Boys don’t need much of an excuse to get on well together, if they get on at all.

William Maxwell drops this observation into the third chapter of his final novel, So Long, See You Tomorrow. When I read it for the first time, just last week, this was where I took a break, so that it was the last thing I read and then the first. What does it mean? Or, rather, how did it fit my own life? It wasn’t that I didn’t get on at all. But I did seem to need some sort of excuse to carry things further, to the point of getting on well — friendship. My lack of friends was, of course, thought to be a bad thing by everyone. One must have friends! But I needed something else more than I needed friends, or, rather, something that I had to have before I could have friends. I could never have said, at the time, what this was. Now I can, and quite easily. What I needed before I could have friends was adulthood, or at any rate my own version of it. I needed my way of thinking, my familiarity with history and the arts. I needed to know where we all were. Once I had that, I was ready to make friends with anyone who saw things from a similar perspective.

What I’ve just written is the result of a week’s puzzling. A week of noticing Maxwell’s observation as it flitted in and out of consciousness. A few other things came to mind as well, including two childhood connections that might or might not merit the name of friendship. One of them lasted a lot longer than the other, which I doubt lasted a year. They overlapped in 1958 or 1959, when my family lived on Hathaway Road in Bronxville PO, technically Eastchester.

***

Tony Frascati was the older son, and oldest child, of Dr Frascati, a short, round, gentle but frequently exasperated Italian-American. The exasperation was often caused by Tony, who, unlike his little brother and sister, took after his mother: he was tall and trim and brilliantly handsome. Mrs Frascati was just plain Italian, but that was the only plain thing about her. She was a war bride. I’m quite sure that, in Italian terms, she was a perfectly respectable girl. But she was also a beautiful woman. I see that now. At the time, she was the weirdest human being I had ever met. Aside from a very dreary string of Russian building superintendants and dour German cleaning ladies, she was my first European, and she was vibrantly alive to a degree that my mother, and ladies like her, would never have permitted.

She thought I was pretty weird, too, I think. I remember her looking at me with a kindly squint. I liked to read too much. Well, everyone said that, but, coming from her, it was more of a question. She was the only person who seemed potentially interested in finding out why I read so much. (In my experience, the answer to this question, where children under the age of ten or eleven are concerned, is always the same: escape. My years of reading for pleasure lay in the future.) For a big boy, I sat too quietly and tried too hard to be polite — unlike Tony, who was a noisy shining prince. Efforts at politeness were most severely taxed whenever my visits intersected with mealtime. It would be years before olive oil and garlic and artichokes and salamis that would never be found at Gristede’s would cease to be as exotically unappetizing as, say, popping a writhing little octopus into my mouth. Mrs Frascati, wearing something between a housecoat and a peignoir, her blondish hair pinned up in an improvisation, would walk around the table, putting dishes in front of us while we sat. Mangia, she would urge. I knew what this meant, because I had just started taking French lessons.

There was nothing cosmopolitan about my encounters with Mrs Frascati. She and her kitchen and her dishes were all fascinating, certainly, but they also made me uncomfortable. They were simply too unusual. I might, in a few years, be complaining about the homogeneity of life in the Holy Square Mile, but as a boy I was acclimatized, and all but addicted, to it. For her part, Mrs Frascati was untroubled about being unusual: she was simply being Italian. Her house might be in America, but, inside it, she could behave normally — as an Italian woman who was married to a doctor and the mother of three children, and only just the littlest bit plump. I can imagine, now, what she made of us, Americans, but all I remember is a slightly challenging disapproval.

