As I was tidying the bedroom on Sunday, I had second thoughts about putting a stack of books back on top of a dresser after I’d dusted it. Instead, I carried the pile to the laptop at the dining table, opened Readerware, and used the barcode scanner to autoload the books into the database. When that was done, I bulk edited the lot, assigning each book the same shelf location. Off the top of my head, I chose “Korean” to designate the location; the dresser in question is in the Korean style, or so we were told long ago. Now I have a handy printed list of the sixteen non-fiction titles that spend their time hidden by an array from framed family photographs, waiting for me to read them. At one point, they were all books that I was going to get to “next.”Â

I continued to tidy my way around the bedroom, coming eventually to a pile of books that Kathleen plans to read. I brought this to the laptop computer as well, with “Kathleen’s Reading” as the location. Unlike the “Korean” batch, the books in “Kathleen’s Reading” were in no sense shelved; they were stacked in a pile. There are a number of such piles throughout the apartment, and by the end of the afternoon I had catalogued them all, even the multi-pile aggregation of 61 books located as “NonFiction.”

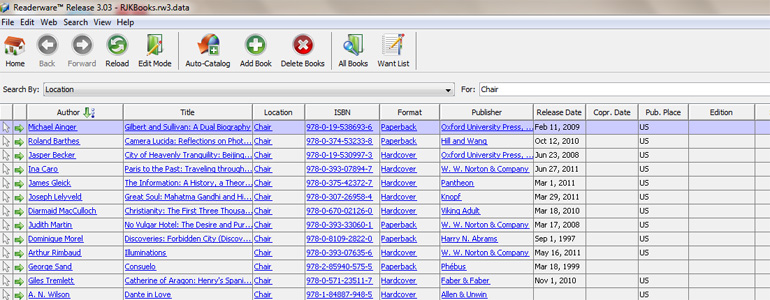

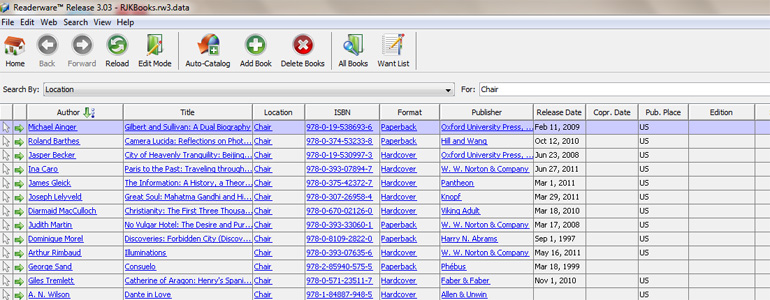

There were three distinct piles of books, “Chevet” (tucked into my nightstand), “Fiction Basket” (a dump in front of my nightstand), and “Fiction Annex,” a small pile in the blue room that didn’t fit anywhere else. The last pile to be catalogued ended up being called “Chair,” because I resolved to stack it in my reading chair whenever I wasn’t sitting there. This has already proved wearisome. It is a very tall stack. Thirteen books, plus a few extras. The extras are Rizzoli’s Treasures of Venice, and the Hallwag map of Venice, both of which are accompanying me through Judith Martin’s No Vulgar Hotel, an extremely amusing book about La Serenissima. No Vulgar Hotel by itself is not a thick book, but it makes a bundle with the guidebook and the map. Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Christianity is in the pile, of course, although I don’t think that it’ll be there much longer, as I am barrelling through the final quarter, my fondness of lingering over the great writing being trumped by the urge to shrink the pile, to which nothing will be added until there are only five books in the lot.

Another book that I hope to speed through is Jasper Becker’s book about Beijing, The City of Heavenly Tranquillity. There’s a Forbidden City guidebook to go with that, too, although I don’t need it anymore, as Becker has moved on to other parts of town. A third entry along these lines is Ina Caro’s delightful Paris to the Past, a sort of souvenir guide to day trips that someone staying in Paris might take to outlying sites of interest, such as Chartres and Malmaison. There’s Michael Ainger’s very good dual biography of Gilbert and Sullivan, and Giles Tremlett’s very something-else biography of Catherine of Aragon. Also Joseph Lelyveld’s book about Gandhi. A N Wilson’s new Dante in Love, which arrived the other day from the UK, went straight into “Chair.” The one book that Readerware’s autoload function detected as already in the database was a thick novel by George Sand that I retrieved from the storage unit last week, Consuelo. I don’t know if it’s any good — and that’s really the appeal. More than 900 pages! There are 105 chapters, plus a conclusion. I read the first one standing in the storage unit, and since I knew all the words I thought I might make a go of it. After all, it is set in Venice in the Eighteenth Century. I’m not sure that I’ll like Sand the novelist, but I already do like Sand the writer.

One book has already been knocked off the list: Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida. It may have been the slimmest book in the title, but it was also the least congenial. Although I can’t say that I found most of it incomprehensible, I did have a strong feeling of in-one-ear-and-out-the-other. It is a very death-haunted book — understandably, if you know the context. (Barthes’s beloved mother had just died, and he was sparked to write about photography in part by a photograph of her as a child in which he felt that he really made her out, the mother he had known as a girl in a winter garden.) I will be on the lookout for temptations to use the terms studium and punctum.Â

At the top of the pile is John Ashbery’s new translation of Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations. I know this prose poem via Benjamin Britten’s (very selective) setting, so it took a moment to find the sung work’s signature line (J’ai seul la clef de cette parade), because it comes after two paragraphs of what Ashbery translates as “Sideshow.” Rimbaud makes Barthes read like a comic book. At the bottom of the pile is James Gleick’s The Information, which I read right up to the penultimate chapter months ago and then set aside, because I wanted to digest the book before I finished it. Even though I’ll finish it soon and find a good place for it in the bookcases, it ought to remain at the bottom of the pile, because it’s what got me to get back to managing my library. I want to own the information. God wot there’s a lot.Â

The most exciting book in the pile, if also the most tiring, is the Ainger, which is really a triple biography of W S Gilbert, Arthur Sullivan — and Richard D’Oyly Carte, the impresario who harnessed the incompatible artists and provided a showcase for their collaboration at the Savoy Theatre. The details are dense, but they don’t obscure the personalities, although poor Helen Lenoir has faded into a translatlantic blur. All sorts of things that I didn’t know: Lewis Carroll approaching Sullivan about adapting Alice for the stage. (Hmmm….) Gilbert’s yachts. Sullivan wading in a creek at Yosemite. I always thought that Sullivan got his knighthood (in 1883) partly so that Victoria could shout “We are not amused” at Gilbert, but this is arrant nonsense, not least because it supposes that the Queen was paying attention to the Savoy operas. Sullivan was by nature an assiduous courtier, and numbered the Duke of Edinburgh among his good friends; one of the fruits of this connection was a Te Deum that Sullivan wrote to celebrate the Prince of Wales’s recovery from typhoid in 1872. That would have endeared him to Her Majesty, the dedicatee.Â

As a reward for all my hard library work, I came down with a cough and a touch of sore throat on Saturday night, and spent the rest of the weekend in a listless state. Reading until I thought that I’d explode with information.Â