Gotham Diary:

Properly and Naturally Amassed

April 2018 (IV)

Tuesday, April 24th, 2018

24, 25 and 27 April

Tuesday 24th

David, of course, was used to his mother’s busy people-filled life. As she liked to say, he had been brought up “on coats,” meaning she had dragged him along to the many parties and “happenings” and other events she had not wanted to miss just because she had a young child. … In fact, though he had a much stronger sense of privacy than Susan did, like her, he grew bored and restless when things were too quiet. He also had her stamina, and though he was perhaps somewhat less social than she, he was far more social than I, who already carried the seeds of the person I would become: someone who spends ninety percent of her time alone. (76)

That’s Sigrid Nunez, in Sempre Susan: A memoir of Susan Sontag. I read the book yesterday, with the greatest pleasure. I had understood it to be something of a hatchet job, but it wasn’t anything of the sort. Although Nunez itemizes Sontag’s foibles, she does not ridicule Sontag herself. She presents her rather as a mixed-up person like all of us, only much more determined to be famous. This pursuit of fame, which used to be positively admired in men, is treated by Nunez with kindness and generosity. She finds two great flaws in Sontag’s professional character. In the only passage in the memoir that I found “judgmental,” Nunez deems her subject to have been “mortally malcontented,” largely because, although famous, she wasn’t famous for her fiction. The other flaw, seemingly fatal for a writer, was that Sontag hated being alone. She had two ways of dealing with this problem, according to Nunez. She would create the undergraduate fugue state of dexedrine-fueled all-nighters, obsessively combing through piles of books in search of the mot justissime, or she would rope in a friend to play editor, and the two of them would decide where the commas belonged.

Meanwhile, Nunez was carrying those seeds.

***

I put the book down and talked about it with Kathleen — without whom I should certainly be someone who lived alone in more ways than one. I observed that I have never learned much from people directly, except, and I’ll come back to this, about who they are. What I mean here is that I’ve never learned how to live from the example of another person. I have never had a role model or a mentor. I thought for a long time that this signified a moral failing of some kind. Instead, I learn from books. And I learn, or demonstrate what I have learned, by writing. Reading and writing are something of a mining operation in which I excavate and assay myself and so find my place in the civilization around me. It is not an image that I want to push very far, but it feels like an apt description of how I have spent my life most profitably. The restless socializing, occasional thrill-seeking, the longing to find myself embedded in the alienated but romantic scenario of an Antonioni film — these were enormous, sometimes nearly catastrophic wastes of time, at least to the extent that it took so long to figure this out. The wonderful thing about being old is having outgrown, outlived all such urges.

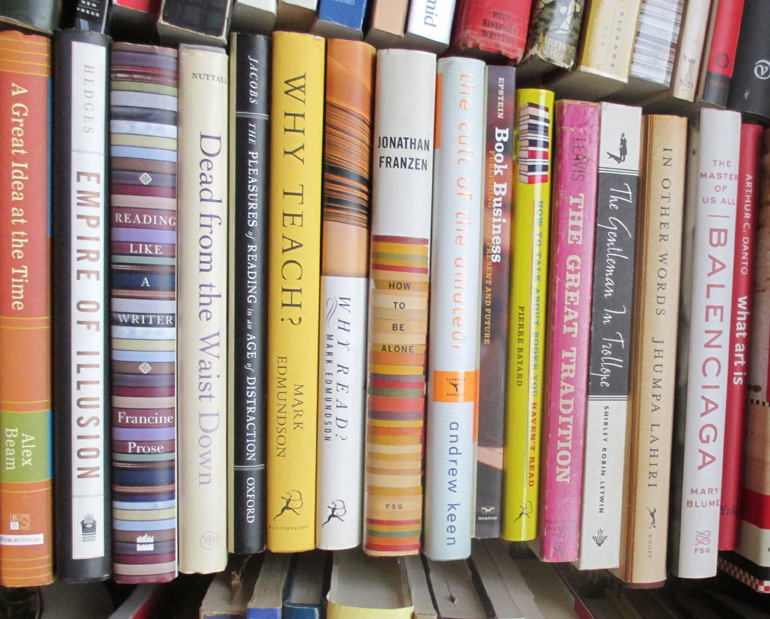

What could be less “popular,” less “American,” less generally recommended, though, than learning about life, not from people directly, but from books. An interesting point occurs to me. Looking for wisdom in people, I would focus on one person at a time, as if interviewing prospective gurus. Nothing extraordinary about that. But with books, I was never looking for right one, the book that would unlock the secrets of the universe. (I’m amazed by the number of books that make such claims.) Certainly there were books that made an extraordinary impression at the time, but they never prevented me from reading other books, books that I never expected to be revelatory. When I say that I learned from books, I mean exactly that: from an undifferentiated pile, variously digested, of texts. It was only when I had read thousands of books — I hope that nobody takes that for a boast; it would be lame of me indeed if I could not at least make that claim — that the learning began, that the writing took on a purpose.

