Lost and Found New York

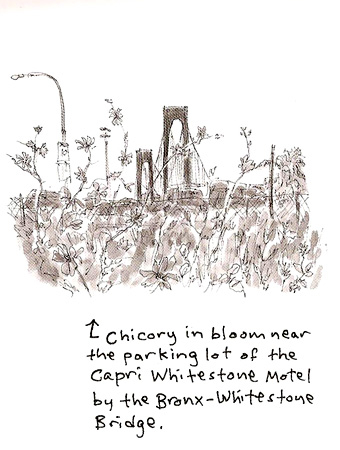

Ever since I began reading The New Yorker, I’ve been a big fan of James Stevenson. His lightly crazed lines have always seemed to conceal secrets: if I looked hard enough, I would understand everything. And, in a sense, I jave I’ve learned that the world is full of unforeseen cracks. That it falls apart, gently, when no one is looking. Even when Mr Stevenson was sketching suburban predicaments for the magazine, his drawings betrayed a fascination with ruin (rephrased as mild dilapidation). More recently, he has contributed a series of full-page narrative illustrations about Old New York to the New York Times. Floyd Bennett Field. The old Hudson River Day Liners. The Gowanus Canal – still with us. Whenever I came across one, I’d clip it and stash it with all the other (unread, stuffed-in-boxes) clippings.

The other day, I sorted through the clippings, throwing away most of them, and wondered, “When is Stevenson going to collect these drawings in a book?” Voilà . No sooner was the question asked than it was answered – even if it took me a day or two to find that out. On the lookout for something different to give to Miss G on her birthday, what do I see in the window of Crawford Doyle Booksellers but Lost and Found New York: Oddballs, Heroes, Heartbreakers, Scoundrels, Thugs, Mayors, and Mysteries, written and illustrated by – James Stevenson. I bought two copies.

It’s a big book, but not a thick one. The illustrations have been spread out a bit, and a number of the larger drawings have been reproduced at something like their original size. The text is every bit as evocative as the artwork. Here’s Mr Stevenson on the house at 933 East 222nd Street, from “Williamsbridge Wonders” (Williamsbridge is a neighborhood in the Bronx):

What 933 is actually made of is almost impossible to detect since most of the house is concealed behind a blaze of churning white wrought-iron. From its driveway gates, featuring white swans kissing floral arrangements, to its remarkable balcony, the house whispers of the tropics.

Makes you want to head uptown and check it out for yourself. Come finer weather…. And yet you’d have to make notes. Carrying the book itself on a tour would be thoroughly inconvenient. Doubtless some genius has managed to download the book onto his (or her!) iPhone.

The structures that Mr Stevenson describes, as well as the institutions that built them and the characters who strutted eccentrically through them (which he also describes), are rarely more than a hundred fifty years old. By European standards, they sprouted only the day before yesterday, and made it through a single night before suffering insidious neglect. Mr Stevenson, however, is able to invest them with all of the romantic charm of Tintern Abbey – with a seasoning of Big Wiseapple acidity. Fittingly, the book opens with a souvenir of the old Penn Station – forever lost, and never to be found.

In her Foreword, Kennedy Fraser captures an idea of the charm of Lost and Found New York:

I have known Stevenson for years, since we were colleagues at the old New Yorker magazine on West 43rd Street. Behind the successful artist and paterfamilias (whose own whiskers have turne dwhite by now) I have often seen what I see in Lost and Found New York, and in the pages of this book: the irrepressible ghost of a slender, boyish Jim, tugging at one’s sleeve. “Hey! I want to show you something really interesting! Take a look at this!”

Lost and Found New York is not the sort of book that hangs around in print for a long time (unless it’s a surprise best-seller, which I rather doubt will be the case here), so take my word for it and get yourself a copy pronto.

Now: what to do with those clippings?