Matins

¶ Pascal Bruckner’s The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism (translated by Steven Rendall) has just come out in the UK, and it tosses a smart hand grenade into the body of presumptions known in this country as “political correctness.” Eric Kaufmann reviews the book at Prospect. (via  3 Quarks Daily)

Substituting the complex reality of history for victimology, Bruckner’s spade turns up some awkward truths. For instance, there has not been one slave trade, but three: an Arab, an African and a European. The first two were more enduring and trafficked more people than the western variant. The west’s innovation was to end slavery on moral grounds, while it lingered in the Arab world until the 1980s. Despite these inconvenient facts, any questioning of the idea that slavery is a predominantly European crime immediately places one beyond the pale. On this note, Bruckner neatly juxtaposes the tirades of a contemporary professor who urges reparations for slavery from “the Christian nations†with the actual words of Frantz Fanon, the black intellectual whom the reparationists appropriate without a proper reading: “Don’t I have other things to do on this earth than avenge the blacks of the seventeenth century… I am not a slave of the slavery that dehumanised my ancestors.â€

Bruckner seeks a more rounded history. Nations should celebrate their heroes and victories while acknowledging their stains, because there are “no angels and sinners among nations.†In the west, the balance needs to tilt back toward a celebration of achievements and heroes who have fought for freedom and equality. Elsewhere, a little self-criticism would go a long way.

Lauds

¶ At The House Next Door, Tom Elrod goes over the films of Christopher Nolan with an appreciative eye. We hope that the talented director weighs and considers his fan’s astute perception. (By the way, we’d forgotten that the very cool, black-and-white Following is an early Nolan title.)

It comes down to this: Nolan may be not a great storyteller, but he is a great constructer of moments. When Batman first appears in Batman Begins or when Leonard decides to fake evidence that Teddy is his wife’s killer in Memento the “Holy Crap” feeling is genuine. I believe this is what attracts people to Nolan. He plots his films in such a way as to give maximum exposure to the handful of “awesome†moments throughout, allowing them to feel earned in a way they probably aren’t. In an age when Michael Bay can deliver an instinctual or visceral thrill, Nolan offers something just a little bit more: the sense that it’s not all chaos, that the story at least appears to be planned. Thus, when a big moment occurs, you feel the rush of being taken for a ride. It’s not quite the same thing as being told a well-crafted story: almost all of Nolan’s films fall apart or become scrambled at the end. But it’s better than being on a roller coaster with absolutely no sense of direction. In today’s blockbuster environment, that may be enough to turn you into an auteur.

The problem is that as Nolan’s career has progressed, he’s lost sight of how to make those moments feel organic. The moments are there, but how do they connect to the larger film? Nolan’s filmography can perhaps be summed up by the iconic shot of the Joker in The Dark Knight, sticking his head out the police car window, oblivious to the dangers around him—an image of freed chaos. It’s a small, lyrical moment, and it feels like it happened by accident. The shot is surrounded by so much plot detritus that it feels like a scream from a smarter, better film. Alas, such fleeting moments are perhaps the best we can hope for from Christopher Nolan, the plot-master.

Prime

¶ The look of our structural unemployment is beginning to set, and David Leonhardt sketches a few broad outlines. Wages, for those with jobs, are rising, not falling; the states in the dead center of the country, from the Dakotas to Texas, are holding their own (and, aside from Texas, using their enormously leveraged Senatorial power to minimize the expense of aiding the rest of the nation); and this is a white-collar slump. Education is still makes a difference, though; the unemployment rate for college graduates is only 4.5. (NYT)

¶ Of the long-term unemployed, Felix Salmon (back from vacation and most welcome!) writes:

The problem is that persistent unemployment at or around 10% is unacceptable in the U.S., especially with the social safety net being much weaker here than it is in Europe. Leonhardt is right that Euro-style safety nets aren’t particularly innovative, but they do at least keep people housed and clothed and fed and living outside poverty — reasonable expectations for anybody to have, I think, in the richest country in the world. If David Leonhardt can’t think of any bright ideas for solving the persistent-unemployment problem, then the chances are such solutions aren’t going to magically appear. Which means we need to help the long-term unemployed, rather than simply ignore and forget about them.

¶ We’re still pretty new at this, but we’re surprised to see that Tyler Cowen agrees.

