Morning Read

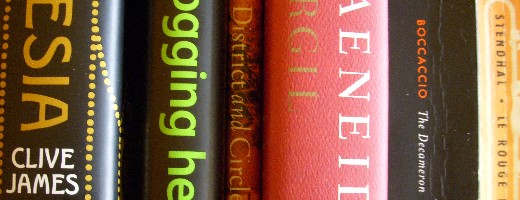

¶ IV, ix of the Decameron is a horror story, plain and simple. Two knights, boon companions, are in love with the same woman — and the one who is married to her descends into homicidal malignancy with what can only be called warp speed, in the space of a paragraph. His former chum rather colorlessly if brutally done away with, we can proceed to the interesting part of the story, which concerns the transformation of the dead man’s heart into a succulent dish fit for an errant lady to feed upon. Boccaccio’s dispatch is — for Boccaccio — absolutely artless, and this tale holds the “slam, bam, thank you, ma’am” honors, at least until something lower comes along. The tale is told, of course, by the dectet’s cutup, naughty Dioneo.

¶ As Aeneas continues through the Underworld, questioning the Fury Tisiphone about the crimes committed by the damned consigned to Tartarus, we reflect on how much sophistication has gone into explaining the afterlife since classical times. Working on the foundations of heroic Mediterranean myths about hell, Christian thinkers thought through every detail of the situation, which was of course not really imaginary to them. Changing everything is the idea that sprouts in Paul and blooms in Augustine: we are all sinners. That is clearly not the case for Virgil; in fact, very few souls are wicked enough to be damned. There is no conception of “venial sin,” and even the mortal offenses are all contingent upon an idea of honor that has nothing to do with the great Christian engine of love.

¶ Seamus Heaney’s District and Circle came out two years ago. It’s your standard slim volume of verse, although one does wonder why such books aren’t formatted for genuine pockets. Eight and a half inches by five and a quarter is absurdly broad. You ought to be able to carry these things around with you, for declamation on the moors.

The title poem’s title alludes to the District and Circle Lines of London’s Underground. On his daily rounds, the poet passes a beggar with a tin whistle — another poet, in other words. It’s for this reason that he keeps his “hot coin” to himself: “For was our traffic not in recognition?” The sonnet is unabashedly well-constructed, as if it were permissible for Heaney to lavish his grand prosodic gifts only upon a correlatively humble scene, one lacking any associations with “poetry.”

I come to this poem with enough knowledge of the world to decipher its not very opaque references, but the poem on the facing page, “Rilke: After the Fire,” is lost on me, perhaps because I don’t know my Rilke.

¶ Clive James knows his Rilke — the nominal subject of today’s essay. The real subject is the fame of those who have been compromised by association with corrupt regimes. Brecht, Richard Strauss, Shostakovich — Rilke himself was gloriously apolitical, and so has nothing to do with this piece, really — the usual suspects. And then an interesting swerve: Charles Lindbergh.

… behind all the personae determined by events there was a personality that remained constant. He valued self-reliance, and possibly valued it too much: it made him hate collectivism so blindly that he thought fascism was the opposite, instead of the same thing in a dark shirt. Yet there is something magnificent about a man who could make a success out of any task he tackled. To complete Rilke’s observation — and it is an observation, because it answers visible facts — we must accept this much: to measure the distortion of life we call fame it is not enough to weight the misunderstandings against the understandings. We have to see through to the actual man, and decide whether, like so many artists, he is mainly what he does, or whether he has an individual and perhaps even inexpressible self, like the lonely flyer.

This is exactly the sort of essay that makes one long to rush off to a café, for group discussion with thoughtful friends. But one is stranded in Yorkville, with only the Internet as one’s lifeline.Â

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero is Brian Lam, of Gizmodo. The interview is so pervaded by references to rivalry with Engadget and the popularity of Lifehacker (a site run by a fair lady) that I very nearly conflated this paragraph with the one about the Decameron. From the bottomless trunk of riches contained in the Points to Review: “Providing up-to-the-minute news can contribute greatly to a blog’s success.” No shit, Sherlock.

¶ It’s Corpus Christi in Le rouge et le noir, and we have a moment that reminds one inescapably of Tosca. As a church swells full of gorgeously arrayed celebrants, our hero swoons to one side, his mind utterly elsewhere. On a woman, of course. Tosca herself in the case of Scarpia, at the end of Act I of the opera; as for Julien, he has just run into Mme de Rênal in a side-aisle. I wonder how many members of Puccini’s early audiences were reminded of Stendhal’s novel, which until only recently it seems was a must-read classic, known to all educated people.