Reading Note:

Theroux on Gorey

Alexander Theroux’s The Strange Case of Edward Gorey is a strange case in its own right. An unbroken essay of 166 pages, including occasional and often miscellaneous illustrations, this series of sketches of a famous friend rambles senescently across a small patch of ground. You sense that the mere organization of the material into discrete chapters would show up enough repetition to warrant cutting the text by about a third, but this is not to complain. If you find that this little book is making you impatient, put it down and save it for a more congenial time.Â

Nothing could be more fatuous than recommending or otherwise evaluating the Strange Case. If you’ve ever fallen beneath the spell of Edward Gorey’s work, you’ll want to read it. When you discover that it is neither an objective biography of Gorey nor a measured consideration of his work, but instead a rather doddering memoir that tells you at least as much about Theroux as about his subject, you will feel at least a moment of keen disappointment; whereafter you may either throw the book against the wall or continue reading with adjusted expectations. In the latter alternative, you will not object when Theroux goes on about Sainte-Beuve, Beardsley, Auden, or other to him kindred spirits. You will not try too hard to grasp the point of mystifying anecdotes. You will probably not even wonder why Fantagraphics Books, which published the Strange Case in 2000, in paper, declined to “do anything about it” when issuing a hardcover edition just this past January. (The Strange Case of Edward Gorey is much too strange to be fixed.) Above all, you will not mind that Gorey never sticks around long enough for you to get a good look at him. You wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Theroux wrote this book, which at first you might have thought Gorey would hate had he lived to see it, to hide his friend behind a smokescreen of plausible chit-chat. Consider:Â

I attended a party at my brother Paul’s house in 1983, just after Lady Diana’s wedding, when Gorey’s highly amusic if satirical comments on the overluschness of the Princess’s wedding gown (delicious acres of crushed ivorty silk-taffeta and lace embroidered with mother-of-pearl sequence of pearls [sic], something she herself very soon thereafter came to agree with, at first scandalized Tina Brown and Harold Evans who were also guests, having just more or less arrived at the time to take their respective positions with anity Fair and New York Times [sic] but who had clearly never quite met anybody like Edward Gorey with his wistful, somewhat dramatic manner, filled with hyperbole and curmudgeonly wit. My understanding was that they did not initially like him. They had never seen such a person. To their credit, they caught on quickly to the slant of his humor and soon everything went swimmingly. I can still see him in my mind’s-eye walking to his car in the rain under a big cherry-handled cotton umbrella.Â

What can one ultimately say in defense of a person who with studied conviction quite unequivocally preferred the company of cats over human company?…

This is enormously unkempt; if I were glancing through a blog entry written with such carelessness, I’d give its site a pass. Everything potentially interesting about the passage is buried, as if in a black hole, in the sentence that begins by giving the Evans-Browns credit for “catching on.” Theroux might have done a better job of putting us in the picture by reminding us that the oddness of Gorey’s appearance would have been intensified by his being dressed like an overgrown high school student, inappropriately attired for the task at hand, and by his sporting hefty iron rings on all of his fingers. But we would still be left with an odd dissonance: although it was clearly desirable from Theroux’s point of view that Gorey get on “swimmingly” with the English newcomers, it’s highly unlikely that Gorey gave a damn what they thought about him — a conclusion that’s clinched by the strange final sentence, which has nothing to do with anything: exactly! The first sentence of the following paragraph carries us even farther away from Gorey, whose lack of interest in the opinions of others might seem autistic were it not more likely that he had good reason to rely on his eccentric manner to rally a contingent of supporters. He would not have cared what Theroux said in defense of his preference for the company of cats. I can almost see him patting Theroux gentle and suggesting that, “ultimately, you can say that I died on the last page.”Â

I can see that gesture because Theroux does a pretty good job, if only by aggregating instances, of conveying a sense of Gorey’s performance mode. If you have lived among creative types in a big city, Gorey’s behavior will not be so terribly unfamiliar; it follows one of several available standards of “impossibility.” Witty, capricious, and determined to mix things up, Gorey seems to have been one of those smarty pants whose opinions about almost everything are formed as if in a vacuum. You could not infer from his fondness for Buffy the Vampire Slayer that he would look down his nose on Cavalleria rusticana. For the matter of that, his disdain for the opera might be temporary, the whim of a mood swing — don’t hold him too it! (Gorey took the kind of interest in silent films and in the actors who appeared in them that would eventually make Botticelli a much-loathed game.) Theroux insists upon his generosity, and I don’t doubt that he was free with his professional services, as well as in other material ways. But he was not intellectually generous. It may have had something to do with his being, as he put it, “undersexed.”Â