Furthermore, I don’t buy the idea that so many of the unemployed are stupidly and stubbornly holding out for a higher wage than they can get, while at the same time they can be reemployed by a mere bit of money illusion. There are so many blog posts written to the Fed, to Bernanke, etc. “Hey guys, goose up the money supply! Bernanke, read your old writings!”Â

Yet I have seen not one such post to the unemployed: “Hey guys, lower your wage demands! It’s good for you! You’ll get a job and avoid the soul-sucking ravages of idleness. It’s good for the country! It’s good for Bernanke, you’ll get those regional Fed presidents off his back! Why not? The best you can hope for is to get tricked by money illusion anyway! Show up those elites and get to that equilibrium on your own! Take control!” and so on. If such posts would seem patently absurd, we should ask what that implies for our underlying theory of current unemployment.

I sooner think of these unemployed individuals as having gone down economic corridors which are no longer promising and not facing any easy adjustment to set things right again.  Furthermore I consider that portrait of their troubles to be more consistent with the general tenor of liberal, left-wing, and progressive thought, not to mention plain common sense.

Tierce

¶ Anchoring update: birds do it, bees do it — sure they do! They must! Because Physarum polycephalum, a brainless, single-celled slime mold, does it! Ed Yong reports, at Not Exactly Rocket Science.

Latty and Beekman did one such test using two food sources – one containing 3% oatmeal and covered in darkness (known as 3D), and another with 5% oatmeal that was brightly lit (5L). Bright light easily damages Physarum, so it had to choose between a heftier but more irritating food source, and a smaller but more pleasant one. With no clear winner, it’s not surprising that the slime mould had no preference – it oozed towards each option just as often as the other.

But things changed when Latty and Beekman added a third option into the mix – a food source containing 1% oatmeal and shrouded in shadow (1D). This third alternative is clearly the inferior one, and Physarum had little time for it. However, its presence changed the mould’s attitude toward the previous two options. Now, 80% of the plasmodia headed towards the 3D source, while around 20% chose the brightly-lit 5L one.

These results strongly suggest that, like humans, Physarum doesn’t attach any intrinsic value to the options that are available to it. Instead, it compares its alternatives. Add something new into the mix, and its decisions change. The presence of the 1D option made the 3D one more attractive by comparison, even though the 3D and 5L alternatives were fundamentally unchanged.

Be sure to click through, to see how it’s done!

Sext

¶ Having read that “local artisanal soda pop is the next hot food trend” (oy!), Chicagoan Claire Zulkey proceeds to palpate the difference that price makes in our moralo-nutritional calculations. (The Awl)

There’s a double standard when it comes to food that’s calorically bad for you. Hell, there’s a double standard even when it comes to food that’s good for you. Those of us who allegedly can afford it and “know better†aren’t supposed to eat baby carrots anymore: we’re supposed to go to the farmers’ market to purchase beautiful fresh-from-the-dirt carrots with green tops, or have them delivered to us in a weekly produce co-op box. You don’t cram them in your face to fill the void and grimly just take it because the food suits its purpose and is filled with these goddamn vitamins and nutrients—you thank Gaia for the soil and the sun that brought it to you and consider yourself one of the “good ones†next time you read a Michael Pollan article.

When it comes to people who live in urban “food deserts†though, we don’t expect that type of worship: they’re lucky to get frozen, even canned, produce. But junk food? That’s when we get snobbish. High-class cupcakes, local pop, hamburgers made by top chefs, these are little indulgences for foodies. But gas-station treats, Coke and Big Macs are part of the nation’s nutrition problem.

Nones

¶ Simon Tisdall’s report on the renewed violence in Kashmir makes us wonder: what if the wealthy nations of the world sat India down and asked what it would take to relinquish its claim on territory inhabited overwhelmingly by Muslims? What would it take? We suspect that the price would not be exorbitant. (Guardian; via Real Clear World)

But Delhi’s blinkered Kashmir policy since partition in 1947 – ignoring UN demands for a self-determination plebiscite, rigging elections, manipulating or overthrowing elected governments, and neglecting economic development – lies at the heart of the problem, according to Barbara Crossette, writing in the Nation.

