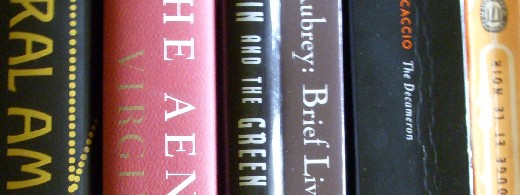

Wednesday Morning Read

As you can tell from the accompanying photo, I’m reading The Aeneid in Robert Fagles’s new rendering(Viking, 2006). But I find that, once I’m tripped into the Loeb Classic text of the original by something or other in the rendering that makes me wonder how Virgil put it, I tend to stay with H R Fairclough’s facing translation (in prose), first published in 1918. This is curious, because all previous attempts to get through the epic by relying on the Loeb edition alone have failed. Â

¶ Tale VII, ii of the Decameron, McWilliam tells us, is taken from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass — a classic that I am going to slip into the Morning Read at the next opportunity. Petronella hides her boyfriend in a tub, and then tries to pass him off to her husband as one who would purchase the tub (for seven ducats) if only it were really spic and span; whilst the husband scrubs the tub, the boyfriend takes his mistress “like a Parthian mare.” Very earthy.

My favorite version of this story is Ravel’s little opera L’heure espagnole. There is no Parthian-mare business, of course, and the husband is offstage for most of the fun, but the mule-driver, Ramiro, who comes in to get his, er, clock cleaned, certainly makes with the biceps while carrying case-clocks up and down the stairs — clocks in which the watchmaker’s wife, Concepcion (!) has concealed her admirers! Ramiro’s watch, we’re told right up front, belonged to his uncle, a toreador… Concepcion soon decides that she prefers what she can see to what she has hidden.

¶ In the Aeneid, Nisus and Euryalus, whom we last saw at Anchises’ funeral games in Book V, come up with a scheme for getting round the encircling Rutulians. Aletes, “bowed with the years, a seasoned advisers,” offers up thanks to the gods for having put “such courage, such resolve in our young soldiers’ hearts. Exciting stuff.

There is another one of those night scenes that Virgil is so fond of, where he varies, but only slightly, his formula of placing a background of sleeping beasts and men behind diligent plotters. This time, the setting is laid out in two lines:

Cetera per terras omnia animalia somno

laxabant curas et corda oblita laborum:

Because Virgil always sounds vaguely like a doctor when he gently extols the benefits of sleep, this sort of thing always makes me wonder if Virgil was an insomniac, or perhaps an inveterate napper.Â

¶ In Aubrey: Bovey, Boyle (Richard, the Earl of Cork and father of), Boyle (Robert, promulgator of the famous law), Brereton, Brerewood, Briggs, Broughton (Elizabeth — the first woman), Brouncker, Bulkeley, and Burton. Perhaps because I’m a lawyer, I find the Life of Bovey arresting at every turn. Having made his pile in business, and written a treatise on the art of the deal, Negotiative Philosophy, Bovey went in to the Inner Temple, where “his judgment has been taken in most of the great causes of hi time in points concerning the merchant law.”

His whole life has been perplexed by law-suits (which ha made him expert in human affairs), in which he always overcame. He had many lawsuits with powerful adversaries; one lasted 18 years. Red-haired men never had any kindness for him. He used to say “Beneath a red head there is never a mind without malice.” In all his travels he was never robbed.

— despite his height of four feet. The sheer miscellaneousness of Aubrey’s style works exuberantly here.

He has one son, and one daughter, who resembles him. From 14 he began to take notice of all the rules for prudent conduct that came his way, and wrote them down, and so continued to this day, September 28, 1680, being now in his 59th year. As to his health, he never had it very well, but indifferently, always a weak stomach, which proceeded from the agitation of the brain. His diet was always fine diet: much chicken.

There you have it. Edward Brereton’s edifying story has no doubt appealed to generations of varsity men’s fathers:

My old cousin Whitney, a fellow there long since, told me, as I remember, that his father was a citizen of West Chester; that (I have now forgotten on what occasion, whether he had run through his allowance from his father, or what) but he was for some time in straits in the College: that he went not out of the College gates in a good while, nor (I think), out of his chamber, but was in slippers, and wore out his gown and clothes on the board and benches of his chamber, but profited in knowledge wonderfully.

¶ In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, we have the second day of what appears to be Gawain’s ordeal: resisting the blandishments of the lady of the castle. On the first night, when he and the lord shared their day’s respective hauls, Gawain got several sides of venison, and gave a goodly kiss. On the second night, he got a boar, and kissed the lord twice. You begin to get the picture of where any serious hanky-panky with the lady might lead.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, the most gloriously funny anticlimax in literature. Julien climbs the ladder in the moonlight, and Mathilde helps him into her room. Now what? The two young people have been so preoccupied by the minute steps of their illicit epistolary conversation that they haven’t given much thought to its object. Alone in her room with the ill-born seminarian, Mathilde is appalled by her indiscretion, especially when he crows about the pains that he has taken to protect himself from the servants and Mathilde’s brother (in case she advised them of the rendez-vous — an ambitious man, he worries much more about being made a fool of than about amorous unhappiness). Julien spends the night in an armoire; while, for her part, Mathilde, disappointed that the night failed to bring her “cette entière félicité dont parlent les romans,” decides that she’s not in love with Julien after all.

¶ Writing about Mario Vargas Llosa, Clive James pretty much sticks to his subject for a change. It must be said that James’s tireless advocacy of reading foreign languages (which ought to be perfectly unnecessary) gives him great stature in my eyes. He always gets far beyond the “it’s good for you” stage, and arrives at an indisputable benefit.

One of the many advantages of learning to read Spanish is that a copiously productive writer like Vargas Llosa, who responds to current history, can be read while the history is still current. Despite the turmoil, the anguish and the frequent desperation of his raw material, a Spanish word, hechiceria (witchcraft, charm), and a Spanish phrase, a sus anchas (at one’s ease), both apply exactly to his prose, one of the more encouraging continuities linking two millennia.