Morning Read

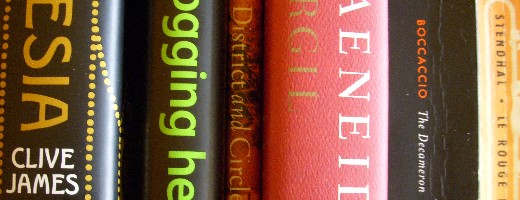

¶ In Decameron V, ix, we have an ancestor of O Henry’s most famous story, “The Gift of the Magi.” A lover, with nothing else to offer his “cruel” beloved, slaughters a prized falcon and serves it to her for lunch. Guess what! Her dying son had his heart set on playing with this very bird, and the lady is only visiting her hapless admirer in order to ask him to take pity on her boy — even though she knows that she has no right to ask. But first — before etiquette permits her to frame her request — a little fricassee.

They say that the old stories are eternal. Some are indeed very old, but this tale suggests the very opposite: that stories undergo incessant refinement, sharpening edges and gentling contours to suit increasingly sophisticated — jaded? — listeners. Boccaccio’s version is, by any modern editorial standards, a mess. But if it fails to please as entertainment, it provides the enormous interest of the forerunner. Literary texts are one of the very few forms of culture that survive intact.

¶ In the Aeneid, I push through to the end of Book VII, a long parade of the Italian foes who line up to fight the Trojans. This is the sort of thing that bores schoolboys to tears but that rings with interest for the older reader, who is sure to have come across this or that name somewhere along life’s pathway. Virgil tucks in an interesting fable about Hippolytus, the object of Phaedra’s depraved affections, according to which he is brought back to life from his seaside smashup under the unprepossessing, perhaps excessively masculine name of Virbius.

¶ A short chapter of Le rouge and le noir makes me wonder just how impromptu or off-the-cuff the writing of this novel might have been. Entitled “La Sensibilité et une Grande Dame Dévote,” the chapter doesn’t get round to the grand dame, Mme de La Mole, until the final paragraph, where another new character, the Baron de La Joumate, is somewhat inconsequently introduced.

By now, the reader knows Julien well enough to appreciate how characteristic and yet how funny the following snapshot is.

Dès qu’il pouvait disposer d’un instant, au lieu de l’employer à lire comme autrefois, il courait au manège et demandait les chevaux les plus vicieux. Dans les promenades avec le maître du manège, il était presque régulièrement jeté par terre.

¶ Clive James on Wolf Jobst Siedler, a German writer and publisher whom I’d never heard of, but whom James accuses of “normalizing” the Third Reich.

Siedler has done us a service by bringing out the cosiness that the Nazis offered the middle class in return for its quiescence. He could have done more to bring out the Nazis’ cleverness in offering the lower orders, set free to climb by the radical social programmes, a point of aspiration that would recompense them for any horrors they might have to endure or inflict: membership of the middle class. But what he scarcely brings out at all is that nobody with half a brain, whether the brain was bourgeois or plebeian, could have failed to notice for five minutes that the whole Nazi state was a raving madhouse.

Hmm. Not sure that I don’t incline toward Siedler here. By any objective account, the Bush America that I live in is, if not a raving madhouse, then perhaps a catatonic one, but we do our best to act as though all were well.

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero: Richard MacManus, of Read/WriteWeb. If I were a scholar, or perhaps a masochist, I’d try to learn something from this blog. A quick look at one of the recent entries — devoted to a recent speech given by Tim Berners-Lee, who, you know, invented the, you know what — I come across the following:

My standard explanation of the value of the Semantic Web is this:

Once our software is capable of deriving meaning from web pages it looks at for us, then there’s a whole lot of work that will already be done, allowing our human, creative minds to reach new heights.

I don’t know whether to laugh, cry, or read further. The “Semantic Web”? Holy Mother of Multitasking!