Morning Read

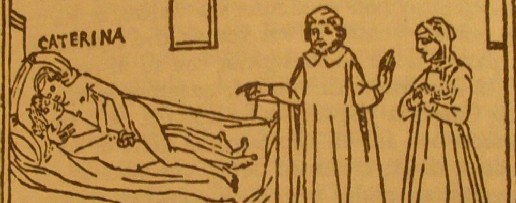

Today, we have a dirty picture! I had to photograph it, because the scanner, while perfectly fuctional, won’t hook up with the computer at the moment. Yes, there’s another scanner (the very same model) in the bedroom, but to use it I’d have to boot up the laptop, and then cope with the Wi-Fi signal, which might or might not be registering… I am very anti-tech at the moment.

But even if you don’t ordinarily follow this feature, be sure not to miss the salacious woodcut from a Venetian Decameron of 1492.

¶ The Decameron, V, iv: the tale of the “nightingale.” Not so much a story as a teenager’s smutty joke. In this comedy of Romeo and Juliet, as it were, Caterina begs to be allowed to sleep on the balcony, where the fresh air and the song of the nightingale will help her to sleep. Ahem! Ricciardo scales the wall and, together, they spend a night of love — molte volte faccendo cantar l’usignolo. Caterina falls asleep with her hands cupping Ricciardo’s privates — ahem! — and in the morning, when her father discovers the happy pair, he rushes off to his wife.

“Be quick, woman, get up and come and see, for your daughter was so fascinated by the nightingale that she succeeded in waylaying it, and is holding it in her hand.”

There’s a happy ending, of course — and no end of “nightingales.” The word is inserted at every opportunity.

They say that a picture is worth a thousand words, but this little woodcut, from the 1492 edition of the Decameron (from my very inexpensive Italian text) suggests that the reverse might, upon occasion, be true.

¶ The second half of the Aeneid is its business end. Having traveled about and dallied with Dido in the first half, Aeneas must buckle down now to the task of colonizing Rome. Curiously, there is something about the welcome that he receives from King Latinus (who has been told in visions that his country’s future lies with foreigners) makes me think of the welcome with which European imperialists were so often received, thousands of years later. Thousands of years and thousands of readings of this text, which, unlike Homer’s epics, which were unavailable for many centuries, carried the glories of the ancient world into the Dark and Middle Ages.

I also wondered, for the very first time, just how much of all this Virgil made up. One imagines that Homer believed that the events of which he sang had actually occurred, but one can’t think the same of the Roman poet.

¶ The last poem in District and Circle, “The Blackbird of Glanmore,” sticks with me even though I don’t quite get it. There has been an accident, and it would seem that the blackbird is shot later, as if for having been a harbinger. For most of the short poem, though, the bird is a domestic familiar who welcomes the poet upon his return home, “My homesick first term over.” The last two lines repeat the first and last lines of the first stanza:

Hedge-hop, I am absolute

For you, your ready talkback,

Your each stand-offish comeback.

Your picky, nervy goldbeak —

On the grass when I arrive,In the ivy when I leave.

Â

¶ Clive James is so done with José Saramago when he’s through that I’m ready to crate up the three or four unread volumes of the Portuguese Nobelist and ship them off somewhere.

Europe might have taught him Euroscepticism. There was a whole ruined world that should have taught him about communism. He never got the point. As a diehard believer who had refused to give up his faith in the face of limitless evidence that it was a pack of lies whose first victims were the people it claimed to benefit, Saramago was reminiscent of Pablo Neruda and Nicolás Guillén: he had to be taken seriously because there was no other way to take him.

Of course this sort of things makes me worry a bit that James is a crypto-neoconservative. It’s important not to let one’s contempt for communism carry one away: too many babies have been thrown out with that bathwater. It is one thing to say that communism is wrong because it oppresses the human spirit, and quite another to say — as I fear most God-fearing capitalists have said — that it is bad because it is communism. The worst thing about communism, from an intellectual standpoint, is that it’s a really lousy critique of capitalism. But the children of Hegel, while alert to the owl of Minerva, are too rarely sensible of the dart of Eros.

¶ Le rouge et le noir, Part II. Julien in Paris: Abbé Pirard tells him what to expect as a secretary in the de La Mole household.

Avec ce je ne sais quoi d’indéfinissable, du moins pour moi, qu’il y a dans votre caractère, si vous ne faites pas fortune vous serez persécuté; il n’y a pas de moyen terme pour vous. Ne vous abusez pas. Les hommes voient qu’ils ne vous font plaisir en vous addressant la parole; dans un pays social comme celui-ci, vous êtes voué au malheur si vous n’arrivez pas axu respects.

And because of that — at least, to me — inexplicable quality you have in your make-up, if you aren’t a success you’ll be persecuted; there’s no middle way for you. Make no mistake. People see that it gives you no pleasure when they address you; in a social nation like this one you’re bound to suffer if you don’t command respect. (Roger Gard)

In English, we have a term for that je ne sais quoi: “stuck up.” On this point, my sympathies with Julien run deep.

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero: Brad Hill, of Weblogs, Inc. Some blog! This site, which represents the network of AOL service blogs, has been updated once since Michael Banks’s book was published! I hope that this chapter represents the absolute bottom of the barrel. I wish you could have seen and heard Kathleen when I read aloud to her the “Points to Review.” My favorites:

— Knowing that you have readers can substitute for material rewards.

— Be authentic as a blogger by addressing issues and interests for which you have a genuine passion.

It’s not that either of these propositions is mistaken, but rather the self-help paradox: anyone capable of benefiting from this book already knows these things!