Gotham Diary:

Exhaustion from Diligent Service

The weather was awful — snow! — but I had to get out of the house. I had to get a haircut, but that’s not what I mean; I had to break out of the ordinary routines, which regular readers will know about my fiddling with since the New Year. The new ordinary routines are working well; they’re much more flexible thant the old ordinary routines. But they’re also much more conservative: the list of things to do is quite a bit smaller. In fact, it’s comprised of necessities. There has been no room in the routines for optional entertainments. That’s why, although I’ve been writing well and regularly, I’ve been circling my navel so far as subject-matter goes. I had to get out of the house in order to have something fresh to report.Â

How conservative? My idea of “something fresh” was a trip to the Museum. Oh, boy; how exotic! Sad truth is: it has gotten to be exotic. I’ve been to the Museum once this year, and that was to take my grandson on his first visit — to get him out of the house on a cold day. He and I did not study the curios, exactly; from my point of view, the trip was all about him, not the Museum.Â

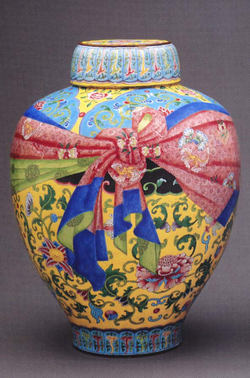

Today, I vowed, I would go to the Museum and see something new. The Qianlong Emperor obliged. More about him in a minute. Even better, the Museum’s curators obliged. I saw something old — old and very familiar. In a show complementing the exhibition of knickknacks from the emperor’s retirement pavilion, constructed in the Forbidden City in the 1770s, the Museum has displayed one of the few treasures that I long to possess — a large painted-enamel ginger jar. The Museum has two of them; I’d be happy to let it keep one. (As long as they’ve got the pair, though, I wish that they’d turn one of them around, so that I could inspect the back.)Â

What I love about the jar, aside from its riotous tackiness, is its cosmopolitan flavor; in a vitrine with other Chinese decorative objects, it stands out as foreign. And it is foreign. According to the label, one of the patterns beneath the illusory wrapping looks more Indian than Chinese. The technique of painted enamel was developed a few centuries earlier in Limoges. The Chinese, after all, didn’t invent everything. The Qianlong period (1736-1795) was unusually open to foreign styles; the Jesuits were still providing the emperor with a window on the West through which European styles were allowed to pass. One of the objects on display this afternoon — I don’t think that it came from the Forbidden City — was a perfectly frightful vase with long panels showing ladies in French court attire romping beneath parasols; the panels are “framed” with half-carat crystals. Unlike my ginger jar, it’s heavy and dreary and an embarrassment really.Â

The conceit of the ginger jar lies in the incompatibility of the patterns above and below the trompe-l’oeil cloth wrapping; it’s as if the broken top and bottom of completely different jars had been glued together, with the swath of ribbony fabric concealing the join. You don’t notice this right away, though, because the cloth itself is so busy: layered fantastically in three colors, embroidered with a tiny pattern, and overlaid with floral emblems that don’t quite tuck into the folds. The whole thing comes this close to being one of those horrors that you used to see in the furniture showrooms on Grand street — when Grand Street was still part of Little Italy. With a ghastly tasseled lampshade.Â

I can’t help thinking of the Qianlong Emperor as the Chinese Louis XV. Their long reigns overlapped considerably, and were characterized by an easygoing opulence and a nonchalant grandeur that inspired the production of a lot of beautiful things. (And their régimes were equally doomed, even if it took China more than a century longer to tumble into the abyss.) Of course we know a lot more about the French king than we ever will about the Chinese emperor; it’s not difficult to bring the lazy and sensual but warm-hearted and good-natured Louis to life, but the personal qualities of the Qianlong Emperor are so much rubble beneath the official transcripts of his reign, in which almost everything occurs as it was supposed to occur. (There are no reliable unofficial transcripts.) Poor Lord Macartney never got to have the tête-à -tête that would have allowed him to take the emperor’s measure; the wall of officialdom that blandly blanketed the empror was never breached.Â

A nearby vitrine held an assortment of medium-sized lacquer dishes and boxes. I wondered, as always, what they are like to hold. The thought of what it must be like to have to keep a piece of lacquerware dusted led immediately to the guilty recollection that I’ve forgotten all about my resolution to re-read The Dream of the Red Chamber, also known as The Story of the Stone, all four Penguin volumes of which rest beneath my bedside table. I have Volume I in my hands as I write. A Taoist is talking to a large, inscribed stone — a stone that has everything written on it save the authentication of a dynastic date. Somehow, the stone is going to be sent down to participate in the great illusion of human life — it’s probably best not to dwell on the mechanics. When does the story get going? If I could only get past this prefatory mumbo-jumbo….

I have been thinking lately that I ought to stop reading new books for a year and just re-read old favorites. The Tale of Genji. Austen, Eliot, and James. And Forster. And Waugh. The barber today asked me to recommend a book. He’s from Peru and he wants to improve his English by reading a book that is interesting but not too difficult. I almost suggested Vile Bodies. The language itself is not very difficult, as I recall. But the goings-onmight shock him, might sail right over his uncomprehending head. I recommended Sarah Bakewell’s How To Live, the book about Montaigne. Tito may never ask me to recommend another book, but it will be for a perfectly respectable reason.Â

Ah, there’s nothing new here at all! It looks like I’ve fallen back on my old game, trying to write about the same old things with a hint of freshness. How well I’d have fit in at the Qianlong Emperor’s retirement pavilion,which was called, by the way, the Juanqinzhai — the Studio of Exhaustion from Diligent Service.