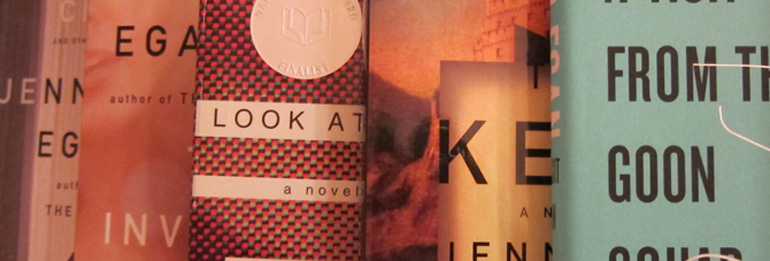

Reading Jennifer Egan (et alia):

Intense and Enigmatic Joy

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

Among the writers presentging their foundation  mythologies — how they became readers and writers — in the Summer Fiction issue of The New Yorker is Jennifer Egan. Egan offers up her brief career in “Archeology“; having realized that she was too squeamish for the pulse and flow of medicine, she was attracted by the dead humans of paleontology. Visions of foreign travel and exotic climes were splintered by the blinding heat of a field in Illinois. Her experience with a square meter of Native American remains started badly but improved, and when it improved to the point where Egan had learned what she needed to learn from it, she went back to San Francisco and saved up for a sojourn of non-invasive contact with living Europeans. “But my sojourn in Kampsville has stayed with me—the sensation I had of scraping away the layers between myself and a lost world, in search of its occupants.”

And I thought, is that it? I am still trying to put my hands on the qualities that make Egan’s fiction special. The best that I can do is to say that she captures in her prose — which is to say that she does more than merely describe — the temptations of the glamorously dodgy. Her characters are almost always doing something wrong, but it is rarely something very wrong: a matter of misdemeanors, not felonies. In A Visit from the Good Squad, Sasha not only steals things — little things, like cheap binoculars and pens and a child’s scarf — but she sets them out, as trophies, in her flat. Somehow the display seems as wrong as the kleptomania, and possibly worse. But it’s easy to miss what Egan’s characters avoid (for the simple reason that Egan is a mistress at leading the dance of fiction): the vicious and the disgusting. Their sins are sins of weakness, of giving in to the glittering trinket. And yet Egan invests these sins with all the desperate loss of Eve’s biting into the Apple, and then offering it to Adam. The first sin didn’t much look like one.

If it takes me a while to figure Egan out, I won’t mind. I’ve known her work for little more than a year (in which I’ve read everything, some of it twice), and that’s not very long for taking the measure of subtlety. It occurs to me that Egan belongs to the small company of great women writers because, unlike notable male novelists, she doesn’t trumpet her emotions or swish her toe in the nostalgia of lost youth; while, unlike the run of women writers, she takes an ironic (displaced) view not only of her characters but of the very art of fiction as well. (I maintain that the PowerPoint chapter of Goon Squad is a triumph of imaginative literature, and perhaps the degree zero of graphic fiction.) And while Egan assuredly wants to be read, I doubt that she wants to be grasped. (Men always do, and complain that they never are — why is that?) Much as I’d like to roll out a critical reading of Jennifer Egan that sparkles with insight, I’m going to distinguish between wanting to do it and wanting to have done it. I’m not going to let the latter impulse (which is of course the stronger) hurry me.

What a prolix old fool I am: this was meant to be an apology for not having finished John Armstrong’s In Search of Civilization, a book that makes a number of highly sympathetic arguments about the linkage between virtue and prosperity (linkages, I say, not causalities). I completely share his horror of populism and its works; I also share his interest in popularization, which is the art of taking the trouble to strip away the non-essential accretions of sophistication from things that are beautiful and true. At one point, in connection with Abbé Suger of all people, Armstrong insists on the importance of charm. Can you think of a quality more deplored by modernism? Today’s cognitive revolution is demonstrating the many ways in which warmth and sympathy are vital to human fulfillment, and how deeply even the chilliest of us crave them, but our artists are taking their time about getting the message.

Realizing that I wasn’t going to be able to say anything solid about Armstrong’s book, I broke off at a keenly interesting place and went downstairs to collect the mail. Along the way, I read another foundation story, Salvatore Scibona’s “Where I learned to read.” The question has two answers. The first really answers a slightly different question: Where I learned that I wanted to learn how to read. That took place in an old shack outside his working-class home. The answer to the title question is “St John’s College at Taos.” Regular readers will know that nothing makes me happier than hearing about young people buckling down with the great books and loving it. “All things considered, every year since has been a more intense and enigmatic joy.” Exactly.Â