The violence “is a reminder that many Kashmiris still do not consider themselves part of India and profess that they never will,” she said. “India maintains a force of several hundred thousand troops and paramilitaries in Kashmir, turning the summer capital, Srinagar, into an armed camp frequently under curfew and always under the gun. The media is labouring under severe restrictions. Torture and human rights violations have been well documented.” Comparisons with Israel’s treatment of Palestinians were not inappropriate.

India’s failure to win “hearts and minds” was highlighted by a recent study by Robert Bradnock of Chatham House. It found that 43% of the total adult population of Kashmir, on both sides of the line of control (the unrecognised boundary between Indian and Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir), supported independence for Kashmir while only 21%, nearly all of whom live on the Indian side, wanted to be part of India. Hardly anyone in Jammu and Kashmir wanted to join Pakistan.

Vespers

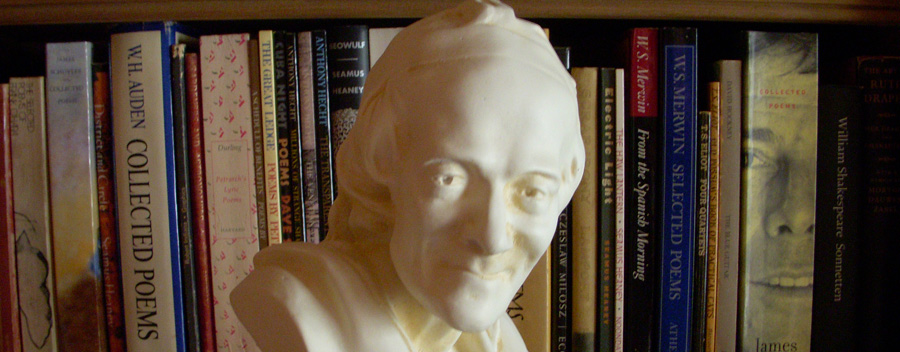

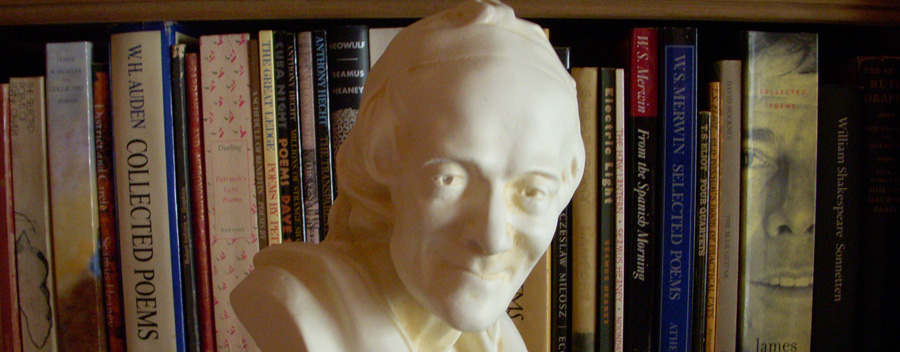

¶ Getting a little ahead of ourselves, we want to talk about a book that the Editor picked up this afternoon at Crawford Doyle, never having heard of it before. It’s Helen Vendler’s Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. The word “magisterial” was invented to describe books such as this one, which will sit very nicely next to Ms Vendler’s edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

So far, there are no online reviews (that we can find), so we’ll have to make do with plush from the publisher, Harvard’s Belknap Press. It’s probably all true, though. If we weren’t so diligent about our duties here, you can bet that we’d be finding out.

In selecting these poems for commentary Vendler chooses to exhibit many aspects of Dickinson’s work as a poet, “from her first-person poems to the poems of grand abstraction, from her ecstatic verses to her unparalleled depictions of emotional numbness, from her comic anecdotes to her painful poems of aftermath.†Included here are many expected favorites as well as more complex and less often anthologized poems. Taken together, Vendler’s selection reveals Emily Dickinson’s development as a poet, her astonishing range, and her revelation of what Wordsworth called “the history and science of feeling.â€

In accompanying commentaries Vendler offers a deeper acquaintance with Dickinson the writer, “the inventive conceiver and linguistic shaper of her perennial themes.â€Â All of Dickinson’s preoccupations—death, religion, love, the natural world, the nature of thought—are explored here in detail, but Vendler always takes care to emphasize the poet’s startling imagination and the ingenuity of her linguistic invention. Whether exploring less familiar poems or favorites we thought we knew, Vendler reveals Dickinson as “a master†of a revolutionary verse-language of immediacy and power. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries will be an indispensable reference work for students of Dickinson and readers of lyric poetry.

