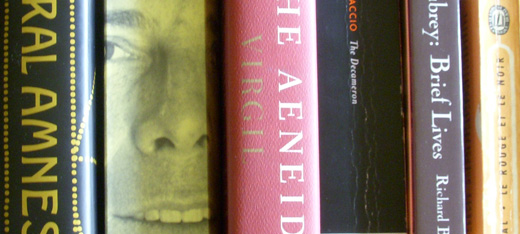

Thursday Morning Read

¶ In the Decameron, a short story between two much longer tales: the improbable, wife-swapping account of Zeppa’s “revenge,” upon discovering that his best friend, Spinelloccio, has been dandling his wife.

Zeppa having consented to this proposal, all four breakfasted together in perfect amity. And from that day forth, each of the ladies had two husbands, and each of the men had two wives, nor did this arrangement give rise to any argument or dispute between them.

What a totally adolescent fantasy.

¶ In the Aeneid, Trojans and Latins bury their dead. This awful line sticks with me:

cetera confusaeque ingentem caedis acervum

nec numero nec honore cremant.

All the rest they burn, unnumbered and unsung,

an enormous tangled mass of bloody carnage waits

Awful, of course, because of more recent horrors.

¶ Some paraphrase of Virgil’s line about confused heaps might be wrought to describe John Aubrey’s prose. It is the language of a man accustomed to leaning on the morphologies of Latin, quite at sea in undeclined Latin, hardly knowing how or where to put the words. Working out the relationships of the six Herberts whom Aubrey writes up would keep me busy for an afternoon, and even then I should be sure that I’d got it right.

Here is a rather elegant example of Aubrey’s distracted prose. Of the widowed, and then twice-married, Mary Sidney, sister of Sir Philip and wife of the Third Earl of Pembroke (a Herbert whom Aubrey did not see fit to commemorate), Aubrey writes,

I think she was buried in the vault in the choir at Salisbury, by Henry Earl of Pembroke, her first husband: but there is no memorial of her, nor of any of the rest except some pennons and escutcheons.

A nice trick, being buried by your late husband. And the “rest” of what?

¶ In Merrill, “Variations and Elegy: White Stag, Black Bear,” dedicated to the poet’s father. Under what circumstances? Illness, perhaps mortal illness, seems to be the gist of the poem, which I find hard to crack, although I like the images of the hunters and the clearings, reminiscent, to me, at least, of the Unicorn tapestries at the Cloisters.

Hunters choke the golden clearing

With apertures: eye, nostril, ear: for there

The white stag prances, unicorn-rare,

Whose hooves since dawn were steeringHis captors toward beatitude;

Yet, when to pouring horns the hunters, nearing

The mound where he should stand subdued,Find once more the shining puzzle

They stalk is constantly disappearing

Beyond the hounds and musket-muzzles,How shall they think that, fearing

He might too blissfully amaze,

The white stag leaps unseen into their gaze,

Into their empty horns, past hearing?

¶ Le rouge et le noir is the strangest novel that I have ever read. As we crawl toward the final pages — Stendhal will stop bothering to give his chapters titles any moment now — Mathilde announces to Julien that she is pregnant with his child, and before we can absorb that bit of news (I must confess, I’d worried), she addresses an astonishingly bold confession to her father. The chapter ends with the very unsurprising news that the marquis is “hors de lui” — beside himself. More anon!

¶ James on Camus: a lovely piece, a gloss on Camus’s line, “Tyrants conduct monologues, above a million solitudes.” The tyrant proves his power, James reminds us, by daring their subjects to betray the tedium of listening to his endless, dreary droning. I’m sure that all the brighter Republicans have spent the last eight years enduring similar torments, but that’s their choice. James does say something wonderfully thoughtful about Camus, though; something to roll around the tongue for a while:

Camus was a bit of an actor — he thought, in fact, that he was a lot of an actor, although his histrionic talent was the weakest item of his theatrical equipment — and, being a bit of an actor, he was preoccupied by questions of authenticity, as truly authentic people seldom are. But under the posturing agonies about authenticity there was something better than authentic: there was something genuine. He was genuinely poetic. Being that, he could apply two tests simultaneously to his own language: the test of expressiveness, and the test of truth to life. To put it another way, he couldn’t not apply them.