Kathleen — remember that we have spent more than half our lives together — agreed.

***

What I have learned from people is about them. This may have been what slowed me down in school: I learned more about teachers themselves than about what they were teaching. I’m not talking about secrets here. I learned what made people smile, what their smiles were like, what made them cross or impatient; I learned whether they were generous or mean (although almost everybody is both). I learned most about people when they were not paying attention to me — although this was another thing that it took me too long to realize. I would have learned more if I hadn’t been so fond of talking. I still like to talk, and Kathleen, bless her, insists that she likes to listen. But, more than ever, I like to watch people.

At lunch in a quiet restaurant, I am annoyed when my reading is interrupted by a telephone conversation that I cannot help overhearing half of. Sometimes, in cases of great witlessness, both halves — is there anything as passively obnoxious as activating the speakerphone option in a public place? These intrusions are never quite entertaining enough to justify the nuisance, probably because people who conduct private business in the company of strangers lack rudimentary discernment. Actual conversations between people sharing a table can be just as bothersome. The other day, I could not shut out the Elmer-Fuddish monotone of a sensible, plain-speaking Midwesterner as he lectured a younger person, who might have been his daughter but who was probably, given her animation, a more distant relative, on the virtues of an IRA account. Everything that I heard come out of the man’s mouth was worthy of the very earliest pages in some Life for Dummies handbook. No sooner had the two of them left than a woman about my age took a seat. She was not very glamorous to look at, but her voice reminded me very much of Diane Keaton, Diane Keaton at the beginning of Something’s Gotta Give, when she can’t wait to get rid of Jack Nicholson, her very laugh a sigh of dismissal. I couldn’t help feeling a little sorry for the waitperson, with whom this customer was going to be both chummy and demanding. Not long after she had ordered, her phone rang — the “old phone” ringtone. All I could make out was that she was looking for a better package than what they were offering. If you’re going to complain like Diane Keaton, perhaps you had better look as good as she does, too.

***

Wednesday 25th

The last page of Gitta Sereny’s Into That Darkness, a meditation on responsibility, built on interviews with Franz Stangl, the Kommandant of the Treblinka death camp, is entitled “Epilogue.” But it is actually a closing prayer. Here are the first and the last two paragraphs:

I do not believe that all men are equal, for what we are above all other things, is individual and different. But individuality and difference are not only due to the talents we happen to be born with. They depend as much on the extent to which we are allowed to expand in freedom.

Social morality is contingent upon the individual’s capacity to make responsible decisions, to make the fundamental choice between right and wrong; this capacity derives from this mysterious core – very essence of the human person.

This essence, however, cannot come into being or exist in vacuum. It is deeply vulnerable and profoundly dependent on a climate of life; on freedom in the deepest sense: not license, but freedom to grow: within family, within community, within nations, and within human society as a whole. The fact of its existence therefore – the very fact of our existence as valid individuals – is evidence of our interdependence and overall responsibility for each other.

There are no names on this page, no specifics — as befits a common prayer. Nevertheless, I take it to mean, in particular, that, had he grown up in a better world, without an abusive parent and then the social collapse into fascism, Franz Stangl would have remained a working man, as he was before and after his Nazi career as the attendant to exterminators. I don’t take it to mean that Stangl, in particular, wasn’t fully responsible for what he did, but only that we are none of us fully responsible for ourselves, and that we are all somewhat responsible for one another. Human society depends on this interdependence, but as we have seen again and again it is prone to break down when the reach of that society stretches too far, too quickly, beyond conceptions of family, community, and nation. At this very moment, thousands of American men — I hope they are only thousands — are nourishing the worst in one another, forming an adamantine opposition to the intrusion of “human society” into American life.

As it happens, I am also reading some of the essays in Lionel Trilling’s collection, The Liberal Imagination. Sadly, none of the essays bears this title, or describes what it refers to, but the opening essay, “Reality in America,” makes it clear to me that the book’s title ought to have substituted “American” for “liberal.” Writing during the Forties, Trilling could assume that ours was a liberal society, at least for the moment. He could write, in the Preface, that “nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation.” Not that he was complacent: he could project from recent European experience the lesson that “it is just when a movement despairs of having ideas that it turns to force, which it masks in ideology.” Even without the menace of a conservative movement (one that, at that very moment, ironically, was furiously developing ideas, mainly in the brain of William Buckley), there was for Trilling the crack in the liberal, or American, outlook:

Its characteristic paradox appears again, and in another form, for in the very interests of its great primal act of imagination by which it establishes its essence and existence — in the interests, that is, of its vision of a general enlargement and freedom and rational direction of human life —it drifts toward a denial of the emotions and the imagination.

