintly surprised to read that Degler was an early advocate of affirmative action and feminism, because, it’s clear, I thought that he was much older than he was, or at least a lot more than thirty-odd years older than I was.

Out of Our Past was a large, thick paperback, unusual in those days, and I was put off by the jacket art, which featured a gigantic eagle frowning with righteous indignation. The image had clearly been lifted from a publication of the Civil War era, and I don’t think that anything could have been a bigger turn-off. I found the mere thought of the Nineteenth Century oppressive — all those black, hot, wrinkled clothes! All that untidy hair! (I was responding to old photographs; it would be a long time before I understood that earlier periods of history appealed to me because they had not been subjected to the scrutiny of photography.) And there was always something bogus about the Civil War. If it had indeed been the triumph of justice and freedom that teachers said it was, you certainly couldn’t tell that from looking at social arrangements on the ground. Black people tended to be poor. (Unless they were entertainers — a euphemism that one ran into. “There must be a lot of entertainers in your building,” said my mother-in-law to Kathleen in 1980.) They lived in unlovely places. They were conspicuously absent from my suburban hometown (which was popular with Southern expats). Triumph of hypocrisy would be more like it.

I should have liked my country better had the Cold War not, throughout my childhood, provided Blimpish fools with so many speaking opportunities.

If I find that I still have Degler’s book, I will give it some respectful attention, notwithstanding its lethal subtitle.

***

I’ve been trying to sort out two very tangled but clearly distinct strands of anti-bourgeois passion. The simpler one is the political-philosophical tradition presided over by Karl Marx. (Is it important to know what makes Marxists different from Marxians?) It is easy to see why this adherents of this tradition don’t like the middle classes, and it’s just as easy to see how wrong-headed (because of idealism) their understanding of human nature is. The more complex and far more insidious hatred of the intellectuals is more difficult to grasp. Intellectuals were frequently, perhaps even usually, socialists or communists, but, as John Carey explains in his wonderful study, The Intellectuals and the Masses, they feared and loathed the proletariat. They did not seriously believe that, shackles thrown off, means of production seized, workers would ever understand the superiority of — intellectuals. The intellectuals’ fear and loathing of the bourgeoisie was quite different. Almost all intellectuals, as their mere possession of educations betrayed, sprang from bourgeois origins. This they hastened to conceal with robust denunciations of their roots.

I could have been a classic intellectual. My parents were steady, sensible people (although my mother did have a greater than normal allotment of something that she was always attributing to me, “flair”), while I was a lazy daydreamer who wanted nothing so much as to talk about books. I ought to have grown up full of contempt for my parents’ materialism. Instead, I developed a contempt for the quality of their materialism, which wasn’t very high. They had no interest in fine art — and by fine art, here, I mean the courtly arts of ancien régime Europe. They had no time for history, which, even then, I understood to be the explanation of things, real things in the real world. (Why did practical steam engines first appear in the Eighteenth Century, and not at some other time? For the matter of that, what does “practical” really mean?) I was, in short, a great deal more materialistic than my parents. My critique of their views came, ultimately, from the right, not from the left.

Which made me interested in aristocrats, a category of persons sincerely detested (and, even more, mistrusted) by my Midwestern parents, both of whom had been relocated to the New York area in the Thirties. Aristocrats were, obviously, very interesting. But it was also clear that, as a class, they had failed. It was probably unwise, I concluded, to put so much emphasis on the chances of birth and parentage. So it would be better to say that some aristocrats were interesting — probably not very many. And, then, only at a distance: what made many aristocrats interesting was their terrible behavior. And that shatterproof self-satisfaction! I’ve got a grand example right here. I’m reading Moon Tiger, the Penelope Lively novel that won the Booker Prize in 1987. The title, I fear, is hardly better than The Forces That Shaped Modern America, but the novel is a great read. Here is the protagonist’s mother’s complacent complaint about what her daughter is going to do next:

“Claudia is going to Oxford,” says Mother. “Of course quite a lot of girls do now and she has always been one for getting her own way.” (139)

I barked with laughter when I read it; typing it out just now, I barked again. Mother will be saying next that Claudia is condescending to do Oxford a favor.

A lot of young people, I read, worry during adolescence that they will never grow up and become physically adult — that they will be stuck in an outgrown tail of childhood. What I wondered about was whether I would become an intellectual. First of all, I wasn’t sure that I was smart enough. Oh, I was very smart and all that, but so was everybody else who counted. It was like that line in the episode of Lewis (Season 7, I believe) where the beautiful scientist says, “This is Oxford. We’re all clever.” Beyond that, I felt that I was missing a key component required for the intellectual makeup. It was like worrying about being gay — I was almost certain that I missed this piece of equipment. Or perhaps I had another piece of equipment that would interfere with my becoming an intellectual.

I didn’t know what it was until quite recently — what it was that prevented me from becoming an intellectual. I’ll try to say it as neutrally as possible: I am unable to believe that any idea is more real, more true, or more vigorous than the meanest human being. The attraction of endowing ideals with an overriding significance that is lacking in shambling men and women is clear enough, but so is the horror, especially after the first half of the last century. Equally fraught is the positing of groups and the assignment of membership in those groups to people you don’t really know. The only groups that any of us halfway understand are the groups to which we think we belong, and to the extent that we’re comfortable with those identifications, we ought to regard them as deformations.

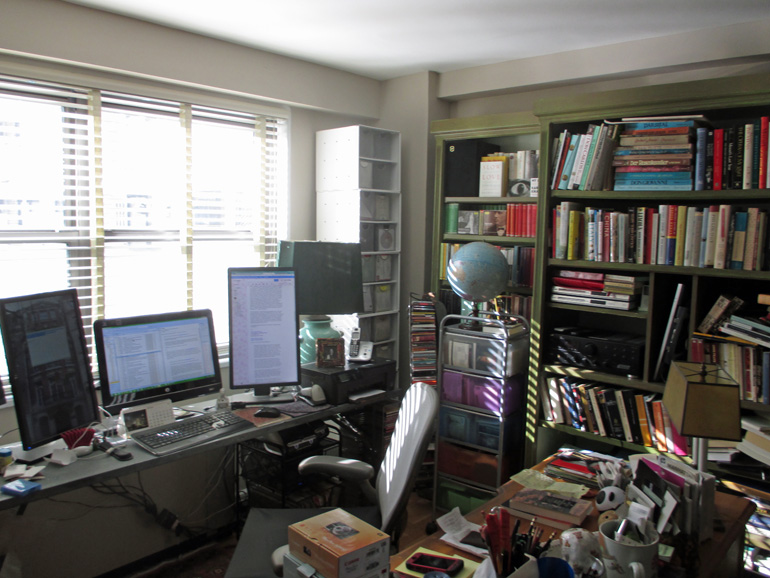

So much for the high-minded angle. I am also too attached to living in clean and comfortable places, surrounded by agreeable objects and regular meals. Too bourgeois.