Compline

¶ Slow Reading — we know that it’s what this site is all about; but what exactly is it? Forget “exactly.” In a Guardian piece from the middle of last month, Patrick Kingsley pins down some foundational differences of opinion.

“If you want the deep experience of a book, if you want to internalise it, to mix an author’s ideas with your own and make it a more personal experience, you have to read it slowly,” says Ottawa-based John Miedema, author of Slow Reading (2009).

But Lancelot R Fletcher, the first present-day author to popularise the term “slow reading”, disagrees. He argues that slow reading is not so much about unleashing the reader’s creativity, as uncovering the author’s. “My intention was to counter postmodernism, to encourage the discovery of authorial content,” the American expat explains from his holiday in the Caucasus mountains in eastern Europe. “I told my students to believe that the text was written by God – if you can’t understand something written in the text, it’s your fault, not the author’s.”

¶ We’re picking this up now because, yesterday, two blogs that we follow wrote about Slow Reading. At The Neglected Books Page, Brad Bigelow notes that while the environment has changed in a way that may make long-form reading more difficult, it has not changed that much — enough, that is, to render long-form reading redundant.

While I side with Darwin and believe that adaptation to its environment is a species’ greatest survival skill, I also believe that we have a tendency, at least in the U. S., to think that momentum carries us further than is the case. As Timothy Wilson shows in Strangers to Ourselves , when it comes to self-knowledge, we don’t know what we don’t know–but we’re finding out that it’s a whole bunch. So while some of us are Twittering into the future, we are still only a few steps from the cave in much of our unconsciously-driven behavior.

, when it comes to self-knowledge, we don’t know what we don’t know–but we’re finding out that it’s a whole bunch. So while some of us are Twittering into the future, we are still only a few steps from the cave in much of our unconsciously-driven behavior.

And our environment is not changing that quickly, either. Our culture still has strong roots going back thousands of years. Our institutions go back decades and centuries. And our knowledge is still deeply bound to materials, practices, and skills that cannot be mastered in a few clicks. I wouldn’t be too happy to learn that my surgeon earned his license by surfing through “Cardiology for Dummies.†There is a vast amount of information relevant to our world that offers almost nothing of value to a skimmer. I well remember highlighting sentences in my calculus of variations text in college that were grammatically correct and mathematically valid and utterly incomprehensible to a non-mathematician. I’m not sure I could even understand them now, thirty years later. There is no way to unlock material such as this aside from time and close attention.

¶ And Anne Trubek, as a person young enough to have been shaped by environmental changes, is beginning to worry about her reading proficiency.

I have been writing “Signatures,” this column, for almost two years now. Although the title is taken from printing technology, I have always championed digital technologies and gainsaid arguments like Carr’s that would have us believe reading and writing are deteriorating. But I must come clean: I am feeling increasingly worried about my reading capacity. My lifelong habit of reading a book before I fall asleep is turning into a new twitter scrolling habit. I am writing more than I ever have in my life, but I am reading less. I worry.

I still become absorbed in books (Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From The Goon Squad is rocking my world). But my attention wanders more quickly than it used to. Email, texts and, most distressingly, this really stupid Tetris-type game I downloaded onto my iPhone beckon. I am not ready to agree with Carr, but I am ready to take one day off the internet a week. I will turn on the perfectly named Freedom software for my Mac, delete that speed-reading email and hopefully find out how to lose my self again.

¶ It’s customary in these discussions to make some sort of mention, however passing, about the future of books — codices, the things that you buy in a bookstore. In our view, all such talk is rendered moot by Coralie Bickford-Smiths designs for forthcoming Clothbound Classics editions of six Fitzgerald volumes. It’s obvious that, so long as books so lovely are produced, buyers will want them. They may even read them.

Have a Look

¶ Hat tips for ladies and gentlemen. (via  The Morning News)

¶ “Large puter angle – $15.” Now, what do you suppose a large puter angle might be? (You Suck at Craigslist)