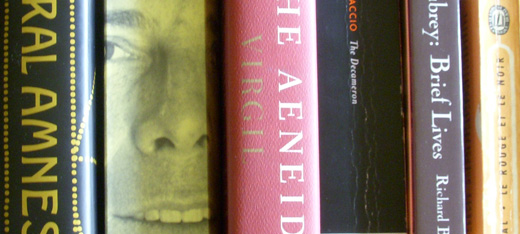

Wednesday Morning Read

¶ In the Decameron, a German soldier living in Milan is outraged when the lady he loves agrees to grant him her favors — for two hundred florins. “Quasi in odio trasmutò il fervente amore.” His scheme to beat her at her own game succeeds. The dishonor of the cuckholded husband is elided entirely, sunk in the “virtue” of the soldier’s trick, which gets him into the lady’s bed quite cost-free.

Is Boccaccio a pagan or a post-Augustinian? Stories such as this one (originally a French fabliau, and retold by Chaucer) make him seem nakedly pagan.

¶ In the Aeneid, Aeneas’ Tuscan fleet lands on the Latian beaches. I wonder if there were any classics scholars at Anzio in 1944, and if they remembered Tarchon’s line:

frangere nec tali puppim statione recuso

arrepte tellure semel.“I don’t flinch from a wreck in such a mooring

Once I’ve seized the land!”

¶ Reading Merrill, I disappoint myself. The verse is so rich that I dread losing hours to poring over it. Then I remember that the idea of the morning read is simply to make sure I know what’s there. “Poem in Spring” recalls Marvell; “Conservatory,” Edith Sitwell. I don’t get much beyond cataloguing the echoes. This image, from “Entrance From Sleep,” sticks:

As dawn to the shade-embroidered fountain brings

The young fern’s wisdom

I’ll figure out what it means when I’m ninety.

¶ In Aubrey: Erasmus, Fairfax, Feriby. Erasmus and Lord Fairfax are of interest to Aubrey primarily as sojourners in Oxford. The item of chief interest in the page on Erasmus is the location of the priest’s rooms at Queen’s College, and a note is appended reporting the Dryden family’s connection to Erasmus. (Ask: did the Darwins marry into the Drydens?) As for Fairfax, this Parliamentary hero (and patron of Marvell) moved quickly to protect the university libraries after the Cavaliers, who according to Aubrey lived up to their name when it came to stealing books, were driven out in 1646.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, more silliness about romance, as Julien follows Korasoff’s advice to the letter. One feels the narrative drive of the earlier chapters about midnight visits to Mathilde, and the like, dissipating with aortal dispatch.

¶ Clive James on Louis Armstrong. And on Bix Biederbecke, and on the folly of the idea that white men can’t riff. (After Biederbecke, whom Armstrong admired, James puts Benny Goodman.) Finally, the piece is about James’s hope that his youthful love of jazz is reflected in his writing. I don’t make out the influence, but I’m glad to read a writer’s claim of musical inspiration.

I went through phases of wishing that I could do with prose what certain composers do with notes, but before proceeding very far down this blind alley I drew the only purposeful lesson, which is to learn to write your own music by listening carefully to your sentences and paragraphs. Even the most powerful metaphor must be well-set.