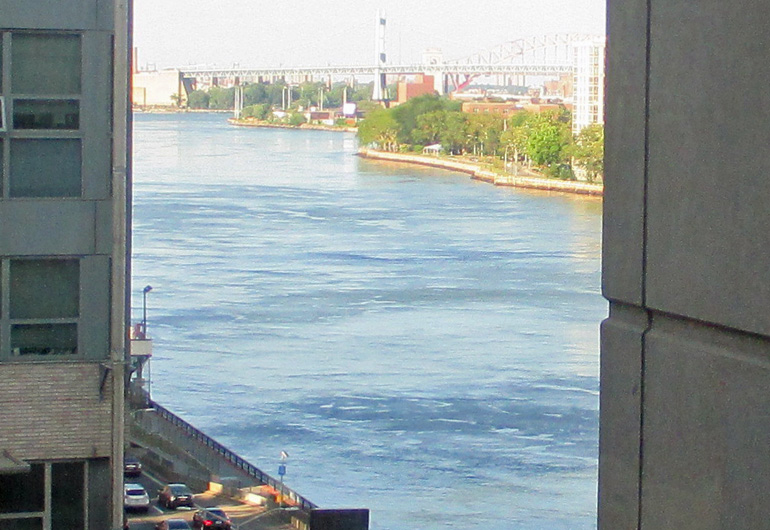

The only thing that I recall clearly about Mrs Frascati, the only non-reducible memory that penetrates the haze of impressions is the Italian lesson. As it happened, Dr Frascati, like my father, was a member of the New York Athletic Club, which operated a sprawling outpost at a place called Traverse Island, on Long Island Sound. It was here that I saw Tony in the last days of our friendship. My family had moved to the house on Paddington Circle that put us, finally, in just plain Bronxville. I had hooked up with a sullen, “intellectual” cluster of disaffected kids, much too brainy and tragic for anything like friendship. Tony, meanwhile, was zooming along on the hormonal highway that bore him aloft even before the visible onset of puberty. He was crazy about the girls, and the girls were crazy about him — although this mutual attraction was confined to terms of mockery and abuse. All that remained of our friendship were two extinct volcanoes, on which we had both turned our backs.

I decided to teach myself Italian. I bought a book (because books are all that there were), and the book taught me that the word for “I” was io. Being too clever by half, I decided that the “i” in io functioned as a “y,” or as a “j” would, if Italian had that letter. One afternoon, finding myself standing by the Olympic salt-water pool at Traverse Island while Tony showed off on the high diving board, I announced to Mrs Frascati, who was lounging on a nearby deck chair, that I was learning her language. Oh yes? Say something. Instead of saying something useful or interesting, I went for clever. “Yo!” I said. What is that? What is that supposed to mean? I explained. Mrs Frascati’s exasperation with Americans finally blew its lid. “Eeeee-aw. Eeeee-aw. Don’t give me Spanish! You don’t know anything about Italy!”

It took a while to understand that Mrs Frascati had, in that outburst, taught me all about it.

***

Jimmy Chapman was a lanky but athletic boy who happened to be almost as fond of talking (when adults weren’t around) as I was. While Tony was a year older, Jimmy was a year younger, and we all went to different schools. And while I remember meeting Tony for the first time, playing in the street between our houses, I don’t remember not knowing Jimmy. The Chapmans and my parents were friends. Perhaps it would be better to say that my parents really liked Jimmy’s father, Roy Chapman, a lot, and put up with his mother, Jeanne Chapman, when they had to. Even though I have invented names for the Frascatis and the Chapmans, I still hesitate to say that Jeanne Chapman had a drinking problem. That isn’t how it was put. It wasn’t put; but I have an obstinate recollection of hearing one of my parents mutter, with no little disgust, that Jeanne Chapman was a drunk.

My mother, who was not keen on Italians, decided that I would be improved by a friendship with Jimmy Chapman, and a series of playdates and sleepovers was arranged. I don’t remember having a bad time with Jimmy — we had a lot of fun, as kids still did in those days, abusing the telephone. Jimmy knew a lot of dirty jokes, and I remember three of them, although one of them I never quite understood (and, when understanding began to dawn, I pulled down the shade). He would draw a picture of a light bulb and then tell me that it was his teacher, bending over to put on her girdle. It did not take forever for our fountains of loquacity to dry up, but we had fun while it lasted. I always had the impression that Jimmy would much rather have been playing baseball. Looking back, I think that he would have been happier had we been tossing a baseball back and forth while we joked, with maybe some pointless running around. I’ve never been able to decide whether my inability to catch a ball was an inborn ineptitude or the result of an absolute lack of interest.

