Goldfinch Week:

Ekphrasis

21 October 2013

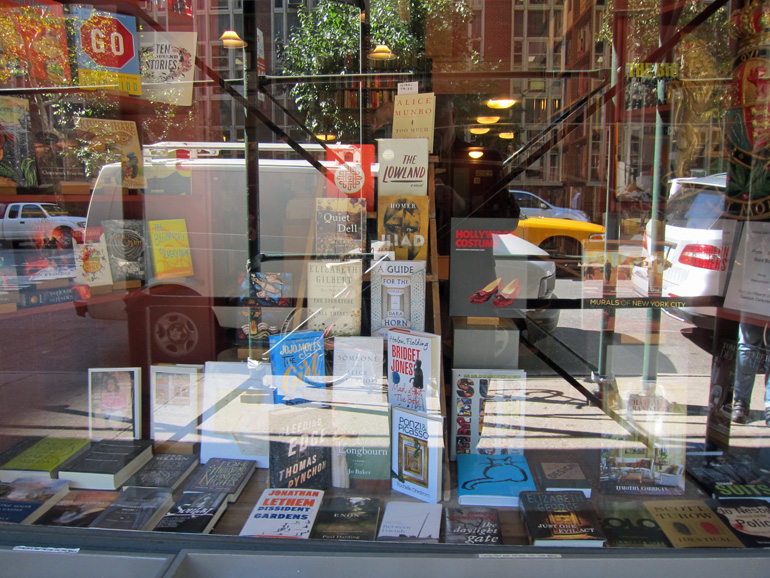

It occurred to me that a photograph of Crawford Doyle’s right-hand shop window, which features new fiction (and poetry), would be a quick way of indicating all the books that I’m not planning to read. True, I’ve read The Circle; and it’s possible that I may relent about Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland, but nothing else in the window interests me. Were I to take a picture tomorrow, the window would include the novel that I read obsessively over the weekend, Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. But I don’t have to go back tomorrow. The good people at Crawford Doyle called me on Friday morning, to tell me that a copy would be mine for the showing-up. I took the picture of the shop window right before pushing into the store and securing my short-term happiness.

I had had the idea for the photograph on Wednesday, when I stopped into the bookshop without any object and wound up buying a book that I already owned. (See the previous entry.) I noticed then that there was nothing in the window that I wanted to read. Once upon a time, I’d have “wanted” to read almost everything, just to keep up. The Lethem definitely, perhaps even the Pynchon. I don’t care much for the prose of either of these writers, and while I found The Fortress of Solitude powerfully stocked with images of Brooklyn, real and imagined, that spontaneously well up on inside me with surprising emotional clout, I came away not wanting to repeat the experience. (With Pynchon, I never had even that much satisfaction.) I would read Elizabeth Gilbert’s historical novel, even though I avoid historical novels. I might even have delved into Longbourn and the new Helen Fielding, just to be in the swim.

(What’s that Alice Munro doing at the top of the stack? I don’t think it was there on Wednesday; and, on Friday, I wasn’t actually looking.)

This illo tempore isn’t so remote, only eight or ten years ago, when I was discovering the joys of the Internet and beginning to write a Web log. It was a sort of high school thing, except that I never went to a high school with a “cool kids’ table.” I never took a seat at the Internet equivalent, either, but even before my disappointment subsided completely, I learned that “keeping up” was not for me. Not if it involved reading highly-buzzed books such as Marisha Pessl’s Special Topics in Calamity Physics, a novel that blathers on for five hundred pages about, well, the cool kids’ table, before finally settling down to a story for a further two hundred. I should never get that far now. There is really far too much great stuff to read for me to find time for every hot new book. To read and to re-read!

