Monday Morning Read

“Afternoon Read” would be more like it, today — although I did read almost everything before noon. Â

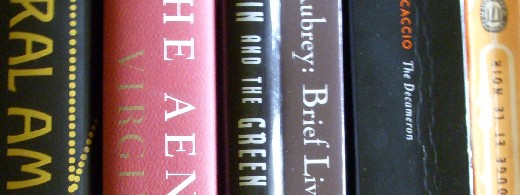

¶ With only three tales left — and only the last of them any longer than the Day’s other anecdotes — I decided to plow through the rest if the Sixth Day in one go. In VI, viii, a father has the doubtful pleasure of advising his daughter not to look in a mirror if she is really as tired of “horrid people” as she complains of being; and in VI, ix, Guido de’ Cavalcanti makes his celebrated riposte to fellows who would “torment” him in a graveyard: “Gentlemen, in your own house you may say whatever you like to me.”

Leave it to Dioneo, who always has to be different (when he’s not being dirty), to invert the day’s formula: whereas all the earlier tales turned on one-liners, Dioneo’s tale of Fra Cipolla runs into overtime as the friar, having been fooled by two amigos, delivers an ex tempore Clarence Darrow, full of nonsense about such “countries” as the Kingdom of Algebra and such “marvels” as the fact that the water in Basque country flows downhill, while trying to invent a plausible explanation for the “transformation” of the Angel Gabriel’s feather (plucked from a parrot, Boccaccio shamelessly tell us) into lumps of coal. Aha! The coals are relics of San Lorenzo’s martyrdom.

In the afternoon and evening, everyone goes skinnydipping in the Valley of the Ladies, although not (peris the thought!) in mixed company.

¶ Book Nine of the Aeneid begins the outbreak of war. Things go badly for King Turnus. We’re given a long just-so story that explains why the Trojan fleet — or what was left of it — was non-flammable. The sources of the River Ganges are alluded to.

¶ Aubrey’s Life of Francis Bacon is a shambles, given over to a description of the already-demolished Verulam House, Bacon’s retreat at Gorhambury. Much more appealing is the account of Isaac Barrow (1630-1677), an absent-minded scholar whom everybody seems to have liked and wanted to help — owing to the Civil War, the young man was usually out of funds. Barrow appears to have died of an overdose of opium, a habit that he picked up in Istanbul.

As he lay expiring in the agony of death, the standers-by could hear him say softly “I have seen the glories of the world.”

The Bacon piece, though, contains this truly startling statement (immediately qualified in terms that we might find somewhat irrelevant but that certainly weren’t in Aubrey’s day):

He was a homosexual*. His Ganymedes and favourites took bribes; but his lordship always gave e judgment according to justice and honesty. His decrees in Chancery stand firm, i e there are fewer of his decrees reversed than of any other chancellor.

¶ The second half of the Second Fitt of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight works its way somewhat laboriously — or, it may be, parenthetically — to a deal that the master of the castle offers to Gawain, who by now is much taken with the master’s lady. (And why not? She’s fairer still than Guinevere!) The master will go hunting on the morrow, while Gawain will keep to the castle. At the end of the day, they will swap “quat-so-ever” they “wynne.” Goosebumps!

¶ Temperatures rise in Le rouge et le noir, as Mathilde and Julien conduct their “roman par lettres.” The chapter’s ending is such that we may wonder whether we’re reading one of the great romantic novels or a burlesque of Tom Brown’s School Days.

A cinq heures, Julien reçut une troisième lettre; elle lui fut lancée de la porte de la bibliothèque. Mademoiselle de La Mole s’enfuit encore. Quelle manie d’eécrire! se dit-il en riant, quand on peut se parler si commodément. L’ennemi veut avoir de mes lettres, c’est clair, et des phrases élégantes, pensait-il; mail il pâlit en lisant. It n’y avait que huit lignes:

J’ai besoin de vous parler: il faut que je vous parles ce soir; au moment où une heure après minuit sonnera, trouvez-vous dans le jardin. Prenez la grande échelle du jardinier près du puits; placez-la contre ma fenêtre et montez chez moi. Il fait clair de lune: n’importe.

¶ The text for Clive James’s sermon today is a quotation of one writer (Pedro Heriquez Ureña, James’s nominal subject) by another (Ernesto Sabato): “Great art beings where grammar ends.” In other words, you have to know the rules before you can break them. If I learned nothing else in school, I did learn this, and experience has never stopped providing me with fresh examples. James’s dismissal of “unschooled genius” is almost artlessly straightforward.

There is a consoling mythology, constantly being added to, which would have us believe that genius operates beyond donkey work. Thus we are told reassuringly that Einstein was no better at arithmetic than we are; that Mozart gaily broke the rules of composition while jotting down a stream of black dots without even looking; and that Shakespeare didn’t care about grammar. Superficially, there are facts to lend substance to these illusions. But illusions they remain. There is always some autistic child in India who can speak in prime numbers, but that doesn’t mean that Einstein couldn’t add up; Mozart would not have been able to break the rules in an interesting way unless he was able to keep them if required; and Shakespeare, far from being careless about grammar, could depart from it in any direction only because he had first mastered it as a structure.