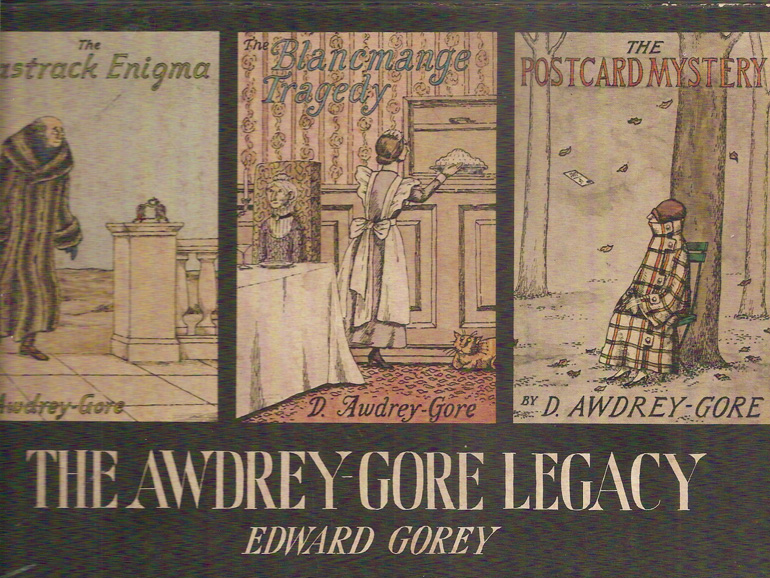

What made Edward Gorey stand out, as the Strange Casehammers home with nails of negative implication, is the work, the work that Gorey hated to discuss. I can’t exaggerate my admiration for this disposition; it seals my faith in Gorey as an artist. His work was complete; there was nothing left over to talk about. If there remains plenty to deconstruct, if Gorey’s work seems to beg for unpacking, it is nevertheless clear that it can’t be decoded — all the signs are overdetermined, and then compressed in the clichés and references of a narrow swathe of popular culture. Assuming that one of his dark little stories “means” anything, it would mean a great deal more than the materials out of which it was made. To say that a certain drawing is reminiscent of the style of a frame from a Charlie Chan movie (not a comparison made by Theroux) would serve only to make the movie seem paltry. Gorey brought two special ingredients to his mash-ups, a highly-wrought and perfectly consistent decorative style and an irreppressible sense of humor that was perfectly coordinated to his sense of design. Theroux tells us that Gorey spoke in giggles. Without making a sound, we giggle at his squiggles.Â

I came away from The Strange Case of Edward Goreyrather relieved that I never met the man in passing. But IÂ surmised that he would have made an interesting neighbor. At his memorial service, we’re told, a number of people who were not mutually acquainted claimed to have been Gorey’s best friend. As for his dislikes, you have to imagine that he would never have spilled them onto the pages of a book with the gusto displayed by Theroux. Martha Stewart, Barbra Streisand, Barbara Walters, and Oprah Winfrey all get withering goings-over by Theroux’s basilisk prose, as do popular genre eminences such as Stephen King and Dean Koontz. The word “vitriol” comes all too often to mind.Â

His standoffishness vividly came through in an appearance he made in 1997 on the Dick Cavett Show, which was pretty much of a disaster. With his characteristically pretentious and intrusive self-importance — those phony Yale witticisms — Cavett, right in his element, was clearly trying to score off his unassuming and visibly uneasy guest from the very first moment with the farcical banter he presumptuously assumed an original, thoughtful man like Gorey would expect. Gorey, out of shock, I suspect, but maybe disgust, was virtually mute. He gave one-word answers, nettled replies. A public forum was not anything he enjoyed. Quipping with fools or professional girdle-salesmen was certainly not what he was about. “I see,” he invariably said softly as the dry, gloomy response to anyone feeding him a line or trying to cozen him. “I was under the impression that this was leading somewhere.”

There’s a lot of dish in Strange Case, from the mention of which I could easily transition into the complexities of its grapplings with sexuality — but I won’t. It’s enough to mention that the most annoying thing about this book is its heterosexual author’s overdeployment of the epithet, “a gay thing.” Given the facts, it’s unclear what this really means, since Gorey appears to have coupled an array of campy behaviors with genuine celibacy: he really did prefer the company of cats, and might very well have been a hermit if he hadn’t liked to talk so much. Theroux may be using “a gay thing” to draw Gorey into a community (even if it’s one that Theroux himself doesn’t belong to), but the effect is invariably diminishing and even borderline homophobic. Nobody on earth for whom the observation might otherwise be interesting needs to be told that a taste for mauve is “a gay thing.”Â

Gorey fans will be familiar with The Listing Attic, an early collection of really rather good limericks, two of them in French and one quite magnificently getting revenge on “some Harvard men, stalwart and hairy.” What I did not know is that Gorey may have picked up this knack from Auden, whom he hugely admired. I think it best to conclude this page in Theroux’s entertaining spirit at its best, with a truly impressive poem by Auden that sports, among other things, no end of internal rhymes.Â

The Bishop elect of Hong Kong

Had a dong that was twelves inches long.

He thought the spectators

Were admiring his gaiters

When he went to the gents’. He was wrong.