On the cover of this week’s Book Review, there’s an illustration pairing Philip Roth with Norman Mailer. Yikes! To me, these writers are grand pianos that fell from high windows moments after I stepped over their impending crash sites. What if I had devoted significant time to reading and thinking about them, just because so many people who write about books found them important? (Mailer is already palpably not important, but that is something that I have lived long to see.) I learned early on that writing about books that were important to other people, but not to me, would be a terrible waste of time, because it would distract me from the vital business of trying to explain why the books that are important to me are.

And why is that important? Who cares what I think? Well, if thinking came into it, I could see the objection. But what I want to do, when I write about books here, is to show something of what it looks and feels like when a good book touches a mind. Matthew Arnold wouldn’t have put it thus, but this, I think, is what he was calling for, in Culture and Anarchy, still the most important book that I’ve encountered on the subject of the best things in life. Every good book deserves a bouquet of such reports. Someday, I hope, publishers will learn to collect them.

***

The first thing I did when I finished reading The Goldfinch was to see what James Wood had to say about it. His review appeared in last week’s New Yorker, which was irritating in itself, since what is the point of reviewing books that readers can’t go out and buy that instant? Why tease people? This irritation was was somewhat specious in my case, as I wouldn’t have read the review until I’d read the novel. Wood is a writer of great substance, and I wanted to read Tartt’s new book without being under any thoughtful person’s influence.

As The Goldfinch came to an end, I had a feeling that Wood’s judgment was going to be net unfavorable, and I was right.

The bounty, literal and figurative, at the center of all the absurd legerdemain of The Goldfinch is the painting of the same name by Carel Fabritius, a student of Rembrandt. It is a serene study of habituated imprisonment: a finch, one of its feet attached by a ring and a short chain to the little box it is perched on. This gemlike masterwork powers Tartt’s narrative: it is seen and cherished at the Metropolitan Museum by a boy and his mother, stolen by the boy, hidden, stolen again by someone else, and finally recovered. It occasions some of the deeper writing in the book, as Tartt slows from her adventurous storytelling to the eventless calm of ekphrasis, and describes the mournful splendor of Fabritius’s own painterly patience. But, alas, it is surrounded by prolix scrawls of novelistic impatience, and eventually the noisy tension between the two works, Fabritius’s and Tartt’s, becomes acute. The Goldfinch (1654) and The Goldfinch (2013) are birds of a very different feather. Tartt’s consoling message, blared in the book’s final pages, is that what will survive of us is great art, but this seems an anxious compensation, as if Tartt were unconsciously acknowledging that the 2013 Goldfinch may not survive the way the 1654 Goldfinch has.

This is a potent dismissal, and Wood spends the remainder of the review supporting its crux by pointing to various instances of “prolix scrawls of novelistic impatience.” If, in the end, I disagree with Wood, I still don’t think he’s wrong, because the familiar (Wood would say “clichéd”) tone of Tartt’s “adventurous” narrative clearly lacks the lapidary sparkle of James or Nabokov, two writers whom Tartt professes to admire, and if a reader, any reader, Wood or you or me, feels this absence of stylistic verve to be a failing, then that is that. And Tartt herself, through her narrator, tells us why.

A great sorrow, and one that I am only beginning to understand: we don’t get to choose our own hearts. We can’t make ourselves what’s good for us or what’s good for other people. We don’t get to choose the people we are.

“Only beginning to understand”: the narrator is all of twenty-seven, and if this insight were phrased any more artfully, it would be hard to swallow, because the awful truth about the ineffability of our hearts does not dawn on most people, even the most thoughtful, until they’re closer to the author’s age. (Donna Tartt will be fifty by the end of the year.) I swallowed it without a second thought, however, because, whether from want of refinement or some more positive characteristic, I never felt a “noisy tension” between the painting and the novel. I felt that they went together very well, almost perfectly. “Ekphrasis,” indeed. The illumination of one kind of art by another necessarily works both ways: the source of inspiration explains the illumination.

I do need to catch my breath, though. I did nothing yesterday but fix a little breakfast and read The Goldfinch; I never even looked at the Times. So, mindful that the book is still not generally available, I’ll deliver my book report in installments.