Trilling gives this thought an almost poetic expression in “Reality in America.”

We live, understandably enough, with the sense of urgency: our clock, like Baudelaire’s, has had the hands removed and bears the legend, “It is later than you think.” But with us it is always a little too late for understanding, never too late for righteous, bewildered wrath; always too late for thought, never too late for naïve moralizing. We seem to like to condemn our finest but not our worst qualities by pitting them against the exigency of time. (18)

So much has changed since Trilling wrote — which is practically the same thing as to say, during my lifetime — but not that. If anything, the tendencies outlined in that passage have, if you’ll allow me, massified, grown like the biceps of a committed weightlifter. They have done so primarily by means of broadcast television and its spawn: the biggest mistake that any media critic could make would be to downplay in the slightest degree the fact that our entertainments are mirrors distorted to flatter us. Understanding and thought are not only dull but idiosyncratic: it’s hard to understand what someone else is thinking, no matter how lucidly the thought is presented. But wrath is exciting, and what better way to wind up a sitcom episode than with a bit of moralizing? Bad enough for shows, these tendencies have wrecked the very idea of “news,” occluding complication with violence of every kind, from the automotive to the meteorological, and reducing public figures to the vocabulary of pap.

The liberal vision of enlargement and freedom and rationality — I would put it, the enlargement of civil freedom — is, like all hope, somewhat opportunist, ready to extrapolate success from promising signs, to expect that rackety improvisations will stabilize in time, and, ultimately, to invite disappointment. When we consider what happened in and to the United States during the forty years after Trilling’s preface, by which time only dimwits admitted to being liberal, the Columbia professor’s prescience can seem otherworldly. But I think that Trilling was simply more aware than most Americans wanted to be of the difficulty of the liberal project, and of its dependence for success upon a rigorous, not a freewheeling, imagination. The climate of life in which a human society can flourish on Earth demands much more than heartfelt commitment. That’s where things begin. From there, it is a matter of long, hard thought.

***

Friday 27th

If I have ever read everything in Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination, then I have certainly forgotten it or, more likely, grown a different mind. In the past couple of days, two passages from essays in the the later pages of the collection have shocked me.

[T]here can be no doubt that a society in which homosexuality was dominant or even accepted would be different in nature and quality from one in which it was censured.

**

A prose which approaches poetry has no doubt its own values, but it cannot serve to repair the loss of a straightforward prose, rapid, masculine, and committed to events, making its effects not by the single word or by the phrase but by words properly and naturally massed.

The first comes from “The Kinsey Report” (p 241) and the second from “Art and Fortune” (p 273) Both are offensive in more ways than one. The functional equation of homosexual dominance and heterosexual acceptance is as bizarre, or gratuitous, as it is grating; the implication that the nature and quality of a society in which homosexuality is censured are superior to those of the hypothetical alternative is, among other things, evasive. This is clearly a topic about which Trilling believes that the less said is the better. He has postponed this distasteful discussion of “sexual aberrancy” almost to the essay’s final paragraphs. The other passage, which is preceded by comments on T S Eliot’s judgement of Nightwood, a novel whose name Trilling does not disclose, even though he must assume it to be common knowledge among his readers — more distaste; if you look up Djuna Barnes today, Google will tell you that Nightwood is “a classic of lesbian fiction” — yokes poetry to femininity and prose to masculinity, with the latter alone capable of “words properly and naturally massed.”

These remarks are offensive — today. Trilling, writing in the Forties, seems unaware of making controversial or exceptionable statements. His opinions are delivered with a conviction that can afford to be understated. And I do not think that he was mistaken. These are not the only instances of Trilling’s expressed belief in the salubrious superiority of maleness. (“Masculinity” is the figleaf essential to decorous writing.) It was widely if not universally shared at the time; alternative beliefs would have raised eyebrows. And yet they betray a certain unease, the “concern” that might attend efforts to extinguish a fire before it gets out of control. Kinsey and Eliot, perhaps without realizing it, are encouraging the forces of anarchy and upset. To be sure, Trilling is far more worried about the deadly substitution of ideology for ideas in American discourse, and with good reason. Very much contributing to the shocking effect of the passages that I have copied out is a tone quite unlike that of most of the text. As I say, it would seem that if Trilling could have figured out a way not to mention homosexuality at all in his critique of the Kinsey report, he would have taken it, and the entire collection is shot through with admiration for Henry James, whose sexuality was, in those days, a secret almost brutally suppressed by Leon Edel’s control over access to Harvard’s Houghton Library.

And yet I cannot help but be upset by these glancing blows. They betray the power of common, deep-rooted prejudices in a very fine mind.

Bon week-end à tous!