Whenever Jimmy and I got together for a sleepover — a highly domesticated form of camping out for one child at a time — we prattled like monkeys into the small hours. I don’t remember being reprimanded at my house; perhaps I was a better enforcer of whispering. At Jimmy’s, however, we made such a racket one night that Roy Chapman got pissed off and stormed down the hall to tell us to shut the hell up. It wasn’t what he said that shocked me.

The middle-aged men that I knew — from such places as the locker room at Traverse Island — never ever ever looked like the Greek statues in museums, and not just because they were no longer young. These were prosperous executives, avid golfers perhaps but, at a time when gyms were patronized by cultish bodybuilders only, always pudgy around the middle. (Tennis players, in contrast, were too skinny to be mistaken for those statues.) But Roy Chapman, appearing suddenly in the doorway to Jimmy’s room, stark naked, furred chest only faintly grizzled, hands gripping the jambs, was a god, all six-six-plus of him. I couldn’t have made the comparison at the time, and Roy Chapman didn’t have a beard, but he was the very image of a bronze Poseidon, dredged from the Mediterranean, only livelier. His nakedness, far from suggesting vulnerability, blazed with the threat of terrible powers that he might unleash upon us.

Having barked, he disappeared. We quieted down.

This apparition might have been even more upsetting had it occurred in a normal Bronxville house. The Chapman’s house was not normal. There was nothing Colonial or Tudor about it. It didn’t seem to have any style at all, because it was hidden away behind a forest of rhododendrons. There was a small circular gravel driveway, where Roy Chapman parked his 1954 Buick. Owning a 1954 Buick in 1958 or 1959 was not normal, either. My father bought a new car every other year, and after he inherited his mother’s Dodge and we became a two-car family, there was a new car in the garage every year. That was normal. Roy Chapman, much ribbed about his ancient jalopy, claimed that he could not fit his giant’s frame into newer cars. And I’m sure that, when he did so, he spoke with enough Neptunian vigor to put a stop to the comments. Beyond the car, there were steps to a porch and the front door — all that could be seen from the street.

I usually came in through the kitchen, at the back of the house. I remember two things about the kitchen. There was a KitchenAid stand mixer on a counter. I had never seen such an impressive piece of equipment in a kitchen before, and I would have immediately pegged my family as less prosperous if it had not been for the other thing, which was a palpable neglect. Was the kitchen dirty? Probably not — but I wasn’t disposed to look too closely. Whether or not Jeanne Chapman ever made us a sandwich, my recollection of her kitchen is the negative of Mrs Frascati’s. I don’t even recall a table, much less sitting down to a lot of food. I must have been busy not remembering.

If you entered the Chapman’s house by the front door, there was a living room to the right. We were not allowed to enter it, which, since it led nowhere, was no inconvenience. From time to time, Jeanne Chapman’s French mother, who was called something like “Woo-Hoo,” and who was also, if not demented, then permanently out to lunch, would drift in and out; and there was one time when Jeanne Chapman sat down at the grand piano and played a song that I had never heard of: “Mood Indigo.” She asked me if I liked the song, but let’s face it: “Mood Indigo” is so sophisticated that I wasn’t even aware of a melody. What on earth did “mood indigo” even mean? It wasn’t a song; it was a state of mind.

If you turned from the hallway to the left, you could walk through to an octagonal room with window seats all round (except for the sides that abutted the rest of the house). While the living room was furnished with something approaching elegance (but still dogged by neglect), the octagonal room, which may have been called the TV room or the tower room (above the master bedroom overhead, there rose a squat Victorian turret), was not decorated at all. There were ratty upholstered chairs, and a sofa no doubt, along with other playroom bric-à-brac, and the television. The television was always tuned in to a game of some kind. Roy Chapman was spoken of as an athlete by my parents, and he had a keen interest in sports. So did Jimmy. I’d have been bored to death, but I was saved, transported, redeemed by a wonderful discovery on the window seat — and a discovery it was, because my parents were little old ladies from Dubuque who had no interest in subscribing to the magazine.

The New Yorker Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Album.

So there it was, in a house that might have been drawn by Charles Addams, whose heavy-lidded mistress might have stepped out of a cartoon by Richard Taylor, whose master’s casual nudity would have been right at home in the work of artists ranging from Peter Arno to William Steig, that I page by page woke up to the world.