Morning Read

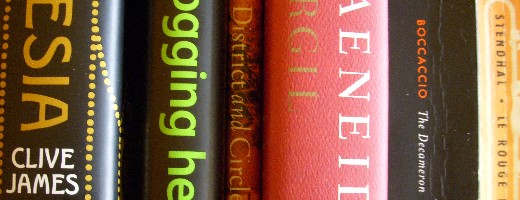

¶ And so the Fifth Day comes to an end, in the Decameron — with a tale about a “cattivo marito.” How things have changed. Today, the misery endured by heterogeneric couples whose marriage would never have occurred had the homosexual partner been allowed to marry someone of the same sex is put forth as as a plank in the platform of gay marriage, and I’ve no bone to pick with that. For Boccaccio, things are different — and rather merrier.

Dopo la cena, quello che Pietro si divisasse a sodisfacimento di tutti e tre, m’è uscito di mente; so io ben cotanto, che la mattina vegnente infino in su la piazza fu il giovane, non assai certo qual più stato si fosse la notte o moglie o marito, accompagnato.

How exactly Pietro arranged matters, after supper, to the mutual satisfaction of all three parties, I no longer remember. But I do know that the young man was found next morning wandering about the piazza, not exactly certain with which of the pair he had spent the greater part of the night, the wife or the husband.

One wonder what would become of humanist liberal arts education if students were to ponder, alongside the Categorical Imperative and other philosophical lodestones, the maxim, “Don’t Get Caught.”

I must say that I protest McWilliam’s translation of “cattivo” as “degenerate”; it’s an unpleasant way of communicating Boccaccio’s evasion of the S word (for “sodomy,” as homosexual sex used to be called). “Naughty” or, at the very most, “wicked” would have been preferable.

¶ In the Aeneid, a rather pleasant surprise: the opening lines of Book Eight bring to mind the current exhibition, Poussin and Nature, at the Museum.

The dead of night.

Over the earth all weary living things, all birds and flocks

Were fast asleep when captain Aeneas, his heart racked

by the threat of war, lay down on a bank beneath

the chilly arc of the sky and at long last

indulged his limbs in sleep. Before his eyes

the god of the lovely river, old Tiber himself,

seemed to rise from among the poplar leaves,

gowned in his blue-grey linen fine as mist

with a shady crown of reeds to wreathe his hair,

and greeted Aeneas to ease him of his anguish.…

“I am the flowing river that you see, sweeping the banks

and cutting across the tilled fields rich and green.

I am the river Tiber. Clear blue as the heavens,

stream most loved by the gods who rule the sky.

My great home is here,

my fountainhead gives rise to noble cities.”

¶ A really rather funny chapter in Le rouge et le noir. Julien is accosted by a man in a café; the memory of an earlier, similar slight impels our hero to demand satisfaction. It turns out that the assailant is the coachman of an aristocratic and very elegant diplomat.

Sa physionomie, noble et vide, annonçait des idées convenables et rares: l’idéal de l’homme aimable, l’horreur de l’imprévu et de la plaisanterie, beaucoup de gravité.

This sort of gentleman, whose ideas are both rare and conventional, hasn’t been given enough attention in Anglophone fiction. We associate the conventional with the fussily anxious. The Chevalier de Beauvoisis, in contrast, is impassively ordinary. Not at all an uncommon type here on the Upper East Side. Like the chevalier, such men (and women) are usually attractive, in a bland sort of way. I don’t mean “handsome” or even “good-looking”; I mean attractive: they attract one’s credulity.

Julien and the diplomat have their perfectly unnecessary duel; Julien takes a bullet in his arm. Having inquired into his challenger’s identity, the appalled chevalier puts it about that Julien is really the bastard of a Franche-Comtéan eminence. Happily, the Marquis de La Mole doesn’t mind this at all. On the contrary, he instructs Julien to hang out at the Opéra, to get to know famous people by sight as well as to shake off some of his remaining façons de province. Â

¶ Clive James on Manès Sperber, of whom I hadn’t heard before. A communist in his youth who found sanctuary in Switzerland, Sperber never quite — to James’s satisfaction, at least — acknowledged that denying the extremes of both communism and fascism is nonetheless a viable political position. But at least Sperber acknowledged that he’d been wrong — to the point of bad faith — about communism.

If I look carefully at my own memories, many of them centre on the humiliating moment when shabby behaviour was observed and correctly judged by someone else whose face I still recall exactly, and for no other reason. Other people tell me that the same is true for them. If there is such an automatic and unceasing system of moral accountancy in the mind, Sperber was one of its first scholarly explorers, although of course it had been explored in literature from the beginning. Shakespeare’s ghosts are memories that haunt living minds. Tolstoy is full of such moments. When we read his biography, his egocentricity seems monstrous. But when we read him, we see that his soul was examining its memories constantly, and assessing them according to a moral test. When, in War and Peace, Zherkovim makes a condescending joke about General Mack and is chewed out by Andrey, why is Zherkovim’s humiliation so vividly presented? Almost certainly because it happened to Tolstoy himself. He was laying a ghost to rest. The conspicuous merit of Sperber’s great work is that these admissions about the mind’s embarrassments are not offset on to fictional characters, but are faced fair and square as personal experience.

That’s yet another passage that, by itself, is worth the price of James’s book.

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero (only three more to go): Eric T, of Internet Duct Tape (a site that, designed for Firefox, looks quite awful on Internet Explorer). It would be grotesquely unfair to suggest that nobody in this wretched book has anything useful to say, but I haven’t exactly harvested it for gems. Eric T, however, speaks directly to me in two passages. First: “The best way to learn something is to share the information with other people.” I couldn’t agree more. Experience has taken my natural inclination toward generosity and made a real policy out of it. Then, about blogging:

Q You’ve made the Technorati list twice. You’ve helped hundreds, if not thousands, of people. You’ve learned a lot and had some fun. [See what I mean about “wretched’?] Based on your experiences, what advice can you offer?

A Know what you want to get out of it. That sounds very glib and simple, but knowing what you want to get out of it is actually the hardest question, and something you should ask yourself repeatedly every few months or so. Is this what I want to get out of it? It’s a huge time sink. What are you doing it for? Are you doing it to build an online entity? Are you doing it to create opportunities and connections with other things? Are you doing it to make money online? Purely for fun?

Or perhaps to do what you were meant to do. I don’t ask about what it is that I want to get out of The Daily Blague; I’m more concerned with what readers might. Therefore it’s a question of what I’m putting into it, and that is indeed a question that I hope I would entertain regularly if it did not very pungently force itself upon me at least once a year. Just about a year ago, I decided that I wanted a new look for the blog, with a new platform and a new server host. No sooner had that been accomplished, in August, than I embarked on a number of other experiments, involving such things as PodCasting and voice-activated software (and the peculiarly Manhattanite problem of setting up reliable Wi-Fi reception within the apartment). And just about a month ago, my impatience with learning curves crashed on the realization that I wasn’t paying very much attention to “content.” (That’s to say that I was simply turning out “content” by the yard.) So I’ve gone back to basics for the time being and re-framed my answer to Eric T’s question.

The year of technological buccaneering wasn’t at all a waste of time. The things that I learned informed my renewed sense of “the basics.” It established frontiers within which I can play and grow, even if, on the surface, it appears that I’m working very hard.