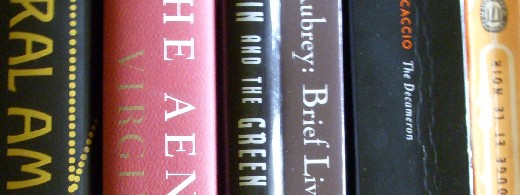

Wednesday Morning Read

¶ Could it be that the reason why Decameron VII, v is not one of the famous ones, even though it is unusually clever and amusing (and that’s saying a lot, considering the company it keeps) is that neither the jealous husband nor his clever wife bears a name? The boy next door is called Filippo, but he is more of an appliance than a character — a tool that the wife uses to get back at the husband. I can’t help thinking that, if it had the handle of distinctive nomenclature, this tale would have inspired several operas. Or at least a play by Goldoni.Â

A wife who is immured in her town house insists upon being allowed to go to Confession on Christmas Day. The jealous husband dons a robe with a big hood and, thinking that he has fooled his wife (who in fact sees through his disguise at once), impersonates the confessor. The wife makes up a story about this priest who can unlock all the doors in her house and who uses this power to visit every night in her bed. The husband, consumed with jealous fury, takes to parking himself just behind the front door, armed to the teeth, waiting to catch the imaginary interloper — while a genuine one, that boy next door, scrambles over the roof for a night of “merriment.” This goes on for a while, until the husband can’t take it any more. Confronting his wife with what she said in confession (“never mind how I know”), he insists that she identify the philandering priest. With all the elegance of the best Italian comedy, the wife tells him that she knew all along that it was he who was pretending to be her confessor, and that the priest whom she referred to, therefore, was none other than her he himself.

¶ In the Aeneid, Euryalus’s mother delivers your standard tirade of grief from the battlements. Then she is comforted by the weeping Trojans. This seems like a nifty occasion for old-master painting, but I don’t remember seeing one. I might have seen twenty, though; my eyes have been glazing over for years at the names of paintings that refer to classical antiquity.

¶ In Aubrey: Chaloner, Chaucer, Chillingworth, Cleveland, Clifford (George), Clifford (Henry), Coke, Colbert, and Colet. Quite a clutch. By no stretch could we say that Aubrey sketches a life of Chaucer; we’re told only that he used to sit under an oak tree the cutting down of which, in the reign of Charles I, led to Star Chamber proceedings. Similarly, the early humanist John Colet, who died in 1519, is mentioned only because his tomb cracked open in the Great Fire of 1666, was found to have been preserved by some sort of “liquor,” the taste of which (!) is described as “insipid.” Colbert — what is Louis XIV’s most able minister doing in these pages? It turns out that he was “of Scottish extraction.” That’s a reach. I read the Life of Sir Edward Coke, having spent many hours with his treatise upon Littleton’s Tenures — a book known to legal historians as “Co.Litt.” The work-in-progress aspect of Brief Lives shines through:

I heard an old lawyer (Dunstable) of the Middle Temple, 1646, who was his countryman, say that he was born but to £300 land per annum, and I have heard some of his country say again that he was born but to £40 per annum. What shall one believe?

Ask Roger Coke at what college he was in Cambridge, or if ever at the University.

“Unibridge” is it, then? Even better: whatever he was born to, Coke died rich.

He left an estate of eleven thousand pounds per annum. Sir John Danvers told me (who knew him) that when one told him his sons would spend the estate faster than he got it, he replied, “They cannot take more delight in spending it than I did in the getting of it.”

Now that’s success!

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, Julien pays another nocturnal visit to Mathilde, this time uninvited. They have a good time, it seems, but Mathilde, who acts very much like the Capucine character in What’s New, Pussycat? seems compelled to put a lid on it whenever she thinks she’s falling in love.

¶ Clive James asks us not to idolize Isoroku Yamamoto (in case we were thinking of doing so). Yamamoto was the diplomat and naval officer who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor — and who knew, according to James, the moment he found out that the American aircraft carriers had been out at sea, that the Japanese cause was doomed. But he was also a gambler… This is a not entirely inapt occasion for James to heap scorn on revisionists who believe that Dropping the Bomb(s) was unnecessary.

I liked this aperçu very much:

Speculations about the subtlety of “the Oriental mind” we can safely discount: they never amount to much more than ignorance and racism snuggling together under a duvet of rhetoric.