Monday Morning Read

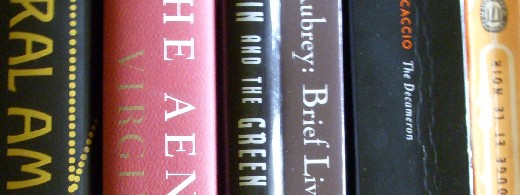

Monday Housekeeping Note: Two new books join the list today. That’s probably not a very good idea, because I often have barely enough time to get through four books, and six will be quite a load; but it’s early days at this enterprise, and we’ll see how it goes. The two new books are John Aubrey’s Brief Lives and the anonymous medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in a new translation by Simon Armitage.

Brief Lives is a title that I recall running into all the time in my student days, but I don’t think I’d ever seen a copy until one arrived in the mail a few weeks ago. Richard Barber’s edition dates back to 1982, but my Boydell reprint appeared in 2004. It turns out to be a more curious book than I expected. Indeed, its contents are more “construct” than “book.”

It might seem imbalanced to introduce one epic poem in the middle of reading another, but Sir Gawain does not appear here qua epic poem, in any kind of competition with the Aeneid. It is rather the book of English verse du jour. It very nicely follows on Seamus Heaney’s District and Circle. Mr Heaney, of course, is the most recent notable translator of Beowulf, and Mr Armitage hails it as one of the “gateposts” on the way to his own work.

¶ We have a star turn in the Decameron today: Giotto himself makes an appearance. Yes, the famous artist. (I told you that Today is topical!) Witty but apparently not very good-looking, he gets in a good one, when his companion on a mud-soaked slog from the country back into Florence — a jurist who’s just as ugly, it seems — takes a look at him and laughs. “Who, seeing you now, would imagine that you’re the greatest painter of the day?” “Anyone at all, once they’d learned that you know the alphabet.”

¶ In the Aeneid, Venus cajoles Vulcan into making a shield for Aeneas — pointing out that she hasn’t asked for anything on behalf of the Trojans before. Of course the formerly unhappy couple have to have a tumble before he’ll get to work. What is it about Latin that makes sex so smirky?

ea verba locutus

optatos dedit amplexus placidumque petivit

conjugis infusus gremio per membra soporem.

Translation upon request; “amplexus placidumque” indeed!

¶ Richard Barber’s edition of Brief Lives begins with John Aubrey’s autobiography, the last thing that Aubrey would have started it with, had he ever actually made a book of his scraps, which, Barber tells us, would be better entitled Notes on the Lives of Eminent Men, as a contribution to Mr Wood’s Athenae Oxonienses. “Notes” gets what we have here exactly right.

What did I do that was worthy, leading this kind of life? Truly nothing; only shadows, that is. Osney abbey ruins, etc, antiquities. A whetstone, itself incapable of cutting, e g my universal character. That which was neglected and quite forgotten and had sunk had not I engaged in the work, to carry on the work, name them.

Notes toward notes, perhaps. My favorite paragraph, which repeats much of the above but in a compressed form that resists comprehension like a horse that won’t be patted, here entire:

Real character, that lay dead, antiquities, I caused to revive by engaging six or seven? to record them. I busied myself as a whetstone etc.

The whetstone is a reference to Horace’s Ars Poetica. I don’t know when Horace came to be established as the English gentleman’s favorite poet, but it was well before Aubrey’s day. So marinated in Horace were all the better Brits that the Roman poet might claim to have been the first Whig. (Whether from analphabetism or some other cause, Tories don’t read.)

¶ One antiquity that Aubrey might conceivably have seen was the manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which had surfaced at the beginning of the Seventeenth Century and passed into the still-celebrated library of Sir Robert Cotton. By Aubrey’s day, however, the library, a target of Stuart disapproval, had been confiscated by the Crown and then returned to Cotton’s heirs. Sir Gawain would not be rediscovered for good until the Nineteenth Century.

Composed around 1400, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight hearkens back to an older world just as strenuously as the Decameron seems to look forward to a new one. At the same time, the poem is sempiternally English. What could be a thicker slice of Old Etonian roast beef than this:

It was Christmas at Camelot — King Arthur’s court,

where the great and the good of the land had gathered,

all the righteous lords of the ranks of the Round Table

quite properly carousing and reveling in pleasure.

Time after time, in tournaments of joust,

they had lunged at each other with leveled lances

then returned to the castle to carry on their caroling,

for the feasting lasted a full fortnight and one day,

with more food and drink than a fellow could dream of.

My Middle English isn’t exactly fluent, but the original text on the facing page appears fairly consonant with Simon Armitage’s translation.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, we see the romantic project — as it must be called — from Mathilde’s point of view.

Elle repassa dans sa tête toutes les descriptions de passion qu’elle avait lues dans Manon Lescaut, la Nouvelle Héloïse, les Lettres d’une Religieuse portugaise, etc etc. Il n’était question, bien entendu, que de la grande passion; l’amour léger était indigne d’une fille de son âge et de sa naissance. Elle ne donnait le nom d’amour qu’à ce sentiment héroique que l’on rencontrait en france du temps de Henri III et de Bassompierre. Cet amour-là ne cédait point bassement aux obstacles; mais, bien loin de là , faisait faire de grandes choses. Quel malheur pour moi qu’il n’y ait pas une cour véritable comme celle de Catherine de Médicis ou de Louis XIII! Je me sens au niveau de tout ce qu’il y a de plus hardi et de plus grand. Que ne ferais-je pas d’un roi homme de coeur, comme Louis XIII, soupirant à mes pieds! Je le mènerais en Vendée comme dit si souvent le baron de Tolly, et de là il reconquerrait son royaume; alors plus de charte… et Julien me seconderait. Que lui manque-t-il? un nom et de la fortune. Il se ferait un nom, il acquerrait de la fortune.

Just so. D’you think Keira Knightley speaks French?

I wish I could find that quote that I’ve always attributed to Stendhal: no one would fall in love without reading about it first. In today’s entertainment-saturated atmosphere, who can guess the truth of such an observation?

¶ Clives James’s piece, nominally on Karl Tschuppik, a Weimar historian of “the old k u k society,” displays an amiable valetudinarian’s wandering spread. An old fashioned chapter-heading synopsis might read:

Tschuppik — Austrian book production in the earlier Twentieth Century — Castolovice (Bohemia) — The Dual Monarchy — Metternich’s Denkwürdigkeiten — Metternich’s reactionary views — mistrust of wit, especially in women — Germaine de Staël — the Velvet Revolution — the restoration of Czech cultural heritage — the pleasures of Castolovice — the Olomouc Festival of Documentary Film — learning Czech (proposed)

It’s almost like a trip back to the good old days — for those who could expect to sleep in chambers similar to the Sternbergs’, if not for those who might have waited upon them. There is an old-world luxuriousness in James’s dream of learning Czech. Here he is, admiring books by Masaryk and BeneÅ¡:

I did everything but read them. I can’t read Czech: not yet, anyway. I am told that once you master the alphabet it is not as hard as Russian. It is certainly easier than Polish to pronounce. The prose of BeneÅ¡ is famously unreadable but I would like to be able to judge that for myself, and Masaryk was such a man as few countries are given for a spiritual father: I would like to relish what he wrote in the way he wrote it. If I had the knack of Timothy Garton-Ash, I would be reading it by now. Those of us with more pedestrian powers of assimilation have to find the time, and at my age I am feeling a bit short of time altogether. But the books will go into my shelves anyway, where one day, if my library stays together, someone like me might come along and take them down — I hope without having to brush them free of cement dust, or whatever residue might characterize